The Year Was 2012

And performance became persuasive enough to replace understanding

Welcome, this is A Short Distance Ahead, a weekly series exploring a single year in the history of artificial intelligence. I’m writing 75 essays to mark the 75th anniversary of when Alan Turing posed the question: “Can machines think?” This is essay 62. You don’t need to read these in order; each piece stands alone.

The aim of this newsletter is not to predict the future of AI, but instead to gain perspective on how we got here, while learning how the futures we live with often emerge sideways from the ones we set out to build.

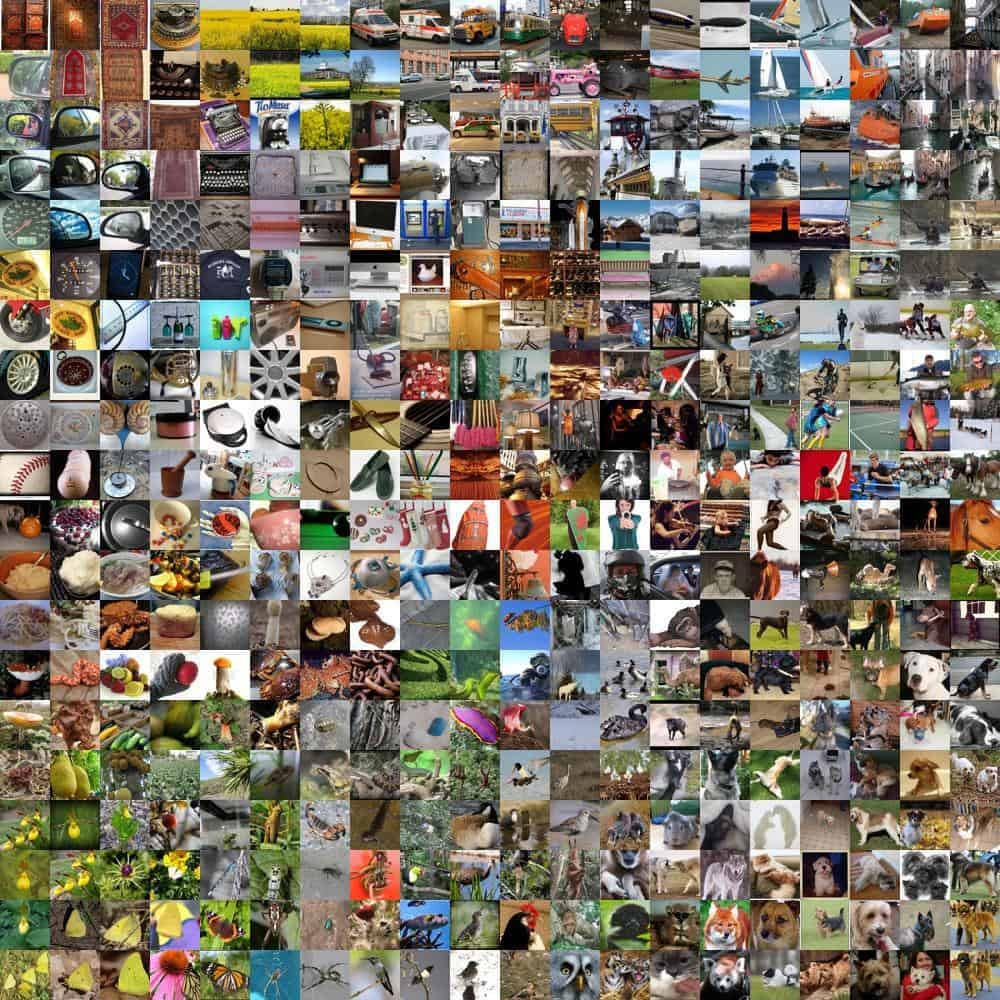

The year was 2012 and Fei-Fei Li was no longer losing sleep over ImageNet.1

By late summer, she had a newborn. Her days were measured in feedings, diapers, and the soft disorientation of a body running on borrowed rest. The project that had consumed years of her life—the ImageNet Challenge, a yearly contest designed to measure how well machines could recognize the contents of images—had slipped into the background of emails she assumed she would answer later.

Then her phone rang.

It was Jia Deng, calling late. Late enough that her first thought was that something was wrong. But his voice didn’t sound alarmed. It sounded animated, confused excitement, the kind that appears when facts don’t yet fit together.

One of the submissions, he said, was behaving strangely.

It was using a neural network.

Ancient, almost.

And it wasn’t just a little better. It was much better. A ten–percentage-point jump over the previous year’s winner. An all-time record. The kind of improvement that wasn’t supposed to happen anymore, not in a field that had settled into careful benchmarks and incremental gains.

Progress doesn’t look like this, she thought.

Or does it?

She booked a flight.

Twenty hours. A blur of time zones. A body that wanted sleep and a mind that refused to slow down. Somewhere over the Atlantic, she opened the slides and stared at the architecture. There was nothing exotic there. No new theory. Convolutions. Layers. Backpropagation. Ideas that had been circulating for decades, often dismissed as impractical or inefficient.2

What had changed wasn’t the math.

It was the scale.

More data than anyone had ever assembled. More computation than anyone had ever applied. Two consumer GPUs (hardware designed to render video games) running nonstop in a bedroom in Toronto, processing image after image, correcting errors again and again until something coherent began to emerge.

Not understanding.

Not meaning.

Performance.

By the time she landed in Florence, it was clear something historic had happened. And almost no one knew it yet.3

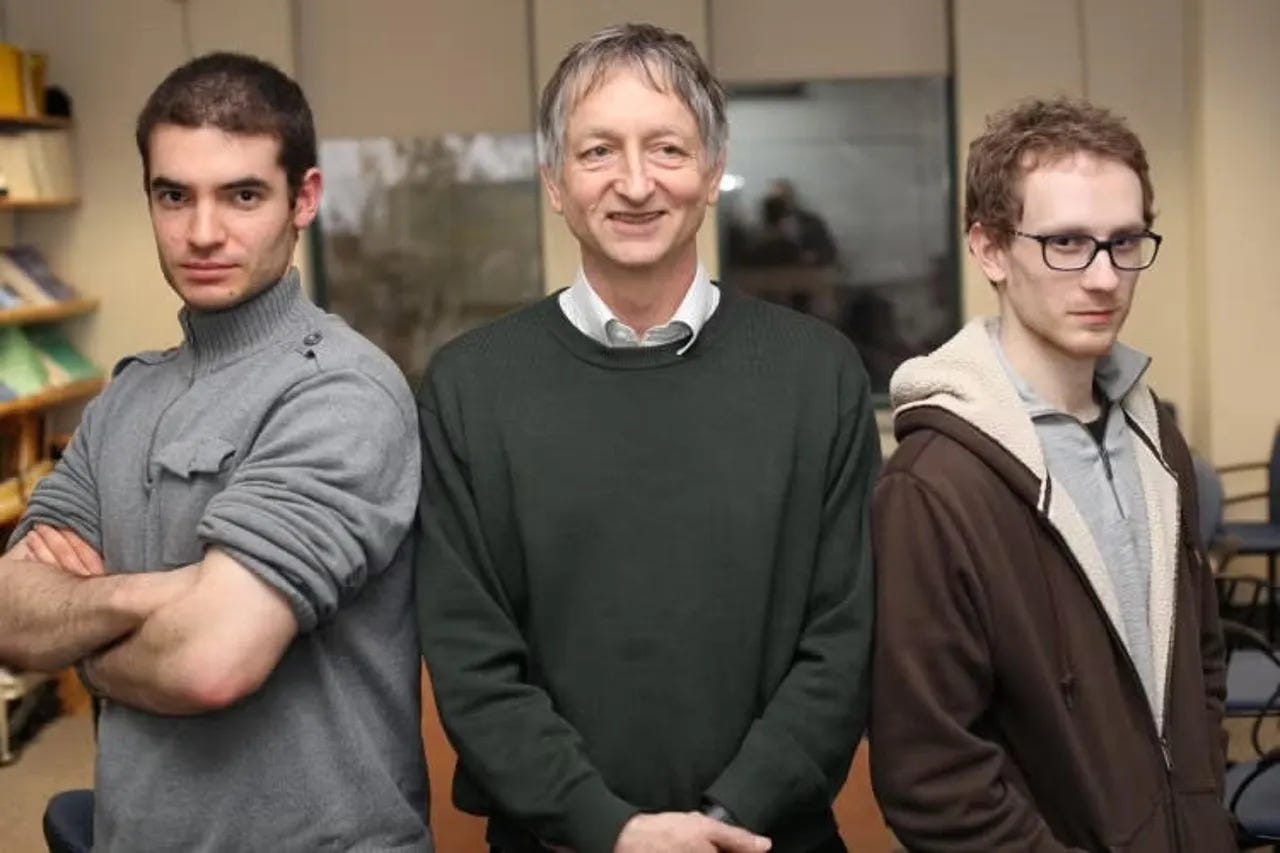

In Toronto, the people behind the system could not have been more mismatched.

Alex Krizhevsky and Ilya Sutskever had both been born in the Soviet Union (Krizhevsky in Ukraine) before their families emigrated, but beyond that shared geography, they could not have been more different.

Sutskever was restless, intense, visibly impatient with anything that felt slow. As an undergraduate at the University of Toronto, he had knocked on Geoffrey Hinton’s4 office door without an appointment, asking, immediately, if he could join the lab. When Hinton suggested scheduling a meeting, Sutskever asked, “How about now?”

Hinton handed him the backpropagation paper—the same one that had unlocked neural networks decades earlier, and told him to come back after he’d read it. Sutskever returned days later. “I don’t understand it,” he said. When Hinton explained that it was basic calculus, Sutskever shook his head. The math wasn’t the problem. The design was. Why weren’t the derivatives fed into a proper optimizer? Why train one network per problem instead of one network that learned many problems at once?

It took Hinton years to reach some of the conclusions Sutskever reached in minutes.

Sutskever joined the lab. His education lagged at first, then caught up at a speed Hinton had never seen. When an idea clicked, Sutskever celebrated by doing handstand push-ups in the middle of the apartment he shared with another student. “Success is guaranteed,” he liked to say.

Krizhevsky was the opposite.

Quiet. Laconic. Less interested in theory than in making things work. He lived with his parents. He hadn’t even heard of ImageNet until Sutskever mentioned it. Where Sutskever and Hinton supplied ideas, Krizhevsky supplied endurance, and an unusual ability to extract speed from machines that weren’t supposed to do this kind of work at all.

Neural networks were still considered finicky. Training them involved what some researchers half-jokingly called a dark art: weeks of trial and error, tweaking numbers you could never calculate by hand, watching systems fail, then fail more gracefully.

Krizhevsky was unusually good at this. Better still, he knew how to push GPU hardware, which was still an oddity in academic labs, to its limits. Every one-percent improvement bought him more time. Hinton joked that each gain earned Krizhevsky another week to finish a long-overdue paper. Krizhevsky took the deal seriously.

In his bedroom, the training ran for days. A black screen filled with white numbers ticking upward. Each week, he tested the system. It fell short. He adjusted the code, tuned the weights, and trained again.5

And again.

By fall, it was nearly twice as accurate as anything else on Earth.

The room in Florence filled quickly.

Krizhevsky clicked through his slides without embellishment. Black-and-white diagrams. Numbers that refused to soften.

People leaned against walls. Others sat on the floor. Skeptics arrived early and stayed late. The objections came fast and familiar. The dataset was too big. The categories arbitrary. The results couldn’t possibly generalize. Someone fixated on T-shirts, as if cotton might be the weak point that brought the whole structure down.

“Krizhevsky didn’t have the chance to defend his work. That role was taken by Yann LeCun6, who stood up to say this was an unequivocal turning point in the history of computer vision. ‘This is proof,’ he said, in a booming voice from the far side of the room. He was right.”7

But, as the discussion went on, the mood changed. Not to consensus, exactly. To something quieter.

Resignation.

A neural network—dismissed for years as inefficient and biologically naive—had just steamrolled the field.

This wasn’t proof in the philosophical sense. It didn’t answer whether machines understood what they were seeing, or whether pattern recognition counted as intelligence.

But it proved something else: understanding was no longer required for performance to be persuasive.

And that was enough.

Understanding was no longer required for performance to be persuasive.

Within months, the question shifted from whether neural networks worked to who would own them.

Emails began to circulate. Meetings followed. Geoffrey Hinton formed a small company, DNNresearch, less to start a business than to give his students a future he couldn’t offer them at the university. Academia didn’t have the money for the machines they now needed. It couldn’t compete for talent that required warehouses of compute and seven-figure hardware budgets.

An auction unfolded from a hotel room in Lake Tahoe. Google. Microsoft. Baidu. DeepMind. Bids climbed into the tens of millions. Hinton hesitated. He liked teaching. He liked Toronto. But his students insisted: this was the moment.

Google won.

What changed wasn’t what we understood, but what we were willing to proceed with—without understanding.

At Google, neural networks stopped being an idea and started becoming a method.

Andrew Ng8 had already been arguing that intelligence scaled with data. Working alongside Jeff Dean, he’d seen what that argument looked like in practice: systems that could run across thousands of machines.

And he understood what that implied beyond Google. Where academia strained under electricity bills, Google barely noticed the cost.

As Hinton arrived, Ng prepared to leave.

That same year, Ng co-founded Coursera with Daphne Koller. His Stanford classes had already escaped the classroom. Now it had a platform. One hundred thousand students became normal. Feedback became instantaneous. Teaching came to look more like optimization.

If neural networks learned by example, so would people.

The class no longer needed the room.

That summer, in Aspen, Colorado, another argument unfolded onstage.

Peter Thiel9—PayPal co-founder, Founders Fund investor, longtime Silicon Valley contrarian—sat across from Eric Schmidt and accused Google of pretending to be something it no longer was. A tech company, Thiel said, didn’t hoard $30 billion in cash. A bank did.

Schmidt laughed it off. Thiel didn’t smile.

This wasn’t really about antitrust. It was about legitimacy. About who got to define innovation in a world where scale had become the deciding factor.

Not everything scaled.

A location-based social app called Loopt quietly failed that year. Its founder, Sam Altman10, had believed he was helping people connect more meaningfully by nudging them—repeatedly—to share their location. Users didn’t want to be nudged. By 2012, only a few thousand people still used the app.

The company sold for just enough to cover its debts.

Altman took the lesson with him, saying: “I learned that you can’t make humans do something they don’t want to do.”11

The systems that survived adapted instead.

Around the same time, Y Combinator12 was refining a different approach.

Fund people in batches. Standardize the terms. Compress years of feedback into months. Let outcomes, not credentials, decide who advanced. It felt informal at first, almost accidental.

Then it kept working.

Outside technology, the same pattern repeated.

A Korean pop song crossed a billion views on YouTube. No translation. No gatekeepers. No explanation. Just circulation, reinforced until the counter rolled over and kept climbing.

On election night in November, Nate Silver refreshed his map. Every state turned out exactly as predicted. The pundits fumed. Silver didn’t argue. He published probabilities and waited for reality to arrive.

Prediction beat persuasion. Again.

By the end of 2012, nothing had been settled philosophically.

Neural networks still couldn’t explain themselves. Models didn’t reveal how they worked, only that they did. Meaning remained contested.

But legitimacy had moved.

Systems were now considered right because they performed. Models earned trust through outcomes, not arguments. What was lost was transparency: how decisions were made, why patterns formed, where responsibility lay when systems failed.

What was gained was speed.

This didn’t mean understanding disappeared. Researchers still debated theory, probed failure cases, argued about meaning.

What changed was that those debates no longer determined what advanced. Performance had become persuasive enough to replace understanding.

Three From Today

One way to see the 2012 shift still unfolding is to look at what happens once scale confers legitimacy. When an aggregator becomes the place users start: Amazon, Spotify, YouTube…Coursera - it stops being just a distributor and becomes the default authority, deciding what gets seen, what gets recommended, what gets priced, and what counts as credible.

Michael B. Horn traces that logic through the proposed, $2.5 billion all-stock merger of Coursera and Udemy. It serves as a reminder that once performance and scale do the persuading, platforms start to look a lot like institutions.

And, the night before Martin Luther King Jr. Day, it’s worth remembering that King’s legacy is often narrowed to what feels comfortable. As Jemar Tisby, PhD explains, ignoring King’s economic vision isn’t accidental….instead it reflects which parts of his legacy we’ve decided are affordable. His post below revisits King not just as a moral voice, but as a sharp critic of inequality, labor exploitation, and economic systems that leave too many behind.

Consider Tisby’s post alongside a conversation from Azeem Azhar of Exponential View with Anthropic’s Head of Economics, Peter McCrory that looks at new data from Anthropic on how AI is actually reshaping work, and where it augments human judgment, where it automates tasks, and where it quietly hollows out the rungs people once climbed to build expertise. It’s an unusually empirical window into how technological progress distributes its gains…and its costs.

Taken together, these pieces ask a shared question across decades: when our tools become more powerful, do we use that power to widen opportunity, or do we optimize systems in ways that make justice feel too expensive to pursue?

The Worlds I See: Curiosity, Exploration, and Discovery at the Dawn of AI, by Dr. Fei-Fei Li, 2023

Genius Makers: The Mavericks Who Brought AI to Google, Facebook, and the World, by Cade Metz, 2022

Genius Makers: The Mavericks Who Brought AI to Google, Facebook, and the World, by Cade Metz, 2022

Supremacy: AI, ChatGPT, and the Race That Will Change the World, by Parmy Olson, 2024