The year was 1957, and the world of artificial intelligence stood on the cusp of transformation. Just a year before, the lawns of Dartmouth College had echoed with the excitement of the now-famous conference that many consider the birthplace of AI as a field of research. Among the work presented at Dartmouth, it was Herbert A. Simon and Allen Newell’s Logic Theorist that proved to be the most notable, although for the most part, it failed to capture the imaginations or attention of the other attendees.1

Simon was not a mathematician, but a political scientist, and was interested in how “organizations could enhance rational decision-making. Artificial systems, he believed, could help people make more sensible choices.” But Simon also “thought there was something fundamentally similar between human minds and computers, in that he viewed them both as information-processing systems.” He met Newell, a psychologist and computer scientist while working at the RAND Corporation, a curious blend of military think tank and scientific playground, which was where they developed The Logic Theorist, a program that could prove mathematical theorems with a ghostly echo of human reasoning.2

As the summer at Dartmouth receded, Simon and Newell found themselves in a whirlwind of activity at Carnegie Institute of Technology (later to become Carnegie Mellon University), as they were instrumental in founding what would become the first, and one of the most influential AI labs in the world, nestled within the university's Computation Center. The lab hummed with potential, like a computer warming up for a complex calculation.3

The intellectual establishment of the 1950s, by and large, preferred to believe that “a machine can never do X.” AI researchers naturally responded by demonstrating one X after another . . . John McCarthy referred to this period as the “Look, Ma, no hands!” era. 4

Meanwhile, at Bell Labs in New Jersey, Mohamed Atalla, an Egyptian-American engineer and physicist, was perfecting a way to make silicon behave, which would eventually lead to computers small enough to fit in a pocket. And Atalla's work on silicon oxide surface passivation was like teaching sand to think, and it would become the foundation for the modern computer age, though at the time it just looked like a very shiny, very flat rock.5

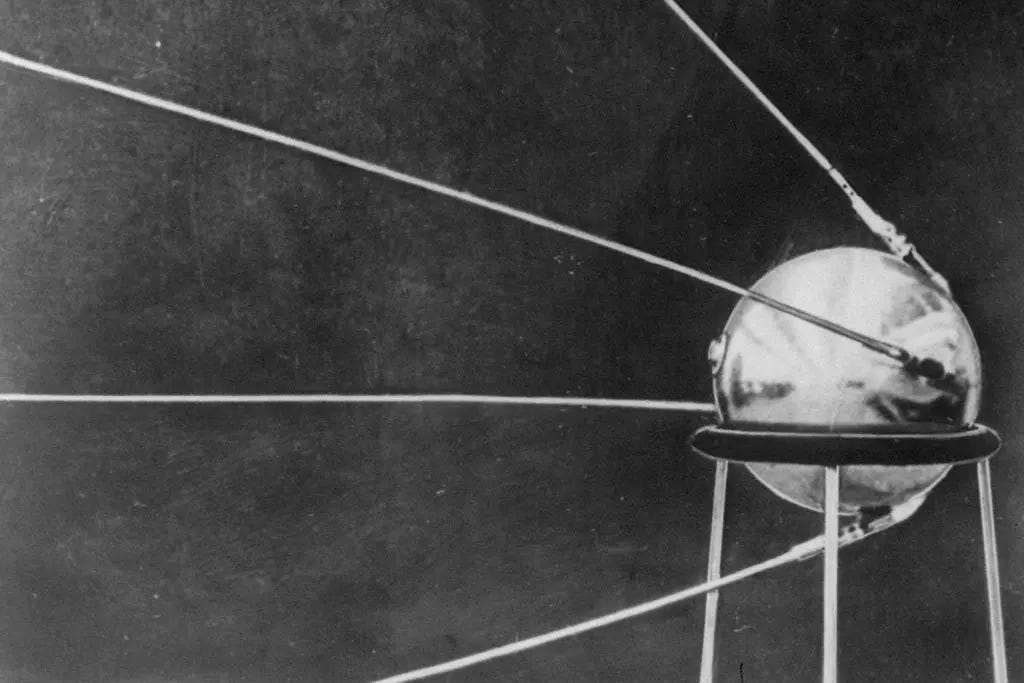

And as Atalla coaxed silicon into submission, the Soviets were busy launching Sputnik 1, a shiny ball that became the first human-made object put into space. And as the artificial satellite beeped its way around the Earth it officially kicked off the “Space Race,” and made Americans very nervous. But perhaps not as nervous as when the Soviets’ successfully tested their first intercontinental ballistic missile a few months later, which made Americans even more nervous, and some started building bomb shelters in their backyards next to their barbecue pits.6 7

All this nervousness about bombs and space didn't stop scientists from 67 countries from working together on the International Geophysical Year, proving that when it came to studying the Earth, people could cooperate almost as well as they could compete.8

While scientists were measuring the Earth, Ghana was measuring its newfound independence, becoming the first sub-Saharan African country to shake off colonial rule.9 And it changed its name from the Gold Coast, because gold was no longer as important as freedom. And Martin Luther King Jr. went to the independence ceremony and met the new Prime Minister Kwame Nkrumah who wore his prison cap to the ceremony to show that freedom isn't free. And King cried with joy even though it wasn't his country becoming free, and while he was there he also met Richard Nixon, who was the Vice President of America at the time, and invited him to visit Alabama where black people were fighting for freedom just like in Ghana, but Nixon didn’t seem very interested.10

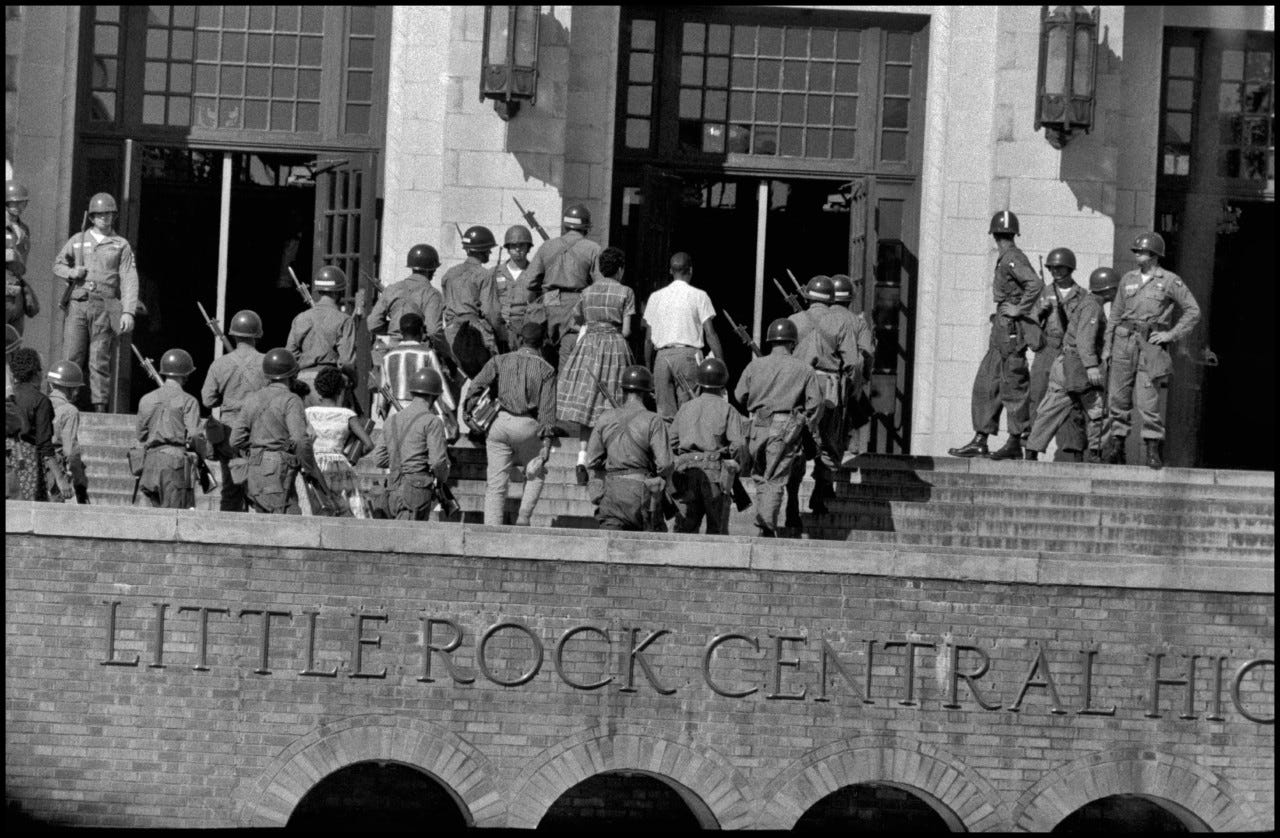

And a few months later nine black students in Little Rock, Arkansas, tried to go to school, which shouldn't have been news but was. And the president had to send in the army to protect them, because apparently some people thought education was more dangerous than tanks.11

And meanwhile, Jack Kerouac wrote a book about driving around America and taking drugs and not having a job and many young people thought this sounded like a good idea although their parents tended to disagree.12

And in Rome, six European countries signed a treaty to create the European Economic Community because they thought trading with each other might be nicer than having wars and some people said this was the beginning of a new era of peace and prosperity while others said it was just a clever way for politicians to have fancy dinners in Brussels.13

And China launched its Anti-Rightist campaign, a stark reversal of the brief period of openness that had preceded it. When Mao had said "let a hundred flowers bloom," many had taken him at his word, only to discover that dissent was a dangerous crop to cultivate. The campaign swept through the country like a chill wind, and intellectuals who had spoken out during the Hundred Flowers Campaign found themselves suddenly uprooted. They were sent to "re-education camps," a euphemism for places where free thought went to wither, and where the curriculum consisted mainly of hard labor and political indoctrination. It was a harsh reminder that in some gardens, uniformity was prized above diversity, and that the price of speaking out could be devastatingly high.14

As 1957 drew to a close, the world had become a place where machines were learning to think, rocks were turning into computers, and a small metal ball circling the Earth could change the course of history.

And the year 1958 was just around the corner.