A Note before we begin. This week's Two from Today section takes a deeper look at TikTok's impact on children, departing from our usual format of sharing only snippets from recent articles, this time I share some personal perspective on this urgent issue. I hope you'll read to the end.

And also, as I write this, Los Angeles is battling devastating fires. While sharing news from LA, I'm mindful of the many communities worldwide facing similar or worse disasters with far less attention. The inequity of disaster coverage weighs heavily, but I feel

’s dispatch, The Conditions of Apocalypse is worth sharing, and of course, ways to help.As always, thank you for your time and attention.

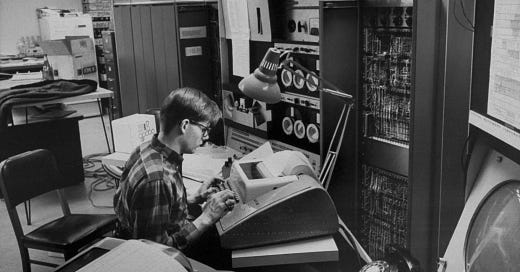

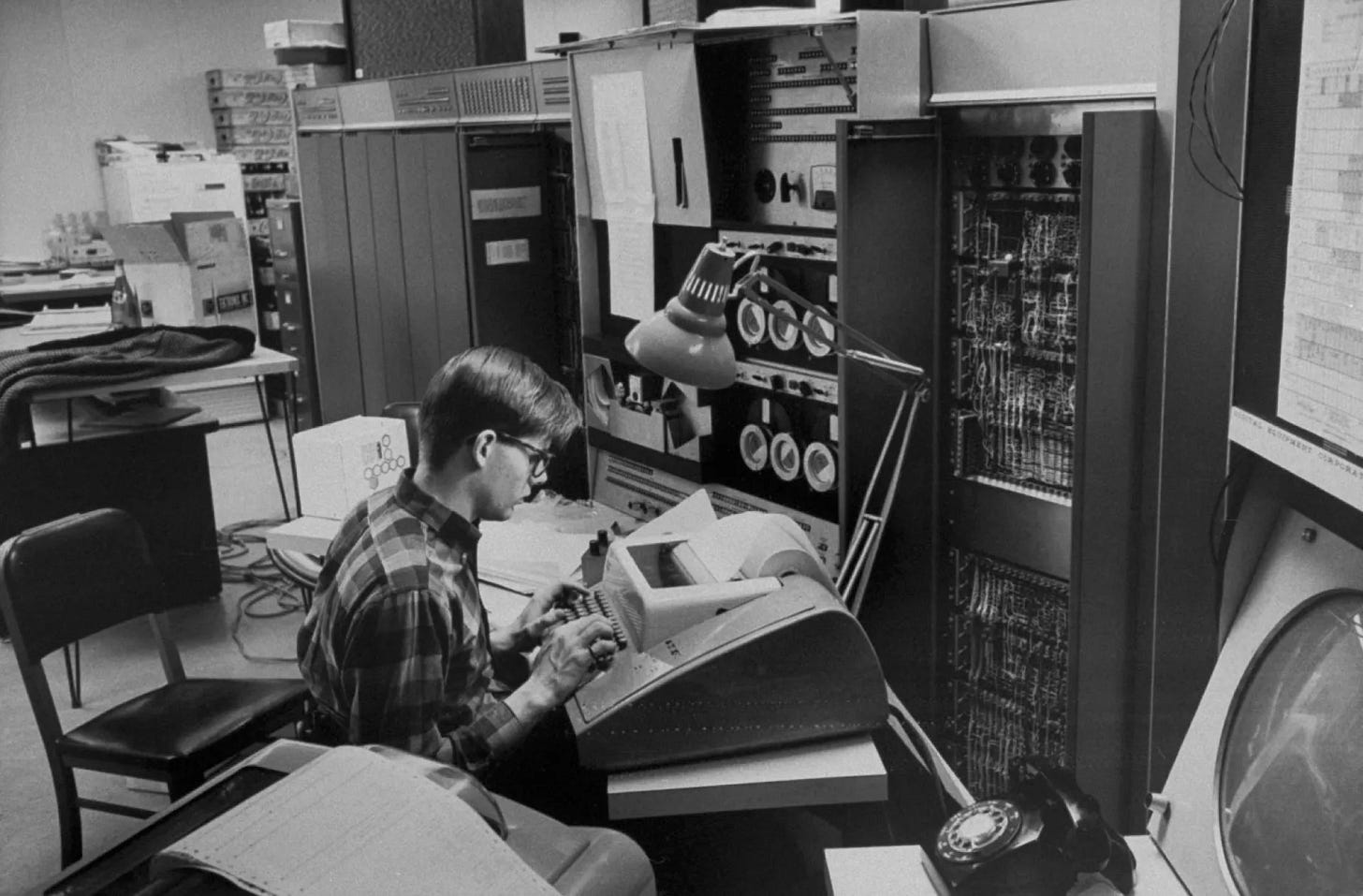

The year was 1982, and in Marvin Minsky's cluttered MIT office, a television murmured news of Israeli forces pushing into Beirut while The New Yorker's Jeremy Bernstein attempted to capture the essence of artificial intelligence's most provocative thinker.1 The scene was quintessential Minsky: computers and musical instruments competing for space, a translucent cube containing an impossible knot perched on a shelf, each object a reflection of his restless, interdisciplinary mind.

Down the hall, students at MIT's Artificial Intelligence Laboratory were turning theoretical questions into practical applications. The field was finding its first commercial applications - expert systems were moving from academic labs to corporate offices. Japan's Fifth Generation Computer Project had ignited a new technological race, and the first AI companies were incorporating. After years of skepticism, money and optimism were flowing back into the field.

But Minsky seemed less interested in these practical applications than in a deeper puzzle. In both his conversations with Bernstein and a piece published that year in AI Magazine, he kept turning the question "Can machines think?" back on his interrogators. The problem, as he saw it, wasn't proving machine intelligence possible - it was understanding why humans were so resistant to the idea. The answer, he suggested, might reveal more about our own limited self-understanding than about the limitations of computers.

As Bernstein explored Minsky's office that year, artificial intelligence was escaping the confines of academic labs in ways both practical and fantastical. In theaters, Disney's Tron was imagining a digital frontier where programs took human form, while in homes across America, the newly released Commodore 64 was making the promise of personal computing tangible for $595. Between these poles of science fiction and consumer reality, something profound was shifting in how humans imagined their relationship with machines.

Minsky, however, was focused on a different kind of escape — not of computers from labs, but of humans from their own assumptions. "Most people are convinced computers cannot think," he wrote in AI Magazine that year.2 "That is, really think." The emphasis on really was pure Minsky — a linguistic trap door opening onto deeper questions. What did we mean by "really" thinking? Did we ourselves understand how we thought well enough to deny that capability to machines?

While Japanese engineers were announcing plans for their Fifth Generation computers and companies like Intellicorp were promising expert systems that could match human specialists in narrow domains, Minsky was suggesting a more radical notion: that our resistance to machine intelligence might be the very key to understanding intelligence itself.

"I don't see any mystery about consciousness," he told Bernstein, characteristically dismissing decades of philosophical hand-wringing. "We just carry around little models of ourselves." But, those implications were unsettling — if consciousness was just self-modeling, couldn't machines do that too? And if they could, what did that say about our own sense of self?

To understand Minsky's preoccupations in 1982 required looking past the immediate commercial promises of artificial intelligence to something more profound. While others worried about solving immediate problems, Minsky saw AI as part of humanity's larger obligation to transcend its limitations. "There's no point to a culture that has only interior goals," he insisted that year, "it becomes more and more selfish and less and less justifiable."

The irony wasn't lost on him. Here he was, in an office filled with machines designed to mimic human thought, suggesting that understanding human consciousness itself might be too "interior" a goal. What mattered was reaching beyond — even if that meant creating entities that might one day surpass us. It was a position that seemed to echo through other realms that year: while physicians were implanting the first permanent artificial heart in a human patient, researchers at Genentech, the first genetic engineering company, an one of the first biotech firms, were producing the first synthetic insulin using genetically engineered bacteria. The boundaries between natural and artificial were blurring across all fields.

Some saw hubris in such ambitions. The same year Minsky was contemplating artificial minds, Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (the future Pope Benedict XVI) warned against technology's overreach. But Minsky took a different view of the divine. Speaking with author Pamela McCorduck that year, he framed AI not as human arrogance but as a kind of sacred duty. Creating thinking machines wasn't about worshipping our own creations — it was about ensuring humanity's reach extended beyond its immediate concerns.

In his home that he shared with his wife, the pediatrician Gloria Rudisch, surrounded by the tools of this endeavor — computers, musical instruments, puzzles, each representing a different facet of intelligence — Minsky seemed both present in the moment and focused on a distant horizon. While corporate America was beginning to embrace expert systems that could diagnose diseases or configure computers, he was asking more fundamental questions: not just whether machines could think, but what our resistance to that idea revealed about ourselves.

By year's end, as E.T. phoned home in theaters across America3 and Michael Jackson's "Thriller" invited us to embrace the uncanny, Minsky's provocations lingered: Were we ready to understand ourselves well enough to create minds different from our own? Did we have a choice?

"Most of us respond only to our interior goals," he observed, "but we recognize and honor those few who reach outside themselves, wittingly or unwittingly making the world of the future all right."

And perhaps that was Minsky's most lasting contribution of 1982: while others were busy proving machines could perform specific tasks — play chess, solve equations, diagnose diseases — he insisted on asking the bigger question. Not whether machines could match human intelligence, but whether the very act of trying to create thinking machines might transform human consciousness itself. His position was that the enterprise of artificial intelligence wasn't just about building smarter computers — it was about expanding the boundaries of what it meant to be human.

In 1982, as artificial intelligence was finding its first commercial applications, Minsky was suggesting something more radical: that in teaching machines to think, we might finally learn to understand ourselves — not just as we are, but as what we might become.

Two From Today

First, from

by :Mollick addresses the AGI hype: “There are plenty of reasons to not believe insiders as they have clear incentives to make bold predictions: they're raising capital, boosting stock valuations, and perhaps convincing themselves of their own historical importance.” And he notes that aspects of the tech is not demonstrating to be ‘there yet.’ But, he warns “increasingly public benchmarks and demonstrations are beginning to hint at why they might believe we're approaching a fundamental shift in AI capabilities. The water, as it were, seems to be rising faster than expected.”

Mollick dives deeper into what that rising water looks like, and ends with: “What concerns me most isn't whether the labs are right about this timeline - it's that we're not adequately preparing for what even current levels of AI can do, let alone the chance that they might be correct. While AI researchers are focused on alignment, ensuring AI systems act ethically and responsibly, far fewer voices are trying to envision and articulate what a world awash in artificial intelligence might actually look like. This isn't just about the technology itself; it's about how we choose to shape and deploy it. These aren't questions that AI developers alone can or should answer. [. . .] The time to start having these conversations isn't after the water starts rising - it's now.”

Mollick is right to note that while AI labs focus on alignment and ethics, "far fewer voices are trying to envision and articulate what a world awash in artificial intelligence might actually look like."

But, we've seen this pattern before, most recently with social media platforms like TikTok. As internal reports now reveal in this critically important article from

and Jon Haidt of :TikTok is Harming Children at an Industrial Scale

Rausch and Haidt capture how TikTok's own employees recognized their platform was corroding fundamental human capacities. As one internal report put it:

“Compulsive usage correlates with a slew of negative mental health effects like loss of analytical skills, memory formation, contextual thinking, conversational depth, empathy, and increased anxiety,” in addition to “interfer[ing] with essential personal responsibilities like sufficient sleep, work/school responsibilities, and connecting with loved ones.”1

And, the above harms mentioned only scratch the surface. It leaves out the other “clusters of harm” Rausch and Haidt identify such as: 1. Addictive, compulsive, and problematic use; 2. Depression, anxiety, body dysmorphia, self-harm, and suicide; 3. Porn, violence, and drugs; 4. Sextortion, CSAM, and sexual exploitation.

Yet here we are reckoning with the fact that the technology spread faster than our ability to understand its impact.

The parallel to AI is striking. Just as TikTok's engagement algorithms reshaped how millions think and interact before we fully grasped the consequences, AI threatens to transform society while we're still struggling to ask the right questions. And as with TikTok, by the time we fully understand the impact, it may be too late.

While recent attention has focused on national security concerns around ByteDance's Chinese ownership,4 the more immediate question may be its impact on how we think and interact. And, if TikTok is in fact eroding “analytical skills, conversational depth, and contextual thinking,” where does that leave the kids who are hooked on the platform? Consider those teenagers (many who I’ve spoken to) who recognize TikTok's harmful effects but feel powerless to disconnect.5

Mollick argues that for AI, the time for these conversations is now, before the "water starts rising." But perhaps the most important insight isn't just about timing — it's about who needs to be part of the dialogue. These questions about AI's future "aren't questions that AI developers alone can or should answer." Just as understanding TikTok's impact requires listening to affected teens and families, shaping AI's development demands voices beyond Silicon Valley's echo chamber.

The lesson from TikTok is clear: we can't afford to be passive observers of technological change. Whether it's social media algorithms or artificial intelligence, the time to question and shape these technologies is before they reshape us.

We often assume these big questions about technology's impact should be left to experts and influencers. But what if the most important conversations start smaller — at dinner tables, between friends, in quiet moments with family? A parent asking their child about TikTok habits, or a friend expressing concern about attention spans, can spark the kind of reflection that no policy paper or viral thread ever could.

Sometimes the most profound questions don't need credentials — they just need to be asked.

***

For more on this topic, and kids + phones in general, I highly recommend

’s Substack . Specifically, the article below is a great resource.Minsky’s Future Vision - The New Yorker, December 1981

Why People Think Computers Can’t Think - AI Magazine, Winter 1982

Highlights of the Supreme Court Argument on TikTok - The NY Times (gift)

Estimates of daily TikTok use in teens: 21,836,451 U.S. teens » 58% of U.S. teens using TikTok daily = 12,665,142 daily U.S. teen TikTok users (Note: these figures are only teen users. As shown in their article, TikTok has significant market penetration among under-13 year old users in the U.S.)

"And perhaps that was Minsky's most lasting contribution of 1982: while others were busy proving machines could perform specific tasks — play chess, solve equations, diagnose diseases — he insisted on asking the bigger question. Not whether machines could match human intelligence, but whether the very act of trying to create thinking machines might transform human consciousness itself. His position was that the enterprise of artificial intelligence wasn't just about building smarter computers — it was about expanding the boundaries of what it meant to be human."

Makes me wonder today with AI-automated BDR teams, if we are missing the point today as well