The year was 1958 and the energy of discovery was swirling inside a small number of AI laboratories at universities like MIT and Carnegie Mellon, as well as within research departments at organizations like IBM and RAND. The swirls of energy were shaped by a contrasting mix of ideas and characters, with each side convinced they were on the verge of teaching machines to think, even though they couldn't quite agree on what thinking was.

John McCarthy, the organizer of the Dartmouth conference, spent the year juggling two groundbreaking ideas while bouncing between the IBM Information Research Department in Poughkeepsie, New York and joining the faculty at MIT, where he started the Artificial Intelligence Project with his friend, Marvin Minsky. This project, generously supported by the M.I.T. Research Laboratory of Electronics under a flexible armed services contract, gave McCarthy the freedom to pursue his scientific interests.

McCarthy’s first idea was called the Advice Taker, a hypothetical program that could use common sense to solve problems. McCarthy imagined it planning a trip to the airport simply by thinking logically about the world. More ambitiously, it was supposed to learn new things without reprogramming, much like a child absorbing facts about the world. While the Advice Taker never materialized, its concept profoundly influenced AI thinking for years to come, shaping how researchers approached the challenge of creating machines that could truly think and learn.1

His second idea was a programming language called LISP - officially short for LISt Processing, though some wryly suggested it meant Lots of Irritating Superfluous Parentheses. McCarthy's vision was to represent knowledge as lists and give machines a way to manipulate these lists, believing this was the path to artificial intelligence. LISP allowed programmers to treat code as data and data as code, essentially teaching a book to rewrite itself as you read it.

“McCarthy published a remarkable paper in which he did for programming something like what Euclid did for geometry. He showed how, given a handful of simple operators and a notation for functions, you can build a whole programming language.” 2

Meanwhile, a research psychologist and project engineer at the Cornell Aeronautical Laboratory in Buffalo, New York named, Frank Rosenblatt was taking a different approach to creating thinking machines. He created something called the Perceptron, which was inspired by the way neurons work in the brain. The Perceptron could learn to recognize patterns, a bit like how a child learns to recognize a cat or a dog. Rosenblatt's machine didn't need to be programmed with rules about what made a cat a cat; it could figure it out on its own, given enough examples. This was also very exciting to some people and very confusing to others, which is still often the case with important ideas.3

McCarthy's LISP and Rosenblatt's Perceptron represented two different paths in the quest for artificial intelligence. One path said that intelligence was about manipulating symbols and following logical rules, like a very complex game of chess. The other path said that intelligence was about learning from experience and recognizing patterns, like a very complex game of "guess what I'm thinking of." Both paths would lead to important discoveries, and both paths would lead to dead ends, because the human mind turned out to be more complex than either chess or guessing games.

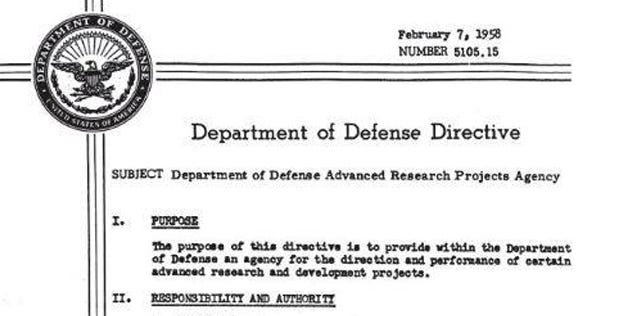

And as the field of AI research was growing, the United States government was growing more anxious, spurred by the shock of Sputnik and the fear of falling behind in the Cold War, they decided that the best defense was a good offense — or at least, a well-funded one. This belief manifested in the creation of two new agencies, aimed at propelling America to the forefront of scientific and technological advancement.

First came DARPA, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, born out of America's space-age insecurities and a burning desire to have cooler gadgets than the Soviets. DARPA was given the lofty goal of making sure the U.S. would never again be surprised by technological advances from other nations, which was a bit like trying to predict the future without a crystal ball, and many would say in trying to build a better weapon, they accidentally invented the future.4

Not to be outdone, the government quickly followed up with NASA, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. If DARPA was about keeping secrets, NASA was about making headlines. Its mission was to boldly go where no American had gone before, preferably before any Soviet got there first. But NASA quickly discovered that space was more complicated than anyone had imagined, when James Van Allen found two doughnut-shaped regions of charged particles trapped in Earth's magnetic field. These Van Allen belts, as they came to be called, were like nature's own force field around the planet, and suddenly the dream of space travel seemed both more difficult and more necessary.56

And so, in the span of a few months, the United States had sprouted two new branches on its governmental tree, each tasked with reaching for the stars in its own way. DARPA would do it secretly, NASA would do it with cameras rolling, and both would do it with enough acronyms to make even the most alphabet-soup-loving bureaucrat's head spin.

Meanwhile, as some humans were looking up at the stars, others were looking down at tiny pieces of silicon. A man named Jack Kilby was sitting in an empty lab at Texas Instruments, because everyone else was on vacation, and he was new and didn't have any vacation days. So he decided to solve the problem of making electronics smaller by putting all the parts on a single piece of semiconductor material. He called it an integrated circuit, but everyone else eventually called it a microchip.7

And while America was busy creating agencies, the rest of the world was undergoing its own transformations. In France, Charles de Gaulle, a man who had once led the resistance against Nazi occupation, now found himself leading a resistance against political instability. He ushered in the Fifth Republic, a system of government that gave more power to the president, as if France had decided that what it really needed was a stronger dose of authority.8

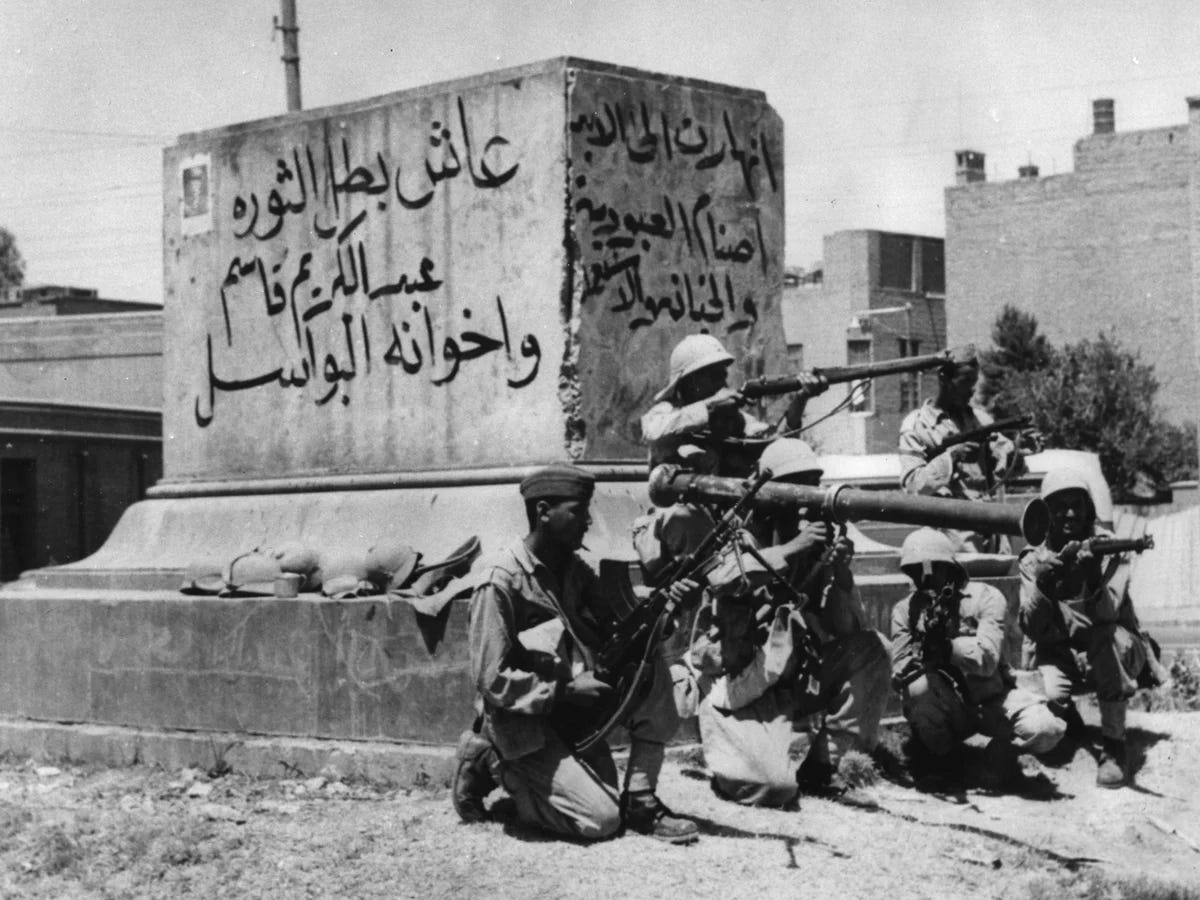

Across the Mediterranean, Iraq was having its own political upheaval. The monarchy that had ruled since the country's independence was overthrown in a coup d'état, replaced by a republic that promised progress and pan-Arab unity. It was a reminder that in some parts of the world, the future arrived not through agencies or education, but through a coup.9

Meanwhile, in China, Mao Zedong launched the Great Leap Forward, an ambitious plan to rapidly transform the country from an agrarian economy into a modern communist society. Communes were established, backyard furnaces were built to produce steel, and grand promises were made about surpassing Western industrial output. It was an attempt to rewrite the rules of economic development, with consequences that would echo for decades to come.10

And the year 1959 was just around the corner.