Note:

Continuing in the 1960s style of reporting, known as New Journalism, this week I leaned extra-heavily on Claude to help me mimic the style of Tom Wolfe’s Esquire article titled: “There Goes (Varoom! Varoom!) That Kandy Kolored (THPHHHHHH!) Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby (Rahghhhh!) Around the Bend (Brummmmmmmmmmmmmmm) (Yes, that was the actual printed title.)

Wolfe’s article, known as a hallmark of the New Journalism style, used a vivid and experimental writing style, that blended literary techniques with traditional journalism, to capture the flashy, exuberant world of custom car culture in Southern California. In our case, we’ve set the article as a visit to the New Jersey General Motors plant that was home to the world’s first industrial robot in October of 1962.

The Metal Man Cometh

October 23, 1962. Ewing, New Jersey.

BRRRRRNNNNGGGG! The factory whistle cuts through the crisp autumn air like a knife through warm butter, but nobody flinches. Not today. Not when the world might end tomorrow.

I pull into the parking lot of the General Motors plant, tires crunching over gravel still wet from last night's nervous rain. The radio crackles—more news about Soviet ships, missile sites, blockades. Khrushchev's bald head and Kennedy's perfect hair dance in my mind like prize fighters sizing each other up.

West Trenton stretches out around me, a patchwork quilt of modest homes and small businesses, threaded through with the silver ribbon of railroad tracks. The Delaware River, not far off, whispers promises of Philadelphia downstream, New York upstream, the artery of commerce that feeds this bustling, nervous nation. But here, squeezed between the tracks and Parkway Avenue, the GM plant looms like a steel-and-concrete colossus, a temple to American industrial might.1

Maple trees, their leaves a riot of reds and golds, line the streets—nature's own attempt at a counter-revolution against the grave-faced men hurrying into the plant. They clutch newspapers and transistor radios, hungry for news, any news, that might tell them the world isn't ending.

But here, in this modern-day Olympus where gods of industry hammer out the future, another revolution is unfolding. One that doesn't need missiles or manifestos. Just servos, hydraulics, and a dream plucked straight from the pages of Amazing Stories.

I step out of the car, straighten my tie (what does one wear to meet the future, anyway?), and head towards the main entrance. The air is thick with the smell of oil, metal, and... is that fear? No, not fear. Anticipation. The kind that makes your skin prickle and your heart race.

A foreman named Joe (they're always named Joe, aren't they?) meets me at the door. His face is a map of worry lines, but his eyes sparkle with an excitement that seems almost obscene given the headlines. "You here to see the robot?" he asks, eyebrow cocked like he's letting me in on a government secret. Which, given the circumstances, feels about right.

"Lead the way, Joe," I say, trying to sound nonchalant. As if I visit factories harboring mechanical men every Tuesday.

We push through heavy double doors, and suddenly, I'm Alice tumbling down the rabbit hole into a clanking, hissing, whirring wonderland. Conveyor belts snake through the air like metal rivers. Sparks fly from welding stations like tiny, man-made stars. And there, in the midst of it all, stands... IT.

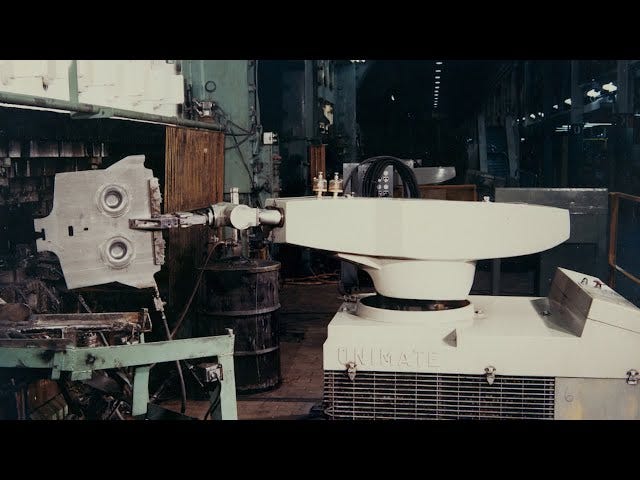

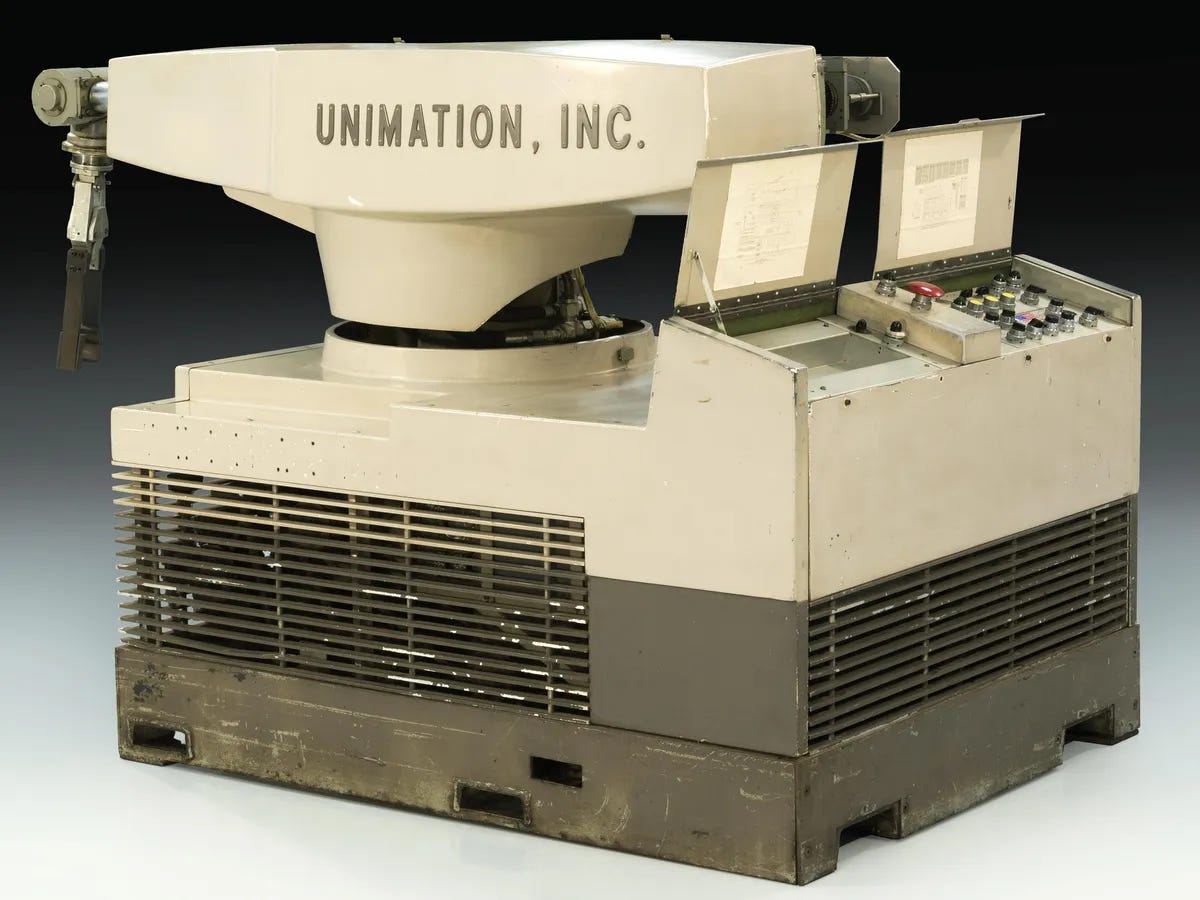

The Unimate.

Six feet of hydraulic muscle and electronic brains. A tangle of wires and tubes that would make Dr. Frankenstein weep with envy. It doesn't look human—thank God, or we'd all be out of a job faster than you can say "I, Robot." No, the Unimate looks like what it is: a machine built to work. To never tire, never complain, never ask for a raise or a coffee break or two weeks in Florida come winter.

As I watch, its arm swings with eerie grace (WHOOSH!), plucks a piece of scalding metal from a die-casting machine (CLANK!), and places it precisely where it needs to go (THUNK!). Over and over and over again. Poetry in motion, if your idea of poetry involves precision engineering and the death of the coffee break.

Joe grins at me, pride radiating off him like heat from a furnace. "Ain't she somethin'?" he says, patting the Unimate's base like it's a prized racehorse. "Been here since last year. Big wigs kept it quiet mostly, cause they didn’t know if it was gonna work out. But look at it now! Drops those red-hot door handles and other parts into pools of cooling liquid, nobody liked doing that job anyway. And best part, doesn't need lunch, doesn’t want to join any union. Just works."

I nod, mesmerized by the rhythmic dance of metal and motion. In this moment, watching this tireless automaton, the threat of nuclear annihilation seems almost quaint. Who needs ICBMs when you've got the International Brotherhood of Robotic Stevedores?

But as I stand there, notepad in hand, trying to capture the essence of this mechanical marvel, I can't help but wonder: In this brave new world of metal men and push-button warfare, where do flesh-and-blood humans fit in? And more importantly, who's going to tell the Unimate that, robot or not, it still needs to clock out for smoke breaks?

Welcome to the future, folks. It's shiny, it's efficient, and it doesn't give a damn about the Cuban Missile Crisis.2

Joe leads me deeper into the belly of this mechanical beast, past rows of hunched workers, their faces illuminated by the hellfire glow of welding torches. SPARK! HISS! CLANG! The symphony of industry drowns out the whispers of apocalypse that float in from the outside world.

"So, Joe," I shout over the din, "how'd this metal marvel end up here in little ol' Ewing?"

Joe's chest swells like a proud papa at a Little League game. "Well," he says, "it all started back in '56. Two fellas, George Devol and Joe Engelberger—"

"Let me guess," I interrupt, "they met at a sock hop?"

Joe snorts. "Nah, cocktail party. Get this," he says, leaning in conspiratorially. "Devol and Engelberger, they meet at this swanky cocktail party back in '56. Devol's this inventor type, already got a patent for some 'programmed article transfer' doohickey. Engelberger, he's an engineering hotshot, worked on those fancy jet engines during the war."

Joe pauses for dramatic effect, clearly relishing his role as robot historian. "But here's the kicker - they start yakking about science fiction, 'I, Robot' and all that jazz." He chuckles, shaking his head. "Next thing you know, they're talking shop. Devol's spouting off about flexible automation, Engelberger's seeing dollar signs. BAM! Unimation Inc. is born.3

As Joe talks, I watch the Unimate work. Its movements are hypnotic, a ballet of pistons and gears. Pick up, rotate, place down. Pick up, rotate, place down. No coffee breaks, no cigarettes, no gossip about Marilyn Monroe or whispered worries about fallout shelters.

"But why here?" I ask. "Why not Detroit or—"

"Pittsburgh?" Joe finishes. "Look, mister, we may be a stone's throw from Trenton, but we've got brains here too. GM saw the potential. Hell, they practically stole the thing for 18 grand."

Eighteen grand. The price of progress. Less than the cost of a missile, more than most of these workers will see in a year. I scribble in my notebook, wondering if Thomas Kuhn—that egghead from Berkeley who's got the science world in a tizzy with his talk of paradigm shifts—would see this as a revolution or just another cog in the great machine of progress.4

Somewhere in the distance, a transistor radio crackles to life. The tinny voice of Bob Dylan floats above the industrial cacophony: "The answer, my friend, is blowin' in the wind..."5

But here, in this temple of automation, the answer isn't in the wind. It's in the wires, the circuits, the cold, unfeeling precision of a machine that doesn't know it's making history.

"Say, Joe," I ask, a thought suddenly striking me, "what happens if we go to war? Does the Unimate know how to duck and cover?"

Joe's laugh is as dry as the martinis at last night's fallout shelter planning committee. "Mister, if the bombs drop, this thing'll probably be the only one left standing. Might have to teach it to play chess, though. Gets boring after the apocalypse, I hear."

As we walk back towards the entrance, I can't help but feel a sense of... what? Wonder? Unease? The world outside these walls is balanced on a knife-edge, teetering between annihilation and uneasy peace. But in here, the future marches on, one robotic arm movement at a time.

I think of Rachel Carson's articles I’ve been reading in The New Yorker, of songbirds falling from DDT-laced skies.6 I think of Algeria, newly independent and finding its feet in a world divided.7 I think of Kennedy, pointing to the moon and daring us to dream bigger.8

And I think of this metal worker, this Unimate, tirelessly shaping the world one die-cast piece at a time, blissfully unaware of the drama unfolding around it.

As I leave the plant, the autumn sun bleeds across the sky, painting the GM parking lot in shades of atomic orange and missile-silo gray. A Chevy Bel Air growls to life, its radio blaring the latest from Liverpool—"Love Me Do," they call it, as if love is just another assembly line product.9 In the distance, a flock of geese cuts through the air, V-formation perfect as a squadron of B-52s. Nature's own little cold war, playing out above our heads.

I light a cigarette, inhaling deeply. The smoke mingles with the factory's exhaust, a toxic tango that would give Rachel Carson nightmares. But hey, at least it's not fallout, right? Not yet, anyway.

As I slide behind the wheel, I can't shake the feeling that I've just witnessed... something. Not just a machine, not just a factory, but a glimpse into a world where the lines between man and metal blur like watercolors in the rain. A world where revolutions happen in circuit boards as often as they do in Cuban streets.

I start the engine. Somewhere, a Unimate keeps on working, oblivious to the dreams and fears it's manufacturing along with those die-cast parts. And me? I'm just another cog in the great machine of history, spinning towards a future that's as shiny and uncertain as a freshly minted dime.