Welcome to A Short Distance Ahead where we explore artificial intelligence’s past in an attempt to better understand the present and future. In each essay, I'm examining a singular year’s historic milestones and digital turning points, tracing how these technological, political, and cultural shifts laid groundwork for today's AI landscape. As an experiment, I've chosen to co-write these essays with AI, despite deep concerns about how algorithmically-generated text might dilute the uniquely human essence of storytelling. I engage directly with these tools to better understand—and thoughtfully critique—their potential impacts on creativity, consciousness, and human connection. If you find value in these historical explorations, please consider sharing with others who might appreciate them, or by becoming a paid subscriber to support this work. As always, I'm grateful for your time and attention.

The year was 1994, and reality was beginning to dissolve.

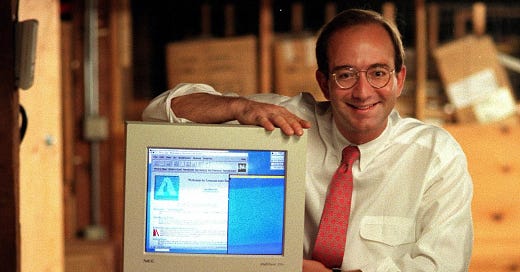

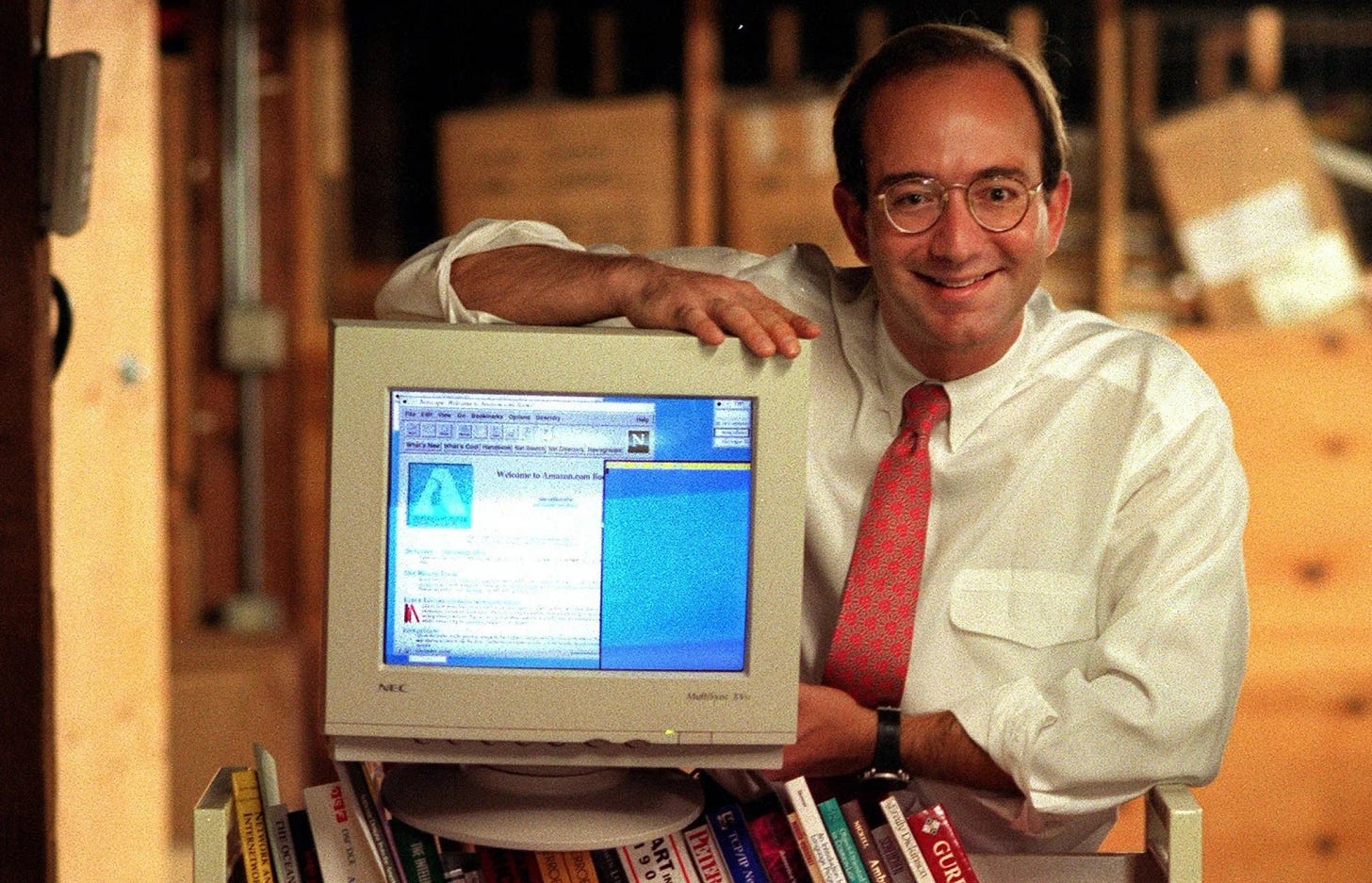

In a small, unremarkable garage in Seattle, a former Wall Street analyst named Jeff Bezos was typing words into a computer, creating a company he initially called "Cadabra." The name evoked magic—abracadabra—and magic it would be, though not the kind that pulls rabbits from hats. This was a different sort of conjuring: the transformation of the tangible world into something weightless, frictionless, invisible.

You could buy a book without touching it first, without smelling its pages or feeling its weight in your hands. The book would materialize later, as if summoned by incantation rather than purchased. Bezos, explaining his vision to his father in the hopes of convincing his father to invest in his idea, faced a question that sounds comical in retrospect but captured the moment perfectly; Bezos Sr. asked: "What's the internet?"

Meanwhile, in Tokyo, engineers at Sony were finalizing something called the PlayStation. Not the first gaming console, certainly, but one that would forever alter how humans interacted with simulated worlds. Space Invaders had taught us to shoot at blocky aliens; now we could drive racing cars and feel the curves, fire weapons and watch the realistic impact, kick balls into nets with a precision that mimicked physics itself. Reality, but not quite real. Reality+. Or perhaps Reality−. Reality transformed.

In California, two Stanford students were compiling a list of websites, a "directory" they called "Jerry and David's Guide to the World Wide Web," soon to be renamed "Yahoo!" The exclamation mark wasn't ironic — it was genuinely how people felt about finding things online in 1994. Yahoo! was navigating the invisible. Mapping nothing. Organizing emptiness. For the first time, humans could move through a space that existed everywhere and nowhere simultaneously.

And in April, the American Association for Artificial Intelligence was holding a meeting at the suggestion of Steve Cross and Gio Wiederhold, hoping to define an agenda for foundational AI research. Their report revealed a field at a curious inflection point—ubiquitous in vision but limited in practice. Computers were everywhere, but still rigid, unadaptable, entirely dependent on explicit programming. They dreamed of "intelligent simulation systems" and "robot teams," but these remained largely theoretical. Like a child who has learned to crawl but not walk, AI was capable yet constrained, full of potential energy that had not yet become kinetic.

In this moment, Tom Gruber, a Silicon Valley technologist immersed in the newly-birthed World Wide Web, was developing something called Hypermail—software that would transform how groups communicated by creating "a living memory of all our exchanges." Email conversations would no longer exist only in individual inboxes but would become collective, retrievable, permanent. Like Berners-Lee before him, who had untethered text from its linear constraints, Gruber was liberating conversation from its traditional bonds. Communication was becoming hypertext; memory was becoming external.

These were not isolated events. They were manifestations of a deeper transformation—a fundamental shift in how humans experienced their relationship with the physical world. The digital revolution wasn't just making things more convenient; it was dematerializing reality itself.

Consider what was happening: Amazon made buying books into a process that only became tangible when the package arrived. PlayStation converted driving a car or shooting a penalty into a lifelike experience that was definitely not real. Yahoo! mapped an entity that had no physical dimensions. Hypermail turned conversations into artifacts that could be retrieved but never decayed.

If it feels strange to think about 1994 this way—as a pivotal moment when reality began to dissolve—consider what else was happening around the world.

The Channel Tunnel opened, connecting Britain to continental Europe for the first time since the Ice Age. NAFTA came into force, dissolving economic borders between the United States, Canada, and Mexico. The European Union was still in its nascent stages, reimagining what boundaries between nations could mean.

These weren't coincidences. They were symptoms of the same impulse that drove the digital revolution: an obsession with movement, with dissolving barriers, with creating spaces where things could flow freely.1

This obsession had deep historical roots. The generation creating these technologies had grandparents who had fought and died to defend or move borders. Their parents had grown up under the threat of nuclear annihilation, divided by an Iron Curtain. They had witnessed the fall of the Berlin Wall just five years earlier, in 1989. The lesson they took from the 20th century was clear: static systems degenerate; movement is salvation.2

The digital revolution was their answer—an antidote to the poison of immobility. Every innovation shared the same DNA: skipping steps, seeking direct contact, eliminating friction.

And amid these grand transformations, smaller moments captured the tension of this transition. The Mexican Peso Crisis erupted, a reminder that financial systems—increasingly digital and abstract—could still collapse with very real consequences. In Rwanda, approximately 800,000 Tutsi and moderate Hutu were killed in one of the darkest chapters of modern history, showing that ancient hatreds could coexist with newfound connectedness. Kurt Cobain's suicide marked a symbolic end to an era in music and youth culture, just as "Friends" premiered on television, creating a fictional universe where six attractive people navigated life with minimal references to the larger world's complexity.

In artificial intelligence labs, researchers were beginning to pivot from rules to data, from explicit programming to learning. The field of data mining was transitioning from academia to industry, with algorithms like association rule mining and classification trees gaining prominence. These weren't the dramatic breakthroughs that would revolutionize AI years later, but they were signs of a shift: from telling computers what to do to showing them examples and letting them learn.3

And in one of those labs, a young summer intern named Elon Musk was working at Pinnacle Research Institute, studying supercapacitors that might power electric cars and space-based weapons. By night, he was solving programming problems at a video game company called Rocket Science, where he cracked a technical challenge that had stumped their senior engineers. But even then, he sensed that video games, despite his passion for them, weren't how he wanted to spend his life. "I wanted to have more impact," he would later say, unaware of just how thoroughly his life would become intertwined with the dematerialization of reality.4

By year's end, as PlayStation units appeared under Christmas trees and Amazon's first book orders were being processed, the transformation was well underway. We were becoming "hyperhumans"— beings freed from linearity, no longer obliged to follow prescribed paths, capable of moving through information spaces in ways that previous generations could barely comprehend.5

What were we escaping from? What were we running toward? In 1994, these questions remained unanswered, but the direction was clear. We were dissolving the boundaries between physical and digital, between here and there, between now and then. We were becoming something new.

Two From Today

Section where I include two current articles that caught my attention amidst the deluge of recent AI related news.

First, from

’sQuick caveat that I to be careful to not gloss over the fact that I believe there are real theories behind Trump’s tariffs, and I believe we make a mistake to write them off as purely nonsensical and “crazy,” but Merchant’s post humorously yet alarmingly suggests the Trump administration's recent tariffs may have been crafted using simplistic AI chatbot formulas.

He connects this troubling scenario to the AI industry's aggressive promotion of Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), highlighting OpenAI's massive $40 billion investment round driven by inflated expectations. Merchant underscores the irony and danger inherent in how AI technologies—widely marketed as revolutionary and powerful—are actually being utilized in haphazard and irresponsible ways by decision-makers. Merchant’s insightful commentary underscores the gap between AI’s marketed promises and its reckless real-world uses, making his newsletter essential reading for understanding AI’s true impact.

Second, Scott Alexander of

introduces AI 2027, which is a scenario Alexander is participating in that is part of the AI Futures Project. AI 2027 is a scenario that represents their best guess about what the coming AI disruption might look like. “It’s informed by trend extrapolations, wargames, expert feedback, experience at OpenAI, and previous forecasting successes.”Alexander begins the post noting how Daniel Kokotajlo first gained attention in 2021 with his eerily accurate predictions about the rapid evolution of AI in his blog post "What 2026 Looks Like." After joining and later dramatically splitting from OpenAI, he founded the AI Futures Project alongside an impressive team including Eli Lifland, Jonas Vollmer, Thomas Larsen, Romeo Dean, and Alexander (of Slate Star Codex fame). Their latest forecast suggests a plausible yet unsettlingly rapid trajectory for AI — by 2027, AI might accelerate its own development, triggering an intelligence explosion surpassing human capabilities by early 2028.

While exact timelines remain speculative—and my own interest has centered more on the nature and implications of AI rather than precise dates—this detailed scenario provides an unusually clear and thoughtful exploration of potential AI futures. The related podcast, hosted by Dwarkesh Patel and featuring Daniel and Scott, is also highly recommended.

For deeper exploration, I also recommend Helen Toner’s Substack and Brian Christian’s "The Alignment Problem", but the AI 2027 scenario uniquely illuminates the dynamics shaping our AI-driven future, making it a standout in current discussions. Read the full scenario and supplementary materials here.

From Data Mining to Knowledge Discovery in Databases - Fayyad, Piatetsky-Shapiro, and Smyth