The year was 1963, and the world teetered between logic and chaos, reason and passion, the programmed and the spontaneous.

In a cool, fluorescent-lit lab at MIT's Lincoln Laboratory1 in Lexington, Massachusetts, a young researcher named Ivan Sutherland hunched over a flickering screen. Sutherland, a disciple of Claude Shannon and friend of Marvin Minsky, held a light pen, preparing to conjure lines and shapes onto the screen out of thin air. This was Sketchpad2, the world’s first computer-aided design program, or graphical user interface (GUI).3 It conjured a future where machines could understand and create visual language as easily as humans and it showed for the first-time that computers could be used for more than just text-based processing or calculations.

In the lab, John Fitch, MIT science reporter, stood next to the hulking TX-24, one of the first digital computers in which “transistors supplanted vacuum tubes,” and spoke with Professor Steven Coons, who introduced Sutherland’s demonstration on camera, by saying:

“John, we’re going to show you a man actually talking to a computer in a way that’s far different than it’s ever been possible to do before . . . He’s going to be talking graphically. He’s going to be drawing, and the computer is going to understand his drawings.”

As Sutherland worked, he wasn't just solving a pre-defined problem. He was exploring and investigating ideas in full cooperation with the machine. This was a far cry from the conventional use of computers, where every step had to be meticulously planned and programmed in advance.

"In the old days," Professor Coons explained, "to solve a problem, it was necessary to write out in detail on a typewriter or in punch card form all of the steps, all of the ritual that it takes to solve the problem. Because a computer is very literal-minded."

But Sketchpad was different. It made the computer "almost like a human assistant," seeming to have an intelligence of its own — though, as Professor Coon was quick to point out, it was “only the intelligence they had put into it.”

Meanwhile, in Birmingham, Alabama, fire hoses and police dogs tore into crowds of protesters, their skin color an unsolvable variable in America's equation. The elegant logic of "all men are created equal" crashed against the brutal reality of segregation. Here, there were no clean lines or perfect circles.

In Washington D.C., while engineers put the finishing touches on ASCII5 - intended to teach machines a common language - humans found new ways to talk past each other. Politicians spoke of domino theories and missile gaps, their words encoding fear and mistrust as surely as any binary code.6

Across the ocean, in a divided Berlin, families pressed against a concrete wall, their tears and whispered goodbyes defying the cold calculus of geopolitics. Even as JFK declared, "Ich bin ein Berliner" in an attempt to transcend the binary logic of East and West, the wall still stood as a monument to the failure of rational actors.7

In university computer labs across the country, researchers dreamed of artificial neurons firing in perfect binary - on or off, yes or no, 0 or 1. Yet beyond those walls, Betty Friedan's "The Feminine Mystique" hit bookstores like a bomb, shattering the simplistic either/or of prescribed gender roles. Friedan's work revealed a spectrum of human desire and potential that defied easy categorization, a complexity that would challenge social norms for decades to come.8

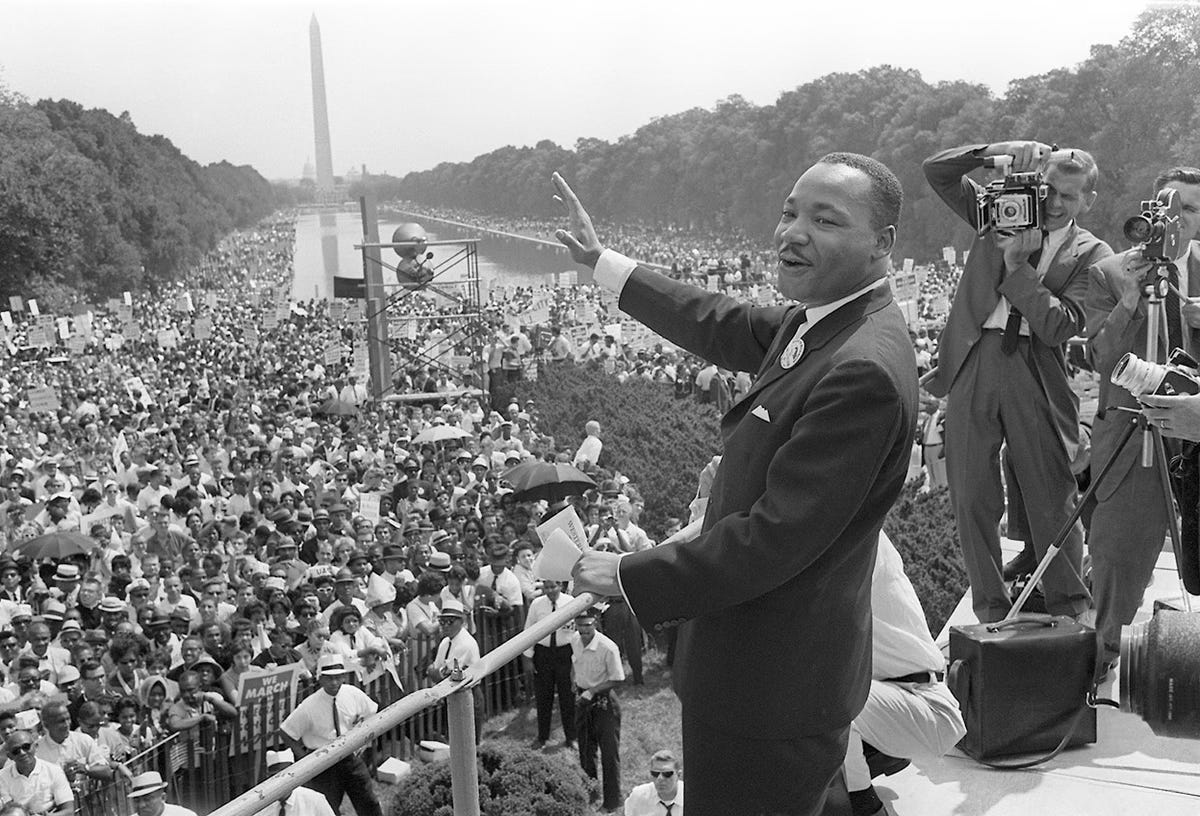

And, in the sweltering heat of Washington D.C., a sea of humanity surged towards the Lincoln Memorial. No flowchart could capture the rage of a people denied their humanity, no decision tree could map the path to justice. Bodies pressed against bodies, sweat mingled with tears, and the air thrummed with a voltage no computer could measure. When Martin Luther King Jr. stepped up to the microphone, his "I Have a Dream" speech defied any algorithm, its power lying in the realm of the unquantifiable - hope, faith, and the long arc of the moral universe.

Back in the sterile confines of Carnegie Mellon, Allen Newell and Herbert Simon fine-tuned their General Problem Solver (GPS), an evolution of their Logic Theorist work they had started together while working at the RAND corporation in 1957. Their comprehensive guide to the GPS9, prepared for the U.S. Air Force via the RAND Corporation, was preceded by their 1961 paper: “GPS - A Program that Simulates Human Thought.”10

Yet, GPS didn't know it was solving problems any more than a slide rule knows it's calculating, but its creators hoped it might crack the code of human thought, imagining a world where every problem could be broken down into neat subgoals, where reason always triumphed over emotion. It was a program designed to break down complex issues into manageable chunks, solving them through logical deduction. It was an attempt to distill the essence of human problem-solving into a set of universal rules.

But in Dallas, Texas, on November 22nd, the world confronted a problem no machine could solve after a bullet shattered the skull of a president and the illusions of a nation. As shots rang out and a president slumped forward, the nation plunged into a nightmare of uncertainty and grief. In the days that followed, as Walter Cronkite's voice cracked on national television and a young widow stood vigil over a flag-draped coffin, the inadequacy of pure logic in the face of human emotion was laid bare.11

Yet even as the world spiraled into chaos, the dreamers of artificial intelligence persisted. Far from the tear gas and turmoil, they fed their machines logic puzzles and checkers games, watched them prove simple theorems, and imagined a future where silicon minds might make sense of a world that seemed to defy all logic, and succeed where human reason had failed.

But the world of 1963 refused to be solved. It seethed and boiled, a cauldron of hope and hatred, of progress and prejudice. As 1964 lurked just around the corner, the gap between the sterile logic of machines and the messy reality of human existence yawned wide. The future arrived in bits and bytes, in protest songs and police batons, in the quiet hum of computers and the roar of a world in upheaval.

Perhaps the greatest irony was this: as researchers strove to create machines that could think like humans, the events of 1963 served as a powerful reminder of just how beautifully, terribly, and irreducibly human we truly are.