The year was 1981, and Japan was about to prove that sometimes the most powerful piece of technology is a story.

In a Tokyo conference room that October, as autumn leaves drifted past windows in the Akasaka district, officials from Japan's Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) unveiled their vision of the future. The Fifth Generation Computer Project would be a decade-long quest to create thinking machines - not just faster computers, but systems that could reason, learn, and converse in human language.1 The price tag: ¥100 billion ($500 million).

The technical details were ambitious but vague. What mattered was the story: while American AI researchers had spent the past decade retreating from their grandest dreams, Japan was charging forward with the full backing of its government-industrial complex. As news of the project spread through Western research labs and corporate boardrooms, it triggered what one observer would later call "a severe case of collective anxiety."

This anxiety was exactly what a struggling field needed.

At Stanford, Edward Feigenbaum was marking artificial intelligence's silver anniversary with a bittersweet reflection on its journey from academic curiosity to contested science. "Your name stuck," he wrote in the AAAI journal, addressing AI directly, "a source of pride and strength."2 But it was Japan's dramatic narrative that would give that name new power, transforming AI from a field in retreat to one that command national attention once again.

In a curious parallel that same autumn, another kind of screen was flickering to life in American living rooms. "Ladies and gentlemen, rock and roll," declared MTV's first broadcast, as footage of the Apollo 11 launch gave way to "Video Killed the Radio Star." Like Japan's Fifth Generation Project, MTV wasn't actually offering anything technically revolutionary - music videos had existed for years. What it offered was a new story about how technology could transform culture, wrapped in a package slick enough to make the future feel both inevitable and desirable.

Even as computer scientists digested Japan's challenge, IBM was preparing its own narrative pivot. For years, the company had insisted that personal computers were toys, beneath the dignity of serious computing. But on August 12, IBM unveiled its own PC, lending corporate credibility to the personal computing revolution. The machine itself was less sophisticated than many of its competitors, built from off-the-shelf parts. But IBM understood what Japan's MITI did: sometimes the messenger matters more than the message.

Inside AI labs, a similar shift was underway. The grand dreams of building human-like general intelligence were giving way to more focused ambitions. Expert Systems, which captured specific human knowledge in narrow domains, might have seemed like a retreat from AI's boldest visions. But they offered something more valuable than theoretical purity: they worked. Programs like XCON were saving companies millions by automating complex tasks like computer configuration, suggesting that limited but practical AI could be more valuable than hypothetical general intelligence.

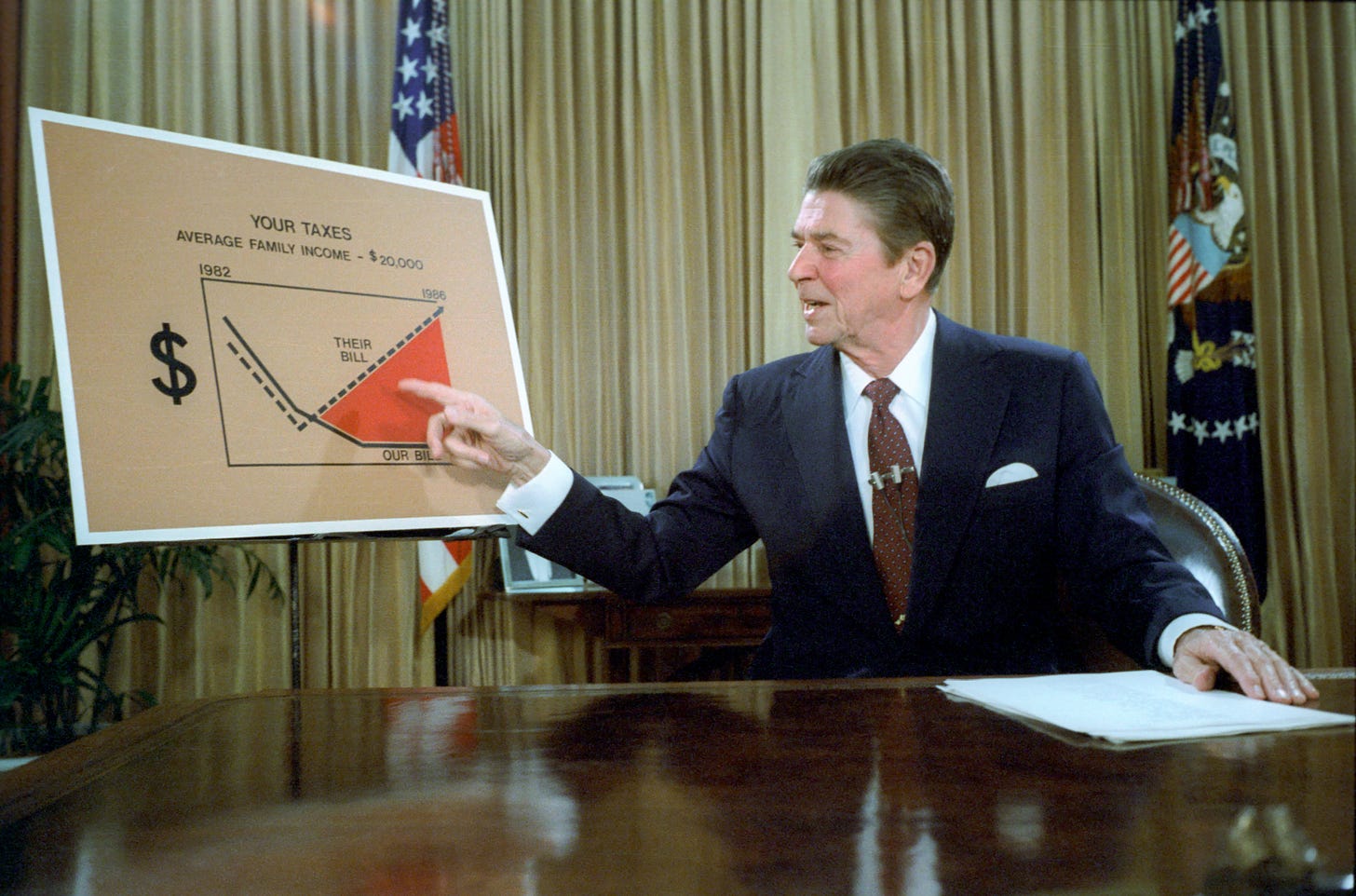

These pivots - from theory to practice, from purity to pragmatism - found their political expression in Ronald Reagan's first year as president. His economic narrative, soon dubbed "Reaganomics," repackaged complex monetary theories into simple stories about tax cuts and deregulation. Whether it would work was almost beside the point; the story itself was changing how Americans thought about their economic future.

The embrace of limited but practical goals over grandiose theories was spreading through AI labs like a pragmatic virus. At Stanford and MIT, researchers who had once dreamed of replicating human consciousness were now proudly building "expert systems" that could diagnose bacterial infections or configure computers. The field hadn't lowered its ambitions so much as focused them, like a lens concentrating sunlight into a more powerful beam.

At Berkeley, philosopher John Searle was staging his own kind of resistance to AI's pragmatic turn. His Chinese Room argument, published the year before, had posed a deceptively simple question: if a computer could perfectly simulate understanding Chinese, would it actually understand Chinese? Searle's thought experiment — involving a person who doesn't know Chinese following detailed instructions to respond to Chinese messages — suggested that even perfect simulation wasn't true understanding.

But while Searle's argument rippled through philosophy departments, AI researchers were increasingly asking a different question: did it matter? Expert systems were saving lives in hospitals, optimizing manufacturing plants, and solving real-world problems. The Japanese Fifth Generation Project wasn't promising true understanding — it was promising practical results.

John McCarthy, who had coined the term "artificial intelligence" back in 1956, watched this transformation with mixed feelings. His creation was finding commercial success by pursuing exactly the kind of narrow, practical applications he had once dismissed as mere programming. While philosophers debated whether machines could truly think, engineers were quietly building machines that could work.

The Japanese understood this shift perfectly. Their Fifth Generation Project, for all its ambitious rhetoric, was fundamentally practical. They weren't pursuing AI for philosophical reasons but for economic ones. They wanted machines that could process the complex Japanese language, automate offices and factories, and maintain Japan's competitive edge as manufacturing went digital. The story they told was bold, but the goals were concrete.

This new pragmatism was reshaping the entire technological landscape. MTV wasn't trying to revolutionize art; it was trying to sell records. The IBM PC wasn't trying to democratize computing; it was trying to keep IBM relevant in a changing market. Even Reagan's optimistic rhetoric about "morning in America" was grounded in specific promises about taxes and regulations.

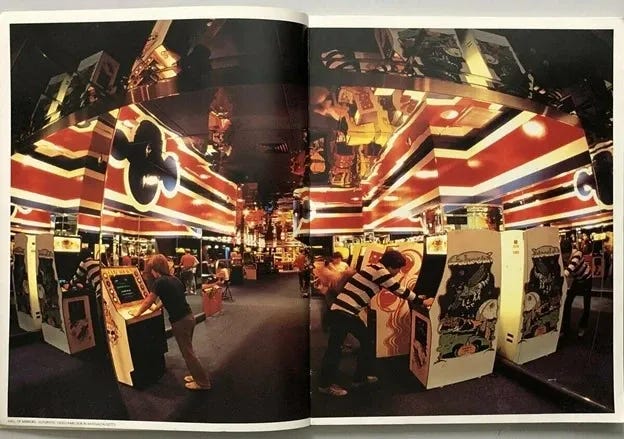

The old guard of AI might have seen this as a betrayal of their purer aspirations. But a younger generation, raised on personal computers and video games, saw it differently. When Nintendo released Donkey Kong that year, its creator Shigeru Miyamoto wasn't trying to simulate human intelligence — he was trying to create compelling gameplay. The result was more engaging than many "serious" AI projects.

In Polish shipyards, Solidarity workers were learning their own lesson about the gap between theory and practice. As martial law descended in December, their dreams of worker solidarity met the practical reality of Soviet tanks. The second oil crisis was teaching similar lessons about the limits of theoretical economics in the face of practical politics.

But something unexpected was happening as these grand dreams met practical reality. The compromises weren't killing the dreams - they were giving them new life. Expert systems might not have achieved true artificial intelligence, but they were solving real problems. Personal computers might not have revolutionized society overnight, but they were changing how people worked and played. MTV might not have transformed art, but it was creating a new visual language for a generation.

By year's end, artificial intelligence had found its second wind not by achieving its grandest ambitions, but by learning to live with - and even embrace - its limitations. As Edward Feigenbaum wrote in his silver anniversary message to the field: "What, precisely, is the nature of mind and thought? You stand with molecular biology, particle physics, and cosmology as owners of the best questions of science." The field had grown up, just as Feigenbaum had noted in his anniversary message, and like all coming-of-age stories, it involved learning to balance dreams with reality.

The future, it turned out, arrived not through philosophical breakthroughs or technological revolutions, but through stories that helped us imagine what was possible, and practical steps that helped us get there. In 1981, AI taught us that sometimes the best way to achieve your dreams isn't to chase them directly, but to tell better stories about how to get there.

Two From Today (and one from ‘81)

From

’s :And from

’ :And, a cool link back to a 1981 article by American journalist, writer, cyclist, archivist, and explorer, Steven K. Roberts, reposted on his website, Nomadic Research Labs: Artificial Intelligence: BYTE

This was my first substantial essay on AI, and fell out of an intensely stimulating two-week adventure at Stanford University that included the first International Conference on Artificial Intelligence, a LISP conference, schmoozing with some truly amazing authors, hanging out at Xerox PARC for an evening, and generally getting my brain expanded during every waking moment. It probably helped that this was in very sharp contrast to my midwest existence; even though I was doing lots of fun stuff with microprocessors, it was a rather lonely pursuit. Hobnobbing in Silicon Valley academia, even as a dilettante, was eye-opening and in some ways even life-changing.