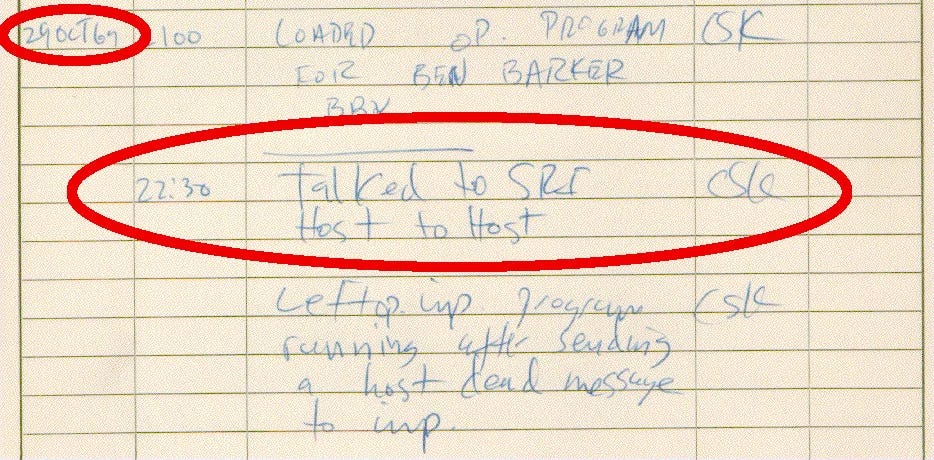

The year was 1969, and in a cavernous computer lab at UCLA, the future was about to be born with all the fanfare of a hiccup.

Charley Kline, a young programmer with a penchant for nocturnal coding sessions, sat before the SDS Sigma 7 - a hulking beast of a computer that occupied roughly the same square footage as a modest apartment. The clock ticked towards 10:30 PM on October 29th, the lab silent save for the low hum of machinery and the occasional click of keys under Kline's fingers.

Across the room, an appliance-sized device known as the IMP (Interface Message Processor) stood ready for its debut. Built by Bolt, Beranek and Newman after tech giants IBM and AT&T had scoffed at the project, the IMP was about to become the midwife to the digital age.

Miles away in Menlo Park, California, Bill Duvall sat before a similar setup at the Stanford Research Institute, waiting on the other end of a telephone line. The two men, separated by hundreds of miles but united by copper wire and silicon, were about to attempt something never before achieved - a long-distance conversation between computers.

As Kline's fingers hovered over the keyboard, one can imagine the ghost of Samuel Morse whispering in his ear, urging him to prepare some profound message for posterity. But this was no carefully choreographed moon landing or public unveiling. This was science in its raw, unvarnished form - two guys trying to get a machine to talk to another machine.

Kline began to type: L-O-G-I-N.

"Got the L," Duvall's voice crackled over the phone line.

"O," Kline typed next.

"Got the O," Duvall confirmed.

And then, as Kline's finger descended towards the 'G', the future arrived not with a bang, but with a crash. The SRI system stumbled, hiccupped, and unceremoniously keeled over.

In that moment, as Kline and Duvall worked to revive their recalcitrant machines, neither man could have known that they had just midwifed the birth of the Internet. The message was incomplete, the system imperfect, but in those two letters - 'LO' - lay the seed of a revolution.1

An hour later, after much tinkering and muttered imprecations, success! The full 'LOGIN' made its way from UCLA to SRI. Kline scribbled a note in the logbook, Duvall grabbed a burger and a beer on his way home, and the world continued to spin, blissfully unaware that everything had just changed.

In the grand tapestry of human achievement, this moment might seem a loose thread, barely worth noting. And yet, from this humble beginning - this 'LO' heard 'round the world - would spring a network that would one day connect billions, reshape societies, and redefine what it means to be human in the digital age.

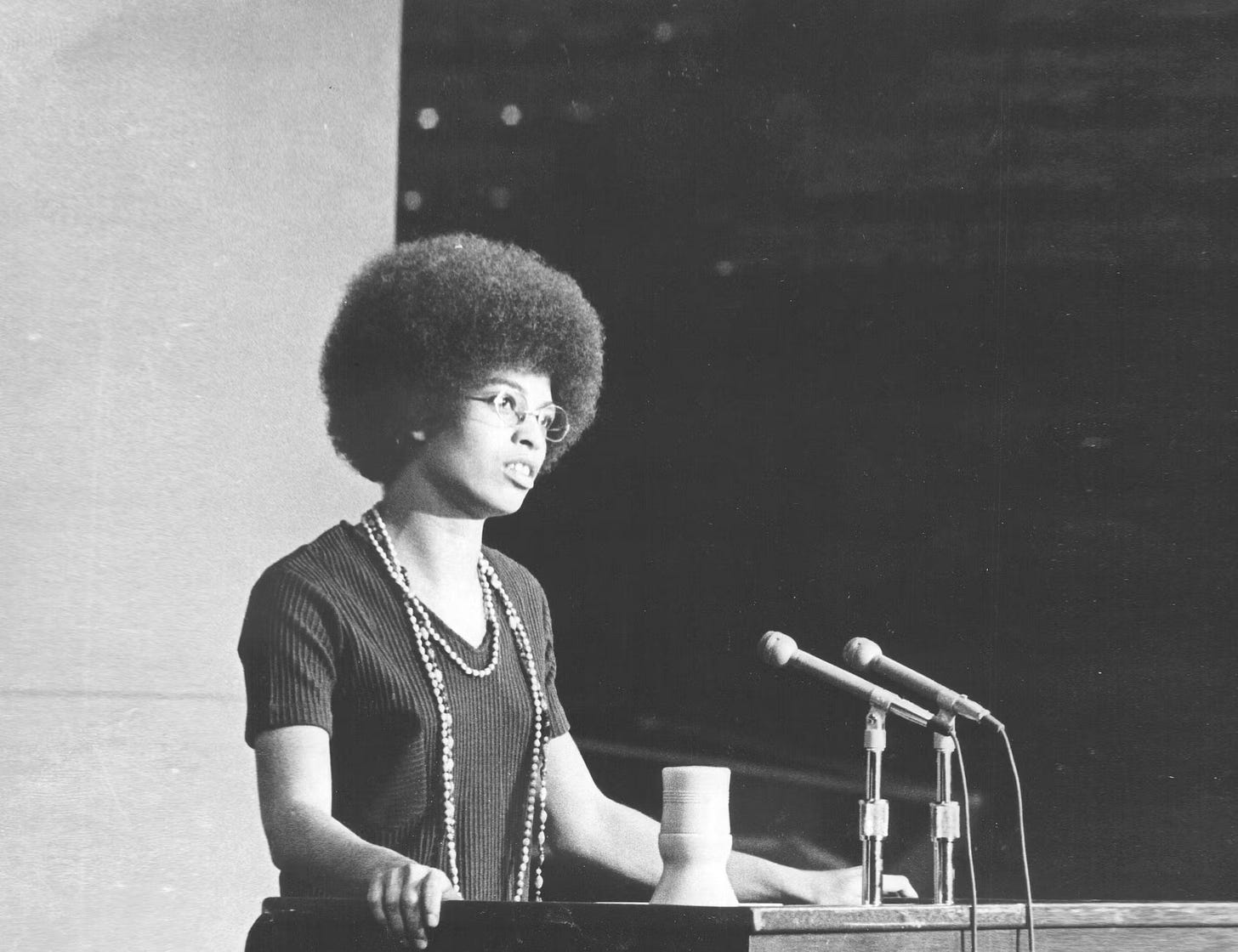

As Charley Kline's fingers tapped out the future in that UCLA computer lab, the campus was still buzzing from a different kind of revolution. Just weeks earlier, on October 6th, the halls of Royce Hall had swelled with over 2,000 students, all clamoring to hear the words of a young philosophy professor named Angela Davis.2

Davis, a 25-year-old scholar, originally from Birmingham, Alabama, where she had personally known several of the girls killed in the 1963 16th Street Baptist Church bombing, had become the epicenter of a storm that raged far beyond the ivy-covered walls of academia. Hired as part of Chancellor Charles E. Young's initiative to diversify the faculty, Davis found herself at the heart of a battle over academic freedom, civil rights, and the very soul of American education.

The trouble had begun even before she could teach her first class. On op-ed in the student newspaper claimed the philosophy department hired a member of the Communist Party — which Davis publicly confirmed, creating an uproar with the university regents. They, along with then-Governor Ronald Reagan, wanted Davis out. Suddenly Davis found her salary withheld and her position in jeopardy. The irony was thick enough to cut with a knife - here was UCLA, birthing the future of global communication through ARPANET, while simultaneously grappling with the limits of free speech and association in its own backyard.

As the regents moved to fire Davis, citing her Communist Party membership, she stood her ground. Davis told the standing-room-only crowd that education’s goal should be “to create human beings who possess a genuine concern for their fellow human beings.” She added that, “Education should not mold the mind according to a prefabricated architectural plan. It should rather liberate the mind."

In those words, one could almost hear the echo of the ARPANET's first transmission - 'LO' - as if the network itself was trying to login to a future of unrestricted information exchange. Both Davis and the fledgling Internet represented a challenge to the status quo, a promise of connection and communication that transcended traditional boundaries.

The UCLA community rallied around Davis. Students threatened to withhold grades, professors dug into their own pockets to cover her missed salary, and Chancellor Young himself argued for her reinstatement. It was as if the entire campus was engaged in its own form of packet switching, routing support and solidarity around firewalls of bureaucracy and prejudice.3

As autumn deepened and the leaves turned, UCLA found itself at the crossroads of two revolutions. In one corner of the campus, young programmers were birthing the digital age with lines of code and clunky hardware. In another, a young black woman was fighting for her right to teach, to think, to exist in spaces long denied to people who looked like her.

Both struggles were, at their core, about communication - about who gets to speak, how they get to speak, and who gets to hear them. As ARPANET took its first tentative steps towards a globally connected world, Angela Davis was alluding to the idea that true connection may require more than just wires and protocols. It may require courage, compassion, and a willingness to hear voices that challenge our preconceptions.

As Angela Davis fought for her right to teach and ARPANET sent its first tentative messages, another revolution was brewing in the realm of artificial intelligence. In a quiet corner of MIT, two brilliant minds were about to change the course of AI research for years to come.

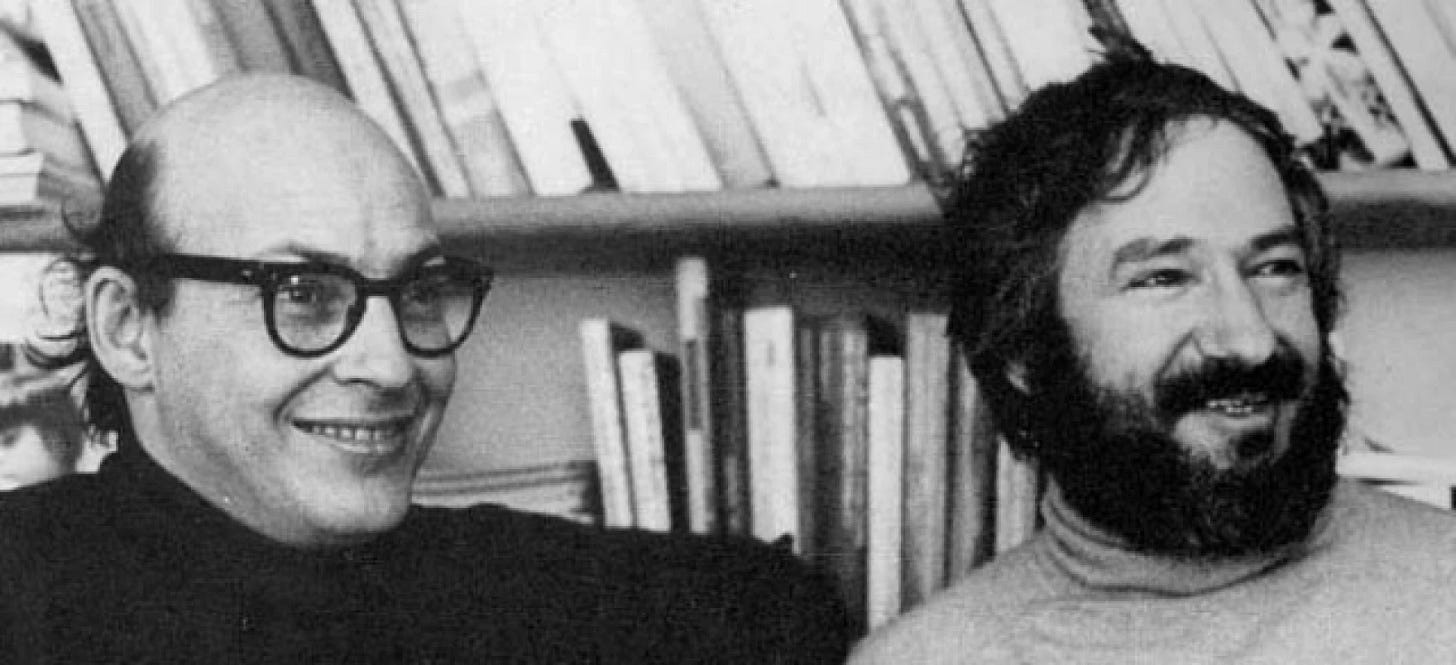

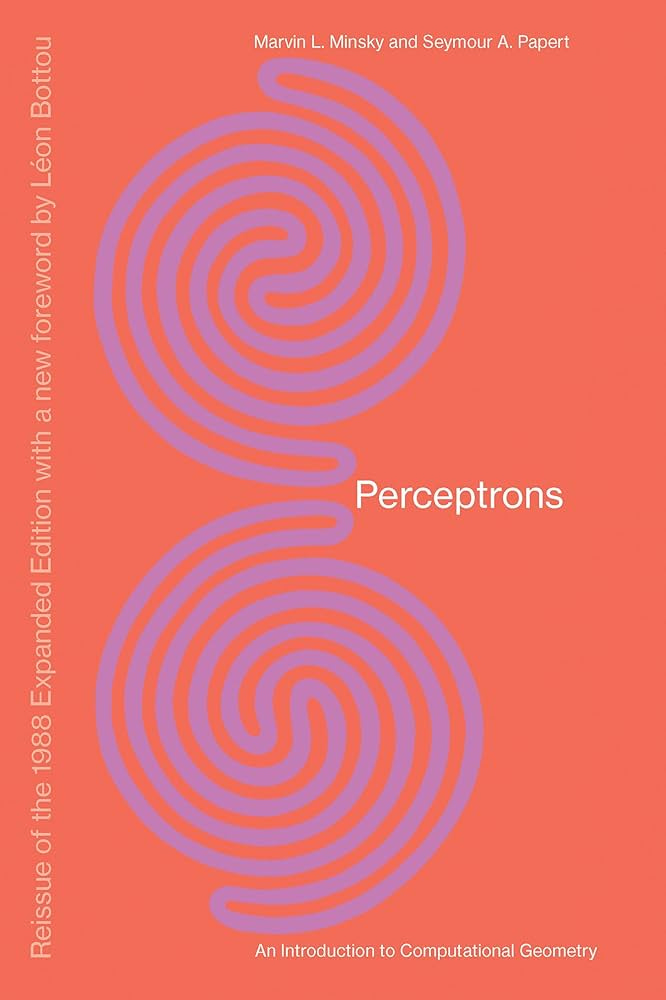

Marvin Minsky and Seymour Papert, collaborators since 1963, had spent years meticulously dissecting the limitations of the Perceptron, a pattern recognition machine designed by Frank Rosenblatt in 1959. The Perceptron had once been hailed as the future of AI, capable of learning to recognize shapes and patterns much like a human brain. But Minsky and Papert saw flaws in this rosy vision.

In 1969, they published "Perceptrons," a book that would become both a mathematical tour de force and a controversial turning point in AI research. With elegant proofs and rigorous analysis, Minsky and Papert demonstrated the fundamental limitations of single-layer Perceptrons. They showed that these machines, for all their promise, couldn't perform some basic tasks like determining whether a line drawing was fully connected or recognizing patterns that weren't locally visible.

The impact was seismic. As Minsky later reflected, "There had been several thousand papers published on Perceptrons up to 1969, but our book put a stop to those." The field of neural networks, which had been buzzing with excitement and possibility, suddenly fell silent.

It was a moment of both triumph and unintended consequence. The book's mathematical brilliance was undeniable, earning rave reviews and establishing computer science as a field with its own fundamental theories. But it was, in Minsky's words, "too good." By solving all the easy problems, they left little for students and young researchers to work on. The result was a decade-long winter in neural network research.

As Minsky and Papert were reshaping the landscape of AI, another breakthrough was quietly starting to take place in the background. Arthur Bryson and Yu-Chi Ho described an optimization technique for multi-stage dynamic systems that laid the foundation for what would later be recognized as backpropagation, an algorithm that would eventually breathe new life into neural networks. But in the shadow of "Perceptrons," this work would remain largely overlooked for years.

The irony wasn't lost on Minsky. Years later, he would realize that for all its limitations, the Perceptron was "actually very good" for certain tasks. He mused that nature might well make use of such simple, efficient learning devices in the brain.

While Minsky and Papert were redefining the boundaries of machine intelligence, Neil Armstrong was taking his "one small step" onto the lunar surface, a giant leap for human ambition and technology. The Apollo 11 mission, powered by computers less powerful than a modern smartphone, demonstrated both the promise and the limitations of our technological reach.4

Meanwhile, in a muddy field in the Catskill Mountains of upstate New York, the Woodstock festival was giving voice to a generation's hopes and fears. As Jimi Hendrix's electrifying rendition of the Star-Spangled Banner echoed across the farmland, it seemed to embody the contradictions of the age - tradition and revolution, harmony and discord, all intertwined.

In Washington, President Nixon was unveiling his "new economics,"5 a set of policies aimed at curbing inflation and unemployment. But even as he spoke of economic stability, the nation was being torn apart by the escalating conflict in Vietnam. Anti-war protests swept across college campuses, with chants of "Give peace a chance."

And in the midst of that year, champion of women's rights, Betty Friedan was articulating a vision of reproductive freedom. Speaking at the First National Conference on Abortion Laws, she declared, "If we are finally allowed to become full people, not only will children be born and brought up with more love and responsibility than today, but we will break out of the confines of that sterile little suburban family to relate to each other in terms of all of the possible dimensions of our personalities—male and female, as comrades, as colleagues, as friends, as lovers. And without so much hate and jealousy and buried resentment and hypocrisies, there will be a whole new sense of love that will make what we call love on Valentine’s Day look very pallid.”6

As the year drew to a close, the Cuyahoga River in Ohio caught fire,7 a vivid illustration of the environmental cost of unchecked industrialization. It was a stark reminder that even as we reached for the stars and dreamed of thinking machines, we were still grappling with the most fundamental challenges of our existence on this planet.

And in Northern Ireland, the Troubles escalated, a painful reminder that even as technology advanced, ancient grievances could still tear societies apart. Meanwhile, on the other side of the Atlantic, Adam Fortunate Eagle (born Adam Nordwall), a Chippewa Indian, sailed past Alcatraz Island, proposing to purchase it for $24 in beads and cloth—a poignant echo of Manhattan's legendary sale. Two weeks later, Native American activists would occupy the island for over 18 months, their protest a stark reminder that America's own ancient wounds remained unhealed.8 From Belfast to San Francisco Bay, 1969 saw the ghosts of history rising to challenge the narratives of progress and unity.

In the grand tapestry of human achievement, these moments might seem like loose threads, footnotes, barely worth noting. And yet, from this humble beginning - this 'LO' heard 'round the world, this crash of a Perceptron, this step on the moon - would spring a network that would one day connect billions, reshape societies, and redefine what it means to be human in the digital age.

Two From Today

AI news this week was dominated by the Nobel Prizes in Physics and Chemistry being awarded to breakthroughs in AI. Below are three perspectives.

This Nobel Prize Matters by Azeem Azhar (may be paywalled)

Two Nobel Prizes for AI, and Two Paths Forward by Gary Marcus

A Shift in the World of Science by Alan Burdick and Katrina Miller