The year was 1956 and in a quiet corner of New Hampshire, ten men gathered to consider the same question that Alan Turing had posed six years prior: ‘Can machines think?’

“They had in common a belief (more like a faith at that point) that what we call thinking could indeed take place outside the human cranium, that it could be understood in a formal and scientific way, and that the best nonhuman instrument for doing it was the digital computer.”1

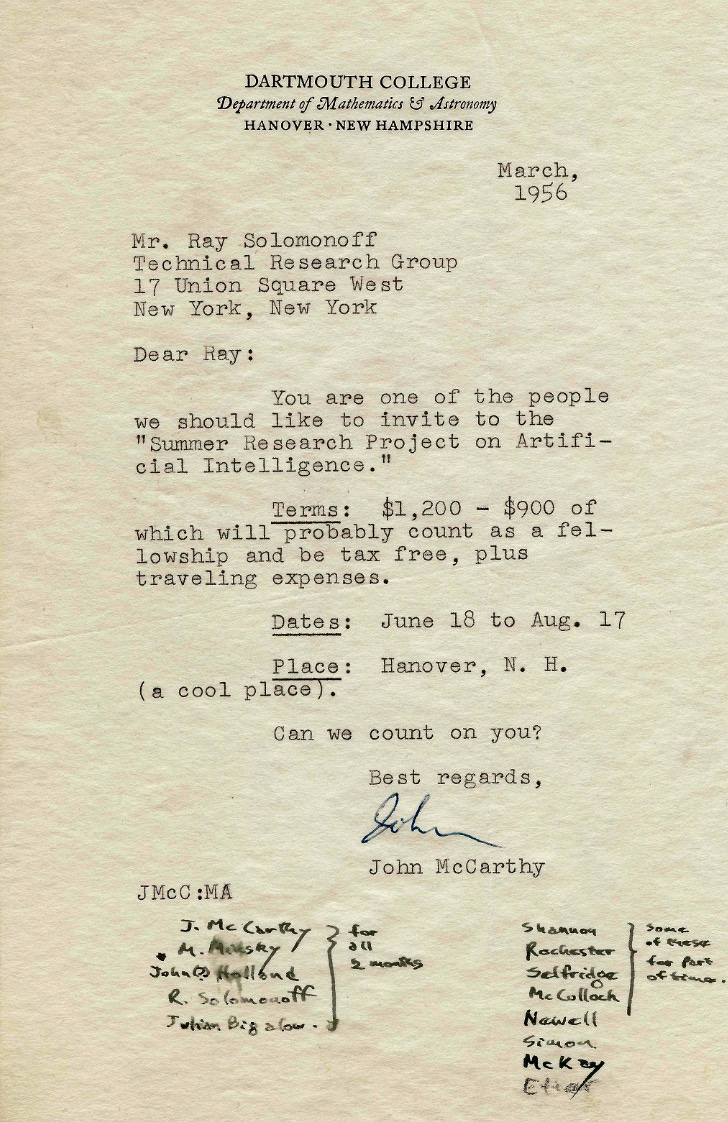

John McCarthy, a young mathematician born in Boston to parents who believed that intellectual curiosity was the greatest inheritance they could bestow, had brought them together. While in Princeton's mathematics department, McCarthy had met Marvin Minsky, another student intrigued by the notion of intelligent machines. After graduation, McCarthy's path wound through Bell Labs and IBM, where he worked alongside Claude Shannon, the architect of information theory, and Nathaniel Rochester, a pioneer in electrical engineering. These encounters, like neurons firing in the brain of progress, sparked connections that would lead to a summer gathering of minds, all pondering the possibility of thinking machines.2

Now at Dartmouth, McCarthy had persuaded Minsky, Shannon, and Rochester to help him organize what they called the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence. The term "artificial intelligence" was McCarthy's invention, he wanted to distinguish it from other related fields, though he later admitted that no one really liked the name: "after all, the goal was genuine, not 'artificial,' intelligence—but I had to call it something."3

For eight weeks, from June to August, they occupied the top floor of the Dartmouth Math Department. The summer air was thick with ideas and the smell of chalk dust. They talked and argued and drank tea, their conversations punctuated by the rustle of papers and the occasional thud of a heavy dictionary being opened to look up words like "heuristic," which some hoped might hold the key to machine intelligence.

Some, like Ray Solomonoff, Marvin Minsky, and John McCarthy, stayed for the entire duration, their minds buzzing with possibilities. Others came and went, like thoughts in a vast, collective brain. On some days, three men would gather around a blackboard; on others, eight would crowd into a room, their excited voices overlapping like waves in a chaotic sea of ideas.

They discussed grand visions and minute details. How to make a machine play checkers, or prove geometry theorems, or understand human language. Ross Ashby brought a strange device called a "homeostat," a metal box filled with water and magnets that was supposed to model the adaptability of the brain. They stared at it, wondering if the secret to intelligence might be hiding in its mysterious workings.

As the weeks passed, subtle divisions began to form. Some, like Newell and Simon, advocated for symbolic logic and heuristics, believing that intelligence could be built from rules and representations. Others, like Solomonoff, were drawn to probability and induction, imagining machines that could learn from experience and make educated guesses about the future.

Marvin Minsky, who had once believed that intelligence emerged from networks of artificial neurons, found himself swayed by ideas about symbols and prediction. It was as if he had set out to build a bird and instead discovered the principles of flight.

John McCarthy tried to rally the group around the game of chess, seeing in its complex rules and strategies a microcosm of human thought. But each man had his own vision, his own pet theory about what intelligence truly meant and how it might be recreated in silicon and steel.

By summer's end, they had not built a thinking machine. They had not even agreed on what such a machine would look like or how it might function. But they had done something perhaps more important: they had opened a door to a future that was both thrilling and terrifying in its implications, they had launched a new field called artificial intelligence, setting in motion a revolution that would eventually touch every aspect of human life in the decades to come.4

And meanwhile, faraway, the western-world’s map of Africa looked like a poorly designed jigsaw puzzle, with most of the pieces still stuck together. There were only four independent countries on the entire continent - Liberia, Ethiopia, Egypt, and Libya - but that was about to change. Morocco and Tunisia looked at the lines that France had drawn around them and decided those lines didn't make much sense anymore. France pretended it didn't care, like a child who says they didn't want to play anyway after not being picked for a team. And suddenly the idea of independence started to look very attractive to a lot of other places that had been colored pink or blue or yellow on European maps for a very long time.5

Back in America, people were witnessing changes that made some wonder if anything was sacred anymore. A young man from Mississippi appeared on their television screens, gyrating his hips in a way that made half the country feel things they'd never felt before and the other half feel things they wished they'd never felt. The King had arrived, piped into the country's living rooms no less, shaking up more than just his legs.

And, as if to provide an escape route from this cultural upheaval, the government decided that what the country really needed was more roads. The Federal-Aid Highway Act6 promised to stitch the nation together with ribbons of asphalt, changing the landscape of America forever. As these highways stretched out, they pulled people away from city centers, and some people thought it was silly to try and find a solution to real problems by making it easier to drive away from them, and others said it was giving birth to a new American dream. White picket fences sprang up where corn fields once stood, shopping malls blossomed like concrete flowers along the interstates, and many said, this was progress, and others knew that progress rarely marches in a straight line, even when guided by freshly painted highway lanes.7

While picket fences were going up across the land, they figured out how to lay a telephone cable across the Atlantic Ocean, which meant that people could misunderstand each other across thousands of miles of water instead of just across a dinner table.8 IBM made a machine that could remember things even when it wasn't plugged in, which seemed very clever at the time, though no one was quite sure what sort of things a machine might want to remember.9 And another company invented a way to record television shows, which meant that people could watch the same things over and over again, in case they hadn't understood them the first time.10

But even as the world got smaller in small places, the cracks got bigger in others. In Egypt, a man said that a canal that ran through his country should belong to his country, which seemed logical to some people and terribly upsetting to others. The upset people sent soldiers and ships, and suddenly a lot of the world was arguing about who owned a ditch filled with water.11 And in Hungary, people decided they'd like to make some decisions for themselves, but the Soviet Union said that making decisions was the sort of thing best left to experts in Moscow. The Hungarians disagreed, and the Soviets sent tanks to explain their point of view more clearly.12

And through all of this, as some lines on the map were erased and others were drawn more deeply, and a group of men gathered in a small town in New Hampshire wondering if it might be possible to make a machine that could think, it still wasn’t quite clear if humans had figured out how to do it themselves.

Machines Who Think: A Personal Inquiry into the History and Prospects of Artificial Intelligence, Pamela McCorduck

Machines of Loving Grace, John Markoff

Artificial Intelligence: A Guide for Thinking Humans, Melanie Mitchell