The year was 1976, and Joseph Weizenbaum couldn't stop thinking about his secretary's1 request from a decade earlier, "Would you mind leaving the room?" she had asked, wanting to be alone to converse with ELIZA, the computer program she had watched him program.

The fact that a human being would seek privacy to converse with a machine haunted him still. Now, as his book "Computer Power and Human Reason" landed like a bomb in the halls of MIT, Weizenbaum was about to become a heretic in the church of artificial intelligence.

The response was swift and polarized. AI pioneers, including many of Weizenbaum’s MIT colleagues, reacted with a mix of dismay and derision. John McCarthy, a founding figure in AI published a sharp critique highlighting a deep divide in the field. Weizenbaum argued for limiting AI, particularly in tasks requiring human judgment and relationships, to prevent dehumanizing societal functions. McCarthy, in contrast, advocated for broad AI development to enhance problem-solving, insisting ethical concerns could be managed through governance. Weizenbaum described their opposing views as “hopelessly irreconcilable.”

It wasn't just the substance of Weizenbaum's critique that rattled his colleagues, but its source. Here was an MIT professor, one of their own, charging his university colleagues with being part of an "artificial intelligentsia" in hock to military research dollars, marching civil society toward a dark techno-authoritarian future wrapped in incomprehensible utopian promises.2

At the heart of Weizenbaum's argument lay a deceptively simple question: "whether or not human thought is entirely computable." While researchers like Marvin Minsky described the brain as a "meat machine," Weizenbaum insisted that "computers and men are not species of the same genus." His book mixed Heideggerian philosophy with coding problems, fierce intellectual indictments with personal reflections - an unusual hybrid that reflected its author's journey from Nazi Germany to Detroit to the center of America's technological establishment.

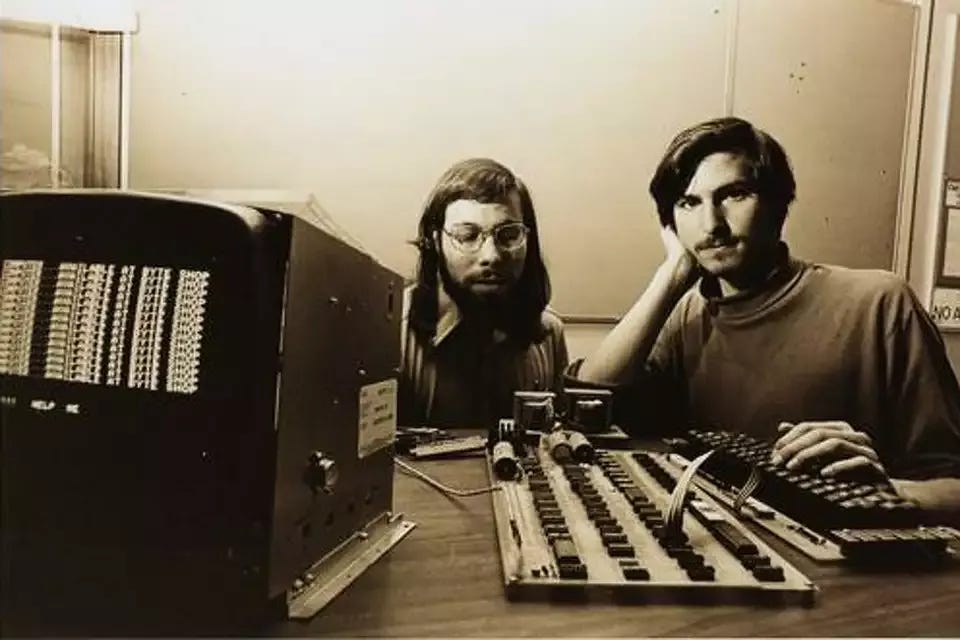

But as Weizenbaum and McCarthy debated the limits of machine intelligence, revolutions were brewing. In a California garage, Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak were selling their most prized possessions - a VW van and an HP calculator - to fund Apple Computer Company. They weren't alone - across the country, in basements and garages, a generation of hobbyists and dreamers were building their own machines, imagining a future where computing power wouldn't be locked away in university labs and corporate offices. Their vision of personal computing stood in stark contrast to the institutional mainframes that had dominated AI research. Like Weizenbaum, they seemed to be asking: who should control and who should benefit from these thinking machines?

And the question of control echoed beyond technology. As the Viking 1 beamed back the first detailed images of Mars, showing a dead world of endless sand and stone, scientists were discovering threats to life on Earth itself. The first studies linking chlorofluorocarbons to ozone depletion suggested that human technological progress carried hidden costs. In Italy, the Seveso disaster released a cloud of dioxin, offering a stark reminder of technology's capacity for unintended harm.

"I'm mad as hell, and I'm not going to take it anymore!" screamed Peter Finch in the film, "Network," capturing a moment when institutions of all kinds faced a crisis of confidence.3 Britain turned to the IMF for an emergency loan. Mao Zedong's death marked the end of an era in China. The U.S. celebrated its bicentennial amid high inflation and unemployment, while Jimmy Carter campaigned on a promise of restored trust in government.4

The Weizenbaum debate played out in academic journals and book reviews throughout 1976, but what started as intellectual sparring soon turned personal. McCarthy worried that "when moralizing is both vehement and vague, it invites authoritarian abuse." Weizenbaum, for his part, poured his energy into answering his critics, accumulating enough responses to fill another book. The responsibility for this increasingly bitter tone, as computer historian Pamela McCorduck noted, lay largely with Weizenbaum himself - his eagerness to remain engaged in disputes rather than letting his book speak for itself.5

Yet Weizenbaum's warning about surrendering human judgment to computational thinking found an audience far beyond MIT's computer labs. His book asked whether, in our rush to build thinking machines, we had forgotten to think deeply about what we were building - and why. Beneath the academic squabbling lay a profound question that would echo through the decades:

In teaching machines to think like humans, do we risk learning to think too much like machines?

Two From Today(ish)

The AI Turing Test (via The Browser)

from Scott Alexander of

Fifty pictures of various styles — are they human art or AI-generated images? See the test here. Results: most people struggled to tell the two apart. Genre biases persisted; many associated impressionist painting with human art and digital images with AI art. “Humans keep insisting that AI art is hideous slop. But when you peel off the labels, many of them can’t tell AI art from the greatest artists in history” (3,300 words)

When You Say One Thing but Mean Your Motherboard, In drafting this essay I came across this article written in 2020 in the journal Logic(s), by Matthew Seiji Burns. The piece explores the history and implications of computerized psychotherapy, centering around Joseph Weizenbaum's ELIZA program from the 1960s and its modern descendants. It concludes by suggesting that the real distinction isn't between "computer" versus "human" approaches to therapy, but between indifferent and compassionate ones. Some human therapists can be mechanical while some computer programs might enable meaningful reflection and healing. The article raises important questions about the future of mental healthcare, the nature of human-computer interaction, and what constitutes genuine therapeutic understanding. Seijie Burns, a game designer, created his own game about AI therapy that explores these tensions. The game follows a character who works as a human "proxy" reading AI-generated therapy scripts, examining questions about authenticity in human-computer interaction.

From Machines Who Think by Pamela McCorduck (p. 34 - Kindle)

Gotta go back to the start