The year was 1999, and humanity was packing its bags for a one-way trip to a new world.

In 1995, exactly seven internet companies had gone public. By 1999, that number had exploded to 249. This wasn't just growth—it was exodus. An entire civilization was abandoning the physical world for digital real estate, and everyone wanted to stake their claim before the land rush ended.1

On CNN that year, viewers watched a young entrepreneur named Elon Musk purchase his first supercar—a silver McLaren F1—with the $22 million he'd made from selling his company Zip2. The transaction itself was unremarkable; what mattered was the medium. Here was new money, made from new rules, being spent on old-world symbols of speed and power, all broadcast through the very networks that were making such wealth possible. The future was buying the past on live television.

As Alessandro Baricco would later observe in The Game, 1999 marked the beginning of humanity's great colonization project…not of distant continents, but of digital space itself. We were mapping new territories, extracting new resources, building new infrastructure, and most profoundly, establishing new forms of intelligence. The colonists weren't conquistadors; they were venture capitalists, hackers, and anyone with a modem and a dream.

Territory Mapping

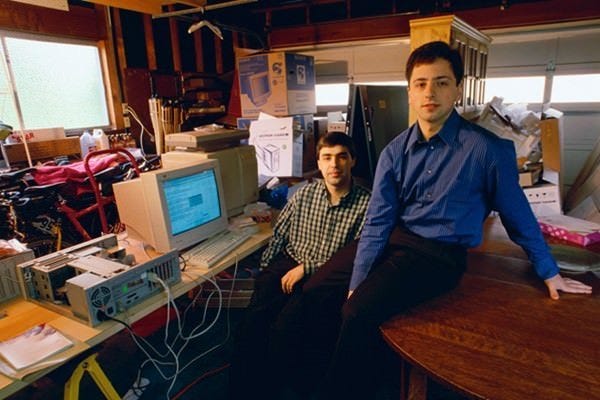

While stock markets were being colonized by dot-com prospectors, Google's Larry Page and Sergey Brin were engaged in a more fundamental act of cartography. Their PageRank algorithm didn't just search the web, it mapped the web's own intelligence, treating each hyperlink as a vote, each connection as a signal of authority and relevance.

This was colonization's first principle: you must map the territory before you can claim it. Page and Brin weren't building a better Yellow Pages; they were creating the Rosetta Stone of cyberspace, teaching machines to read the collective mind of the internet. Their genius wasn't that they knew anything themselves, but that they knew how to interpret what everyone else knew.

Resource Extraction

But the most audacious act of digital colonization began in a Northeastern University dorm room, where nineteen-year-old Shawn Fanning was about to turn culture itself into a natural resource.

"As technologists, as hackers, we were sharing content, sharing data all the time," recalled Jordan Ritter, Napster's founding architect. "If we wanted music, we would go into some IRC channel, and hit up a bot there and download music from it. It was still kind of a pain in the ass to get that stuff. So Fanning had a youthful idea: Man, this sucks. I'm bored, and I want to make something that makes this easier."

The most casual declaration of war on an entire industry ever uttered.

When Eileen Richardson, Napster's early CEO, first downloaded the software, she found herself literally shaking. "Oh my god, oh my god," she remembered thinking. This was Paul Revere realizing the British were coming, except she was realizing the future had arrived.

Elizabeth Brooks, Napster's VP of Marketing, went up to the server room with a stopwatch to count files flying back and forth. "We realized the scope of the business because the number was just astronomical. Billions of songs a month, and this was early on. Realizing that you're really in a game-changing moment—that's the happiest feeling anybody who's committed to innovation can have."

This wasn't just file sharing; it was the complete redistribution of cultural wealth. Sixty million people suddenly discovered they didn't need record stores, radio stations, or the entire apparatus of music distribution. Chuck D of Public Enemy called Fanning "the one-man Beatles" and declared Napster "one of the most revolutionary things ever done in music, period."

The confrontation was inevitable. When RIAA president Hilary Rosen called Richardson to complain about copyright infringement, Richardson asked which copyrights specifically. "Open up Billboard magazine!" Rosen snapped. "The top 200 are right there!" Richardson's response was pure colonial defiance: "I'm sorry. I don't subscribe to Billboard magazine."

The day the injunction came down, Richardson's BlackBerry literally died from the volume of support emails—10,000 messages in a minute, the device vibrating itself to death on her desk. Even the old communication infrastructure couldn't handle revolutionary fervor.2

Population Transfer

That March, The Matrix arrived in theaters, and suddenly the great migration from physical to digital didn't feel optional—it felt inevitable. The Wachowskis had given humanity its founding myth for the digital age: we were already living in a simulation, we just hadn't realized it yet.

The film's timing was perfect. As millions of people were learning to shop online, bank online, and date online, The Matrix suggested that online was where we'd always been. The red pill wasn't a choice between reality and illusion—it was a choice between comfortable digital servitude and uncomfortable digital awareness.

Infrastructure

But even as we rushed headlong into our digital future, we couldn't escape our analog past. Y2K loomed like a judgment day, threatening to reveal just how completely we'd already migrated our civilization into machines that might forget how to count past 1999.

The panic wasn't really about computers failing; it was about realizing how completely we'd already entrusted our lives to systems we barely understood. Power grids, banking networks, air traffic control—all running on code written by programmers who'd never imagined their work would still be running at the turn of the millennium.

Companies spent $600 billion preparing for Y2K, the largest peacetime mobilization in human history. We were debugging our own migration to digital dependency, one line of legacy code at a time.

Intelligence Networks

While 249 companies colonized digital marketplaces, AI researchers were colonizing something far more intimate—the architecture of thought itself.

David Waltz, in his presidential address to the American Association for Artificial Intelligence, declared that importance itself was the foundation of intelligence. Not logic, not reasoning, but the emotional capacity to discern what matters. "Real intelligence," he argued, hinged on biological needs and survival instincts that AI had completely overlooked in its obsession with symbolic reasoning.

Meanwhile, Tomaso Poggio and Christian Shelton were mapping biological vision onto silicon, teaching machines to see by studying how brains processed visual information. They weren't just building better cameras; they were reverse-engineering the miracle of perception itself.

The "Automated Learning and Discovery" conference revealed researchers training machines to explore and claim new knowledge territories on their own—digital natives venturing into intellectual wilderness their human creators couldn't map. And workshops on "Distributed Data Mining" showed how intelligence networks could span multiple databases, multiple locations, creating cognitive infrastructure that existed everywhere and nowhere simultaneously.

This was deeper colonization than moving our shopping online. We were outsourcing the work of thinking itself to our digital colonies, teaching machines not just to compute, but to care about what mattered.

The New World

As 1999 drew to a close, Jensen Huang stood in NVIDIA's offices, looking at chips that would either save his company or destroy it. "Our company is thirty days from going out of business," he regularly reminded his employees—a ritual that had become grimly familiar. They had just enough cash for a single month's payroll.3

But Huang had gambled everything on an untested batch of silicon called the GeForce GPU. "It was fifty-fifty," he later admitted, "but we were going out of business anyway." While the world worried about whether old systems would survive Y2K, Huang's team was betting their lives on an entirely new way of computing—parallel processing that could render virtual worlds pixel by pixel.

They called it the Graphics Processing Unit, though none of them could have predicted it would become the computational engine for cryptocurrency mining, artificial intelligence, and neural networks that would eventually learn to paint, write, and reason. In 1999, it was just thirty desperate days between NVIDIA and bankruptcy, solved by silicon that could make Quake run faster.

The colonization was complete, though most of us wouldn't realize it for years. We'd built new territories in cyberspace, extracted new forms of value from information itself, migrated our commerce and culture to digital platforms, and begun training artificial intelligences to think on our behalf. The hardware to power it all had been created by a company that was perpetually thirty days from death.

Alessandro Baricco was right: 1999 was when we entered “The Game.” But unlike previous colonial projects, this one didn't require us to leave home. Instead, it brought a new world to us, pixel by pixel, protocol by protocol, until the boundary between physical and digital dissolved entirely.

The year 2000 was just a short distance ahead, and we were no longer the same species that had worried about running out of calendar pages. We were digital natives now, citizens of a country that existed everywhere and nowhere, ruled by algorithms we'd written but could no longer fully understand.

The colonization was complete. The question was: who had colonized whom?

Thanks for reading A Short Distance Ahead, a weekly exploration of artificial intelligence’s past to better understand its present, and shape its future. Each essay focuses on a single year, tracing the technological, political, and cultural shifts that helped lay the foundation for today’s AI landscape.

If you're a new reader, welcome. For context, I'm exploring the creative process of narrative design and storytelling by drafting these essays in tandem with generative AI tools, despite deep concerns about how algorithmic text might dilute the human spirit of storytelling. By engaging directly with these tools, I hope to better understand their influence on creativity, consciousness, and connection. I also write elsewhere without AI assistance and I’m at work on my first collection of short stories. If you find value in this work, please consider sharing it or becoming a subscriber to support the series.

As always, sincere thanks for your time and attention.

How the Internet Happened: From Netscape to the iPhone, by Brian McCullough

Ashes to ashes, peer to peer: An oral history of Napster, Richard Nieva, Fortune, September 5, 2013 (paywall)

How Jensen Huang’s Nvidia Is Powering the A.I. Revolution, by Stephen Witt, The New Yorker, November 27, 2023

Does every generation hope for the novel change taking place in their lifetime to give them an opportunity to stake their claim to the future? Are all paradigmatically novel changes in society created equal? The internet expanded the surface area on which commercial value could be created more so than any previous. More so than the doctrine of underwriting? More than the plough? The internet also allowed a level of financialisation we'd never seen before... dragging hypothetical value from the future into the present as actual value in cash and cars and equities. The printing press can't hold a candle to that.

Love this - i wonder if you could have gone more into about the tension people felt with these new changes? I was too young to know this, but I imagine there was a tension/excitement with the new century and what would it look like?