Note:

As we start the second decade of A Short Distance Ahead, this week’s essay will look back at the influence that science-fiction had upon AI’s early pioneers.

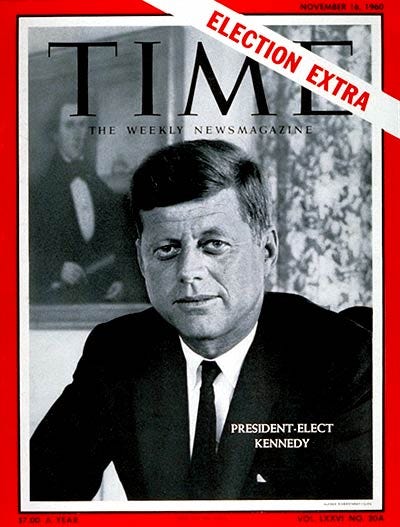

The year was 1960, and the world was changing at a dizzying pace. As John F. Kennedy clinched the presidency in the first-ever televised debates, showcasing the growing power of the small screen,1 other forces were reshaping the global landscape. The U-2 spy plane incident strained Cold War tensions to the breaking point,2 while in China, Mao's Great Leap Forward was descending into a catastrophic famine.3 Meanwhile, the formation of OPEC signaled a shift in the balance of global economic power.4

Amidst these geopolitical tremors, another kind of revolution was brewing in the halls of academia and research labs across America. Here, a small group of scientists and mathematicians were busy trying to breathe life into machines, to make them think. As the first TIROS weather satellite beamed images back to Earth,5 giving humanity an unprecedented view of its own atmosphere, these researchers were attempting to create an entirely new kind of atmosphere - one where human and machine intelligence could coexist and collaborate.

In one corner, John McCarthy was refining LISP, a programming language he'd designed to give machines a way to manipulate symbols as deftly as a poet manipulates words. In another, Marvin Minsky was pondering how to make machines learn, his mind a whirlwind of neurons and logic gates. And in a quiet lab in Pittsburgh, two men named Allen Newell and Herbert Simon were teaching a computer to prove mathematical theorems, as if preparing it for some great cosmic exam.

But as these pioneers of artificial intelligence bent over their punch cards and soldering irons, they were driven by more than just the cold logic of mathematics and engineering. They were chasing a dream, a vision of the future that had been planted in their minds a decade earlier, when a young biochemist turned writer had published a book that would shape future minds for decades to come.

“I remember reading the first robot stories and deciding I was going to build them. His stories asked how you could possibly impart common sense to a machine, which is something I have spent my life at.” - Marvin Minsky6

To understand the minds of these AI researchers in 1960, we must look back to 1950, when Isaac Asimov's "I, Robot" first hit the shelves…

In 1950, as the world was still reeling from the aftermath of World War II and the dawning realization of atomic power, Isaac Asimov was busy populating the future with robots. But these weren't the clanking, menacing machines of earlier science fiction. Asimov's robots were thoughtful, ethical beings, bound by three simple but profound laws.

Asimov himself was something of an intellectual machine, churning out ideas and words at a prodigious rate. Born in 1920 in Petrovichi, Russia, he had immigrated to the United States with his family at the age of three. Growing up in Brooklyn, young Isaac devoured books in his family's candy store, teaching himself to read at age five and quickly exhausting the children's section of the local library. By his early teens, he was not just reading, but also writing science fiction, submitting his first story to a magazine at the tender age of fifteen.

A precocious student, Asimov entered Columbia University at fifteen, earning his bachelor's degree in chemistry by nineteen and his PhD by twenty-six. But even as he pursued his scientific education, his mind was filled with visions of the future. He balanced his academic work with a growing career as a science fiction writer, his agile mind moving effortlessly between the rigors of biochemistry and the boundless possibilities of speculative fiction. It was this unique combination of scientific knowledge and imaginative prowess that allowed him to create robots that were not just believable, but philosophically compelling. His Three Laws of Robotics,7 which would become the cornerstone of his robot stories, were:

A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Laws.

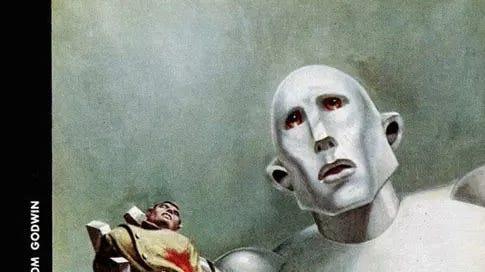

These laws weren't dreamed up overnight. They were the result of years of thought and writing, dating back to 1939 when a young Asimov, then just nineteen, had begun visiting John W. Campbell, the legendary editor of Astounding Science Fiction.8 Campbell was a larger-than-life figure with a mind like a supernova, and a background as colorful as the stories he published.

Born in Newark, New Jersey, Campbell had a checkered academic career, flunking out of M.I.T. before eventually earning a physics degree from Duke University in 1934. He had weathered the early years of the Depression by juggling various jobs, including technical writing and penning science fiction novels. As editor of Astounding, Campbell was steering science fiction away from simplistic 'space operas' towards more sophisticated tales exploring sociology, psychology, and philosophy. His vision would usher in what many consider "the Golden Age" of science fiction. However, this Golden Age, like much of the scientific and literary world then, was predominantly shaped by male voices and often reflected controversial societal views of the time, perspectives that couldn’t help but influence the nascent field of AI research.

“Campbell had wanted to be an inventor or scientist, and when he found himself working as an editor instead, he redefined the pulps as a laboratory for ideas—improving the writing, developing talent, and handing out entire plots for stories. America’s future, by definition, was unknown, with a rate of change that would only increase. To prepare for this coming acceleration, he turned science fiction from a literature of escapism into a machine for generating analogies...” 9

Campbell would spend hours discussing story ideas with the young Asimov, their conversations a crucible where the future of science fiction was being forged. It was during one of these sessions that Campbell challenged Asimov to write a robot story that didn't follow the tired old trope of robots rebelling against their creators. Asimov rose to the challenge, and in doing so, he created a new vision of human-machine interaction, one based on cooperation and ethical behavior rather than conflict.

The Three Laws first appeared in Asimov's 1942 story "Runaround," but it was in the 1950 collection "I, Robot" that they truly came into their own. Through a series of interconnected stories, Asimov explored the implications of these laws, creating a future history of robotics that was both scientifically plausible and philosophically profound.

Now, a decade later, Asimov's vision had permeated the nascent field of artificial intelligence. Marvin Minsky, who would later recall deciding to build robots after reading Asimov's stories, was now grappling with the real-world challenges of creating machine intelligence. John McCarthy, in developing his Advice Taker concept, was in essence trying to create a system that could reason ethically, much like Asimov's robots.

Even those who weren't directly inspired by Asimov found themselves working in a field shaped by his ideas. The notion that intelligent machines could be not just useful tools but ethical actors in their own right was no longer merely science fiction—it was a research goal.

That year, J.C.R. Licklider, a psychologist and computer scientist at MIT, published his seminal paper "Man-Computer Symbiosis,"10 envisioning a future where humans and computers would work together in intimate association. Licklider11 would later play a crucial role in the development of ARPANET (the precursor to the internet). His paper proposed a partnership between human brains and computing machines, each complementing the other's strengths. His ideas were revolutionary at a time when computers were still seen as giant calculators, suggesting instead that they could become interactive tools for thinking and decision-making. Licklider's vision, much like Asimov's, would prove prescient, pointing the way towards a future where the boundaries between human and artificial intelligence would become ever more porous.

And so, as 1960 unfolded, with its promise of space exploration and its undercurrent of Cold War tension, the AI researchers continued their work. They were, in a very real sense, trying to bridge the gap between Asimov's fiction and scientific fact. And while they hadn't yet created a positronic brain or a robot governed by the Three Laws, they were laying the groundwork for a future where the line between human and machine intelligence would become increasingly blurred.

How Astounding Science Fiction Saw the Future (gift article)

The Dream Machine by M. Mitchell Waldrop