Welcome to A Short Distance Ahead, a weekly exploration of artificial intelligence’s past to better understand its present, and shape its future. Each essay focuses on a single year, tracing the technological, political, and cultural shifts that helped lay the foundation for today’s AI landscape.

If you're a new reader, welcome! For context, I'm exploring the creative process of narrative design and storytelling by drafting these essays in tandem with generative AI tools, despite deep concerns about how algorithmic text might dilute the human spirit of storytelling. By engaging directly with these tools, I hope to better understand their influence on creativity, consciousness, and connection. I also write elsewhere without AI assistance and I’m at work on my first collection of short stories. If you find value in this work, please consider sharing it or becoming a subscriber to support the series.

Quick housekeeping note: This is essay #45 of our 75-part journey leading to the 75th anniversary of Alan Turing’s seminal October 1950 paper. I’ve missed the last two weeks, but have decided to keep our chronological order rather than combining years. This means our final essay will appear later in November than originally planned.

The year was 1996, and two laboratories—one filled with computer screens, the other with test tubes—were pushing the boundaries of what we considered life. In Scotland, Dolly the sheep made global headlines as the first cloned mammal, while in a modest office outside London, Steve Grand's digital creatures were capturing the imagination of a smaller but no less passionate audience of players, philosophers, and AI researchers.

In London, Steve Grand was teaching digital creatures that could learn and adapt. His software program, "Creatures," released that summer by Millennium Interactive, introduced players to Norns—adorable, big-eyed beings who existed entirely in the digital realm. But unlike the pixelated characters in other games, these creatures weren't just animations following predetermined paths. They were, in Grand's mind, almost alive.

"Life is not made of atoms," Grand would later write, "it is merely built out of them. What life is actually 'made of' is cycles of cause and effect, loops of causal flow. These phenomena are just as real as atoms — perhaps even more real. If anything, the entire universe is actually made from events, or which atoms are merely some of the consequences."1

His Norns possessed simulated biochemistry, digital neurons, and gene-driven behavior patterns. They learned to speak, displayed emotions, and, most strikingly, they died. Not because Grand programmed death as an event, but because the cascading patterns of their virtual biochemistry simply ceased to maintain themselves, like a wave that finally collapses back into the ocean.

When they died, real humans wept real tears. Online forums filled with digital funerals. One player wrote: "I know it's just a program, but I miss her." Some players even reported their creatures appeared in dreams, asking to be fed or played with.2

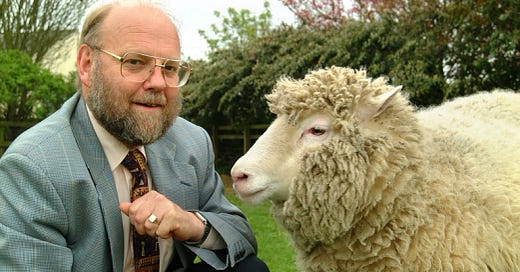

Meanwhile, in a laboratory in Scotland, scientists at the Roslin Institute were also disrupting conventional notions of life. On July 5th, they successfully birthed a lamb they called Dolly, the first mammal cloned from an adult cell. Looking at her, you would see an ordinary sheep. But Dolly represented something extraordinary: proof that specialized cells could be reprogrammed to restart the cycle of life, that biological destiny wasn't irreversible.

The scientists who created her had extracted a cell from a six-year-old ewe's mammary gland, fused it with an egg cell stripped of its nucleus, and implanted the resulting embryo into a surrogate mother. The process sounded like science fiction, yet there Dolly stood, a woolly testament to human ingenuity, blinking in the camera flashes.

Dolly grazed in fields, breathed grass-scented air through lungs that were perfect copies of another sheep’s lungs. Her creators did not expect her to live a normal lifespan; indeed, Dolly died at just six years and seven months, half the typical life expectancy of her breed. After her death, her body was displayed at the National Museum of Scotland, where visitors can still see her today, stuffed and mounted behind glass.

These twin developments—one in bits, one in cells—emerged simultaneously into public consciousness. Both questioned the boundary between "real" and "artificial" life. Both suggested that life was less a matter of substance and more a pattern that could be reproduced, transferred, preserved. And both triggered profound questions about what comes next when humans gain the power to create life.

Players of Creatures found themselves unexpectedly moved when their digital Norns died. Online forums filled with messages of grief and remembrance for beings that, in a technical sense, had never been alive. "I actually cried when my first Norn died," wrote one player. "I know it sounds ridiculous, but I'd become attached." The emotional attachment was precisely what made Grand's experiment so remarkable, these weren't just characters in a game; they were patterns that persisted, learned, and evolved until, finally. . .they didn't.

Dolly, meanwhile, faced scrutiny of a different kind. Newspapers around the world announced her birth with equal parts wonder and alarm. "Will humans be next?" asked headlines, as ethicists, religious leaders, and scientists debated the implications. That she was cloned from a mammary gland cell led to her being named after Dolly Parton, a joke that underscored how unprepared society was to grapple with the philosophical questions her existence raised.

In 1996, these weren’t the only events bumping up against the boundaries between human and machine intelligence, between "found" and "created" life. In February, IBM's Deep Blue defeated chess grandmaster Garry Kasparov in a single game, though Kasparov would win the match overall. The machine's victory, limited as it was, sent a ripple of reckoning through the world of competitive chess and prompted deeper inquiries into whether strategic thinking—once considered uniquely human—could be replicated by silicon and code.

That August, NASA scientists announced they had discovered possible microscopic fossils in a Martian meteorite designated ALH84001. President Bill Clinton addressed the nation about the finding, calling it "stunning" and promising to "put its full intellectual power and technological prowess behind the search for further evidence of life on Mars." The announcement momentarily expanded our conception of where life might emerge or have emerged.

Even as these boundary-blurring developments unfolded, Congress passed the Telecommunications Act of 1996, fundamentally restructuring how information would flow in the coming digital age. The legislation, which President Clinton called "truly revolutionary," deregulated the telecommunications industry and inadvertently set the stage for the internet's explosive growth. That same year, Neal Stephenson chronicled the physical laying of FLAG (Fiber-optic Link Around the Globe) in WIRED magazine, revealing the massive undersea cables that would become the backbone of our digital world—the very medium through which both digital life and news about biological breakthroughs would eventually propagate.

In the realm of philosophy, David Chalmers published "The Conscious Mind," formalizing what he called "the hard problem" of consciousness—the question of how physical processes in the brain give rise to subjective experience. His work would become central to discussions about whether digital beings like Grand's Norns could ever be considered truly conscious, or if consciousness remained an exclusively biological phenomenon.

As 1996 drew to a close, both Grand's digital creatures and Dolly the sheep continued their quiet existences, unaware of the philosophical earthquakes they had triggered. Grand kept refining his artificial life systems, convinced that truly intelligent machines would emerge not from rule-based programming but from self-organizing patterns that mimicked life's fundamental processes. The scientists at Roslin Institute continued their work on mammalian cloning, gradually improving techniques that would eventually contribute to stem cell research and regenerative medicine.

The twin revolutions of 1996—artificial life and biological recreation—marked humanity’s first real attempts to occupy roles once reserved for nature or the gods. Yet both efforts offered only incomplete metaphors for life: Grand’s creatures had no bodies, and Dolly, for all her biological authenticity, was still just a copy—not a true creation.

Neither lab had yet achieved what philosophers call “strong emergence,” the mysterious leap by which consciousness arises from complexity. But both had taken early steps toward a new view of life—not as a state of matter, but as a pattern of information, a wave rather than a particle, capable of manifesting in either silicon or cells. And so, as 1997 approached, a new question quietly incubated alongside these experiments: not whether we could create life, but whether we’d recognize it when we did.

One final housekeeping note:

I've always wanted to keep these weekly essays accessible—allowing you to dip in and out without missing crucial context, though I recognize they can get dense. To improve this, I’m streamlining essay lengths and separating out the Two From Today section that previously concluded each essay.

This section highlighting recommended AI-related reading will become a separate bi-weekly curated post for paid subscribers only, as it requires additional time beyond what I currently allot for the weekly essays.

My goal is not to create another AI news tracker (see my resources page for some links to my favorites, or

’s recent list of AI newsletters.) Instead I’ll offer nuanced curation of articles that echo our historical themes, and sometimes themes related to the process of writing in the age of AI (more to come on this as well.) Most will be current, but some maybe older, yet particularly relevant.I’ll share the first few editions with all subscribers so you can decide if they’re worth the price of a monthly fancy latte or cheap beer.

This marks my first real attempt at growing this newsletter beyond its organic roots. Please bear with me as I navigate Substack's subscription methods with some healthy wariness.

I hope that by giving this newsletter more of my time and attention, it can continue to evolve from a fun experiment into something even more valuable to you all.

As always, I’m grateful for your time and attention. Thank you.