Welcome to A Short Distance Ahead, a weekly exploration of artificial intelligence’s past to better understand its present, and shape its future. Each essay focuses on a single year, tracing the technological, political, and cultural shifts that helped lay the foundation for today’s AI landscape.

As an experiment, I’m co-writing these essays with AI, despite deep concerns about how algorithmic text might dilute the human spirit of storytelling. But, by engaging directly with these tools, I hope to better understand their influence on creativity, consciousness, and connection. If you find value in this work, please consider sharing it or becoming a subscriber to support the series. As always, I’m grateful for your time and attention.

The year was 1995, and while the internet was going public, a robot was quietly painting in Boston.

In a cavernous hall at The Computer Museum, visitors gathered to witness something curious: an autonomous machine creating original art. AARON, the robotic artist designed by Harold Cohen, moved methodically across large sheets of paper, its mechanical arm reaching for cups of dye, dipping brushes, making decisions about color and composition that no programmer had explicitly coded.

"I write programs. Programs make drawings," Cohen would say, a deceptive simplicity masking twenty-five years of obsession. At 75, the British painter-turned-computer scientist had devoted more than a quarter-century to this peculiar collaboration between carbon and silicon.

"Putting dye on paper is easy: you just build a machine!" Cohen joked about AARON's newly acquired ability to paint in color. But the real challenge had been teaching the machine to think about color, to understand that faces aren't green, that a red sweater demands a differently colored background. To comprehend, in other words, the underlying logic of human perception without simply mimicking human artwork.

The exhibit, which ran from April through May, was a quiet milestone in a year of digital revolutions.1 While the world's attention fixed on IPOs and emerging platforms, AARON posed a quieter, more intimate question, one that rarely appears in IPO prospectuses: What is a machine for?

As Cohen explained to his wife at the time, Becky Cohen, in a conversation that spring: "I suppose I am in the position of being entirely responsible for someone else's education. I go on feeding facts and numbers and positions and opinions and beliefs into this someone, and it turns out finally that I hadn't really put in what I thought I had at all."

This wasn't the language of platforms or protocols. It was the language of pedagogy, of relationship, of dialogue between creator and creation. AARON wasn't infrastructure. It was inquiry.

And almost no one was paying attention.

On August 9, the day of Netscape's initial public offering, its stock was supposed to open at $28 per share. But buyer demand was so overwhelming that trading was delayed. When the first trade finally hit the ticker around 11 AM, the price was $71 – almost triple the offer price. By day's end, the stock settled at $58.25, valuing the company at $2.1 billion.

On the front page the next day, the Wall Street Journal observed, "It took General Dynamics Corp. 43 years to become a corporation worth $2.7 billion... It took Netscape Communications Corp. about a minute."

This was the story of 1995 that would define the digital age: explosive growth, frictionless value creation, instantaneous wealth. Jim Clark, Netscape's billionaire co-founder,2 described this new paradigm: "You didn't build some physical thing, move it down an assembly line, box and shrink-wrap it, and stick it on a store shelf. You conceived of it in your head, produced it in a computer, and tossed it up for grabs on the Net."3

Across Silicon Valley and the Northwest, entrepreneurs were racing to build platforms that would capture the boundless potential of this new digital frontier. In Redmond, Washington, Bill Gates and Steve Ballmer were orchestrating what would become the most significant product launch in Microsoft's history – Windows 95. The operating system, accompanied by a $300 million marketing campaign featuring the Rolling Stones' Start Me Up, would sell 7 million copies in its first five weeks, cementing Microsoft's dominance and bringing graphical computing to mainstream users worldwide. At Sun Microsystems, James Gosling and his team publicly released Java, a revolutionary programming language promising to let developers "write once, run anywhere" across different operating systems and devices – a direct challenge to Microsoft's platform control.

Meanwhile, in San Jose, Pierre Omidyar was coding a simple auction website originally called AuctionWeb (later eBay), where one of the first items sold would be a broken laser pointer for $14.83. In Seattle, Jeff Bezos launched Amazon.com as an online bookstore, dreaming of the day it would sell "everything." These weren't just businesses — they were staking claims to what Gates himself had called "the gold rush."

These were the architects of the commercial internet. The infrastructure builders, the attention merchants, the ecosystem designers. Their vision of the digital future was expansive, ambitious, and deeply American in its emphasis on growth, markets, and individual opportunity.

Other voices were articulating alternative visions for the digital frontier. The Electronic Frontier Foundation, co-founded by John Perry Barlow, was already championing the idea that traditional governments should have limited authority in digital spaces. Cypherpunks were developing encryption tools to protect privacy and enable anonymous digital transactions. Tim Berners-Lee, who had invented the World Wide Web just a few years earlier, continued to advocate for keeping it open, decentralized, and accessible to all. They were united not by infrastructure, but by a shared belief in sovereignty through software, where freedom, not frictionlessness, was the design goal.

These were the champions of a different digital future, one where power was distributed rather than concentrated, where users controlled their data, where freedom and privacy were protected by code rather than law.

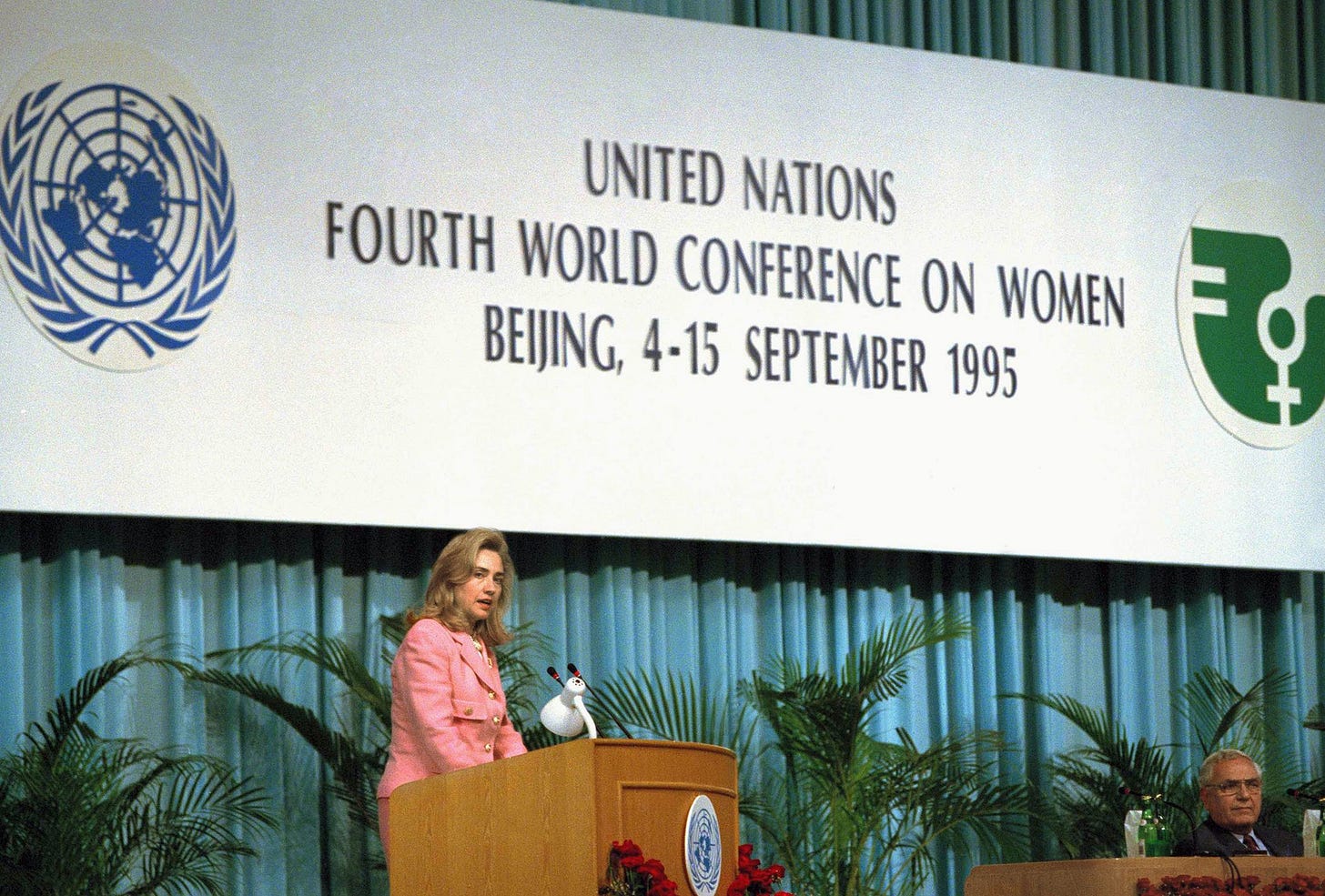

Meanwhile, across the Pacific, China was crafting yet another vision of technology's role. In Beijing that September, the government hosted the Fourth UN World Conference on Women while simultaneously restricting press freedom and relegating the NGO Forum to the outskirts of the city, a symbolic and logistical move that mirrored its discomfort with open civil society participation. The state invested heavily in STEM education and research programs through initiatives like the "863 Program," laying the groundwork for a tech-driven development model where innovation served national rather than individual or corporate interests.

Between these competing futures – commercial, decentralized, state-directed – a robot continued painting in Boston, unnoticed except by museum visitors fascinated by its mechanical arm.

AARON wasn't a third path for the digital future. It was barely a footnote. But in its obscurity lay a profound question about our relationship with machines, one that neither the platform builders nor the decentralizers were asking.

Cohen had never intended AARON to simulate human creativity or replace human artists. "I would like AARON's work to look to the human viewer the way African sculpture must have looked to western artists at the end of the 19th century," he explained. "They knew it was made by people somewhere, but these people were from a different, even alien, culture." He wasn’t engineering intelligence, but cultivating estrangement—inviting us to see the machine’s mind as foreign, yet familiar.

This wasn't a vision of machines as platforms for human activity, nor as tools for human liberation. It was a conception of technology as a fundamentally different kind of intelligence, not competing with human creativity but complementing it, extending it into new domains through an ongoing dialogue between creator and created.

In the Computer Museum's exhibit hall, AARON painted all day, every day. It never tired. It never questioned. It never knew what it was creating, only that it was following the rules Cohen had taught it over their quarter-century partnership. It never worried about whether the paintings would sell, whether critics would dismiss them, whether it would be remembered as a novelty or a pioneer.

It just painted.

While the commercial vision ascended. By December, Netscape's stock would hit $171 a share. The following year, the twenty-four-year-old co-founder Marc Andreessen would grace the cover of TIME magazine, barefoot and grinning beneath the headline "The Golden Geeks." The stock market experienced one of its best years in history, with the Dow Jones Industrial Average soaring 33.45%.

The technological foundations for today's data economy were being established in academic labs. The UCI Machine Learning Repository expanded its datasets, becoming a benchmark for algorithm development. Corinna Cortes and Vladimir Vapnik introduced the Support Vector Machine to a broader audience.4 Richard Wallace developed the chatbot A.L.I.C.E, using handcrafted rules written in a markup language he created called AIML. Inspired by Joseph Weizenbaum’s ELIZA, A.L.I.C.E. became a foundational experiment in conversational AI, offering an early glimpse of how the internet could serve not only as a stage for human-machine dialogue, but as a participatory testing ground for interactive systems.5

While these developments gathered little public attention, they represented a shift away from the symbolic, rule-based approach that Cohen had employed with AARON, toward the statistical, data-driven paradigm that would eventually dominate AI research. Unlike AARON, which relied on hand-coded rules and symbolic logic to model perception and artistic reasoning, these new approaches learned patterns statistically from large datasets.

Support Vector Machines, marked a turning point: rather than teaching a machine how to think, engineers were beginning to train machines to discover how we think—by digesting enough examples. It was a shift from dialogue to prediction, from epistemology to probability. Rather than encoding understanding, these systems inferred patterns, trading introspection for accuracy.

In November, Pixar released Toy Story, the first feature-length film made entirely with computer-generated imagery.6 It grossed $373 million worldwide and instantly changed animation. The traditional techniques that had defined the medium since Snow White seemed suddenly obsolete.

Just weeks later, Pixar went public. The IPO was a resounding success, echoing Netscape’s debut earlier that summer. Digital imagination—once the domain of artists and technologists—was now a market force, a Wall Street asset.

The film's plot followed traditional cloth cowboy doll Woody as he dealt with his young owner Andy's affections being usurped by the shiny plastic spaceman Buzz Lightyear – a narrative that mirrored the broader cultural transition from analog to digital, from handcraft to automation, from the patient accumulation of skill to the instantaneous creation of value.

But the story's conclusion, with both toys finding their place in Andy's world, suggested a more nuanced relationship between old and new technologies than the winner-take-all mentality of Silicon Valley.

A choice had been made, though few recognized it at the time. The digital future would be built around platforms and scale, attention and extraction. The introspective, collaborative approach embodied by AARON – the patient, decades-long conversation between artist and machine — would remain largely unexplored.

During one of the interviews conducted at the Computer Museum exhibition, Cohen was asked whether he was ever surprised by AARON's creations.

"Of course, I know exactly what AARON knows," he replied, "but I can still be surprised. When you work on a program as I've worked on AARON, you make the program the heir to some subset of your own knowledge. When it plays that knowledge back to you, you can find yourself saying, 'Hey, where did that come from? I didn't realize that that is what I believe.'"

In this observation lay a fundamentally different way of thinking about technology, not as a tool for achieving predefined ends, but as a mirror that reveals ourselves back to us in unexpected ways. Not as infrastructure for commerce or communication, but as a collaborator in understanding.

Cohen returned to his lab to continue refining his program, teaching AARON new rules, new techniques. Outside, the world was changing at an accelerating pace. Everything was becoming code. Everything was becoming digital. Everything was learning to see in color.

"I've never tried to simulate my own work," Cohen insisted, "but whenever I find myself faced with a problem about how the program should proceed, I've asked myself how I would proceed."

The world was building tools for connection—faster, broader, frictionless. But AARON offered something slower, more intimate: a connection not across networks, but between minds: one human, one machine, shaped by years of dialogue.

As 1995 drew to a close, markets raced toward connection at scale, while the deeper questions of what we were connecting to, and why, remained largely unasked.

Three From Today

First from

’s , Merchant presents a guest post written by Mike Pearl at , titled:The original slop: How capitalism degraded art 400 years before AI

Pearl’s essay draws a direct line between the degradation of chintz, a hand-dyed Indian textile art, and the rise of AI-generated imagery today. Just as capital once sanded down the artistry of chintz to mass-produce its surface appearance, generative AI now strips beloved aesthetics (like Studio Ghibli’s) into memeable, soulless shells—flattening visual culture at speed. Pearl suggests that, what took centuries to erode by hand, AI can vaporize in a viral week.

Second, and related to the post above,

recently reflected on a thoughtful response to one of his posts titled, Welcome to the Semantic Apocalypse, about “how AI’s surplus of slop art is draining meaning from culture, went viral and triggered a number of reactions and commentary pieces.” The response to Hoel’s post came from Scott Alexander the writer of mentioned in last week’s “Two From Today.” I appreciated how Hoel shared the critique of his own post, and his response you can read by clicking below:Third, last week, I shared AI 2027, a provocative scenario forecasting rapid and potentially catastrophic AI developments by late 2027. This week, I felt compelled to share an insightful response from Max Tegmark’s Less Wrong, that both appreciates and critiques AI 2027, emphasizing the chaos, geopolitical complexity, and human unpredictability that could significantly affect AI timelines and outcomes. Highly recommended for another, possibly more nuanced perspective on how things might realistically unfold:

Clark was the subject of Michael Lewis’s book The New New Thing, that showed how the modern digital economy was built not on careful planning but on a kind of magnificent recklessness, where being first mattered more than being right. It still holds up as a both a historical document and fable, and wonderfully captures that peculiar Silicon Valley alchemy where visionary obsession meets venture capital, creating not just companies but entirely new industries.

How the Internet Happened: From Netscape to the iPhone by Brian McCullough, 2018

Support Vector Networks, Machine Learning, Vol. 20, Issue 3, 1995 (abstract)

Approximating Life, New York Times Magazine, July 2002 on Richard Wallace (gift)