Welcome to A Short Distance Ahead where we explore artificial intelligence’s past in an attempt to better understand the present and future. In each essay, I'm examining a singular year’s historic milestones and digital turning points, tracing how these technological, political, and cultural shifts laid groundwork for today's AI landscape. Technically this is last Sunday’s newsletter — delayed. Sorry. The next essay, “The Year Was 1994,” will be back on track for this Sunday night.

Also, I recently added a few sentences to the About page explaining my thoughts on the process of co-writing these essays with AI. I thought it was worth sharing up front here, and will be included in summary ahead of each essay going forward.

A Note About My Process

I've embarked on the process of co-writing with AI as an experiment. In full disclosure, I have deep concerns about using these tools for creative purposes. Especially as someone who believes "we need fiction like we need water" — that stories flowing from unique human perspectives are essential nourishment for our consciousness. Lewis Hyde argues in The Gift that creative work is fundamentally different from commodity exchange — it's a gift that carries the spirit of the giver, creating connections between humans that transcend transaction. When we substitute or dilute this gift with algorithmically-generated text, we may risk losing the very essence that makes storytelling a sacred transmission of human experience.

I believe there is something fundamental that happens in our brains when we attempt to ‘extract’ the very personal waves of creative expression that flow within our ‘hearts and minds’ onto a blank page, blank canvas, etc. I am troubled by the potential effects that replacing that fundamental act of creative expression, or even by altering it slightly, will have on our minds, emotions, and collective creative consciousness.

But, I’ve come to believe the best way to be prepared for contemplating, defending, and discussing these concerns requires active engagement with these technologies. Ultimately, this is a deeper, more nuanced topic I hope to explore in greater depth in the Paid Subscriber tiers of this newsletter, where I will also be sharing more details on my process of writing with these technologies and tools. Stay tuned.

Last, if you find value in these historical explorations, please consider sharing with others who might appreciate this perspective, or becoming a paid subscriber (costs about the same as one fancy coffee drink a month) to support this work. As always, I'm grateful for your time and attention.

The year was 1993, and the world was learning to compress.

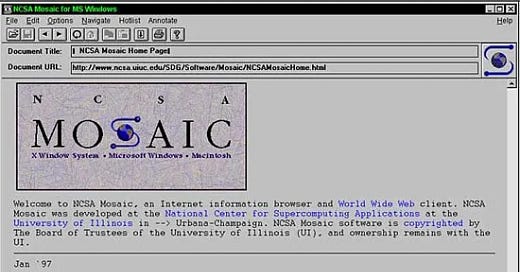

In a university laboratory in Illinois, Marc Andreessen was removing obstacles. Each line of code he wrote for what would become the Mosaic web browser was an act of erasure – wiping away the technical barriers that had kept the average person from accessing the World Wide Web.1 Before Mosaic, navigating the digital landscape required specialized knowledge, command-line interfaces, and a willingness to get lost in the brambles of technical syntax. After Mosaic, you just…pointed and clicked.

"Let me take that away for you," Mosaic seemed to say to the world. "You shouldn't have to worry about HTTP protocols or HTML formatting. Just click the blue words and go."

Meanwhile, in Germany, the Fraunhofer Society's audio engineers were also in the business of removal. The algorithms they perfected for what would be called MP32 systematically stripped away the parts of sound that human ears couldn't perceive. What remained was still recognizably music – the ghost of the original – but leaner, more portable, more liquid.

"Sound should travel like water," they might have said, had they been poets instead of engineers. "It should flow anywhere, into any vessel."

These twin inventions – Mosaic and MP3 – weren't just technological advances. They were manifestations of a new mentality that prized movement above all.3 The MP3's ruthless compression made sound files small enough to move across early networks. Mosaic's intuitive interface made the act of moving through digital space accessible to anyone who could operate a mouse. Together, they revealed the same underlying philosophy: anything that impedes motion must be removed.

This was not coincidental. The Berlin Wall had fallen just four years earlier. NAFTA was being signed that very year, dissolving economic barriers between the United States, Canada, and Mexico. The Maastricht Treaty was creating the European Union, merging distinct markets into a unified whole. Everywhere you looked, borders were becoming more permeable, walls were coming down, and separate entities were flowing into one another.

Bill Clinton, who took office that January, embodied this new dynamic perfectly – the first Baby Boomer president, raised on rock and roll, comfortable with technology in a way his predecessors had never been. When he insisted that "there is nothing wrong with America that cannot be cured by what is right with America," he was expressing the same self-referential logic that allowed the web to be both content and container, both message and medium.

What no one fully understood in 1993 – not the engineers, not the politicians, not even the visionaries – was that they were building the infrastructure for an entirely new way of being. The compression algorithms that made MP3s possible would eventually be applied to images, video, and ultimately to human expression itself. The point-and-click interface pioneered by Mosaic would evolve into touchscreens, voice commands, and eventually the seamless human-computer interactions that power modern AI.

The newly founded company Nvidia was working on graphics processors that would, decades later, become the computational engines behind the deep learning revolution.4 But in 1993, they were just trying to render video game graphics more efficiently – another form of compression, another way to remove obstacles to movement.

As Bill Clinton and Al Gore promised an "information superhighway" and South Africans Nelson Mandela and F.W. de Klerk accepted the Nobel Peace Prize for dismantling apartheid's rigid structures, the digital pioneers were quietly building a world where information would flow as freely as capital across the newly borderless European Union.

Mosaic's blue hyperlinks and MP3's invisible compression algorithms were the first drops of what would become a flood – a torrent of bits and bytes moving at the speed of light, carrying human knowledge, human art, human thought across distances that would have seemed magical just years before.

And yet, beneath their shared devotion to movement, they embodied opposite impulses. MP3 was about compression – making the world smaller, more portable, reducing reality to its essential elements. Mosaic was about expansion – opening doors to new spaces, creating boundless exploration, turning the finite screen into an infinite canvas. One squeezed the world tight enough to fit in your pocket; the other stretched your pocket until it could contain the world. This tension between compression and expansion would become a defining dynamic of the digital age – the constant push to make things smaller, faster, more efficient, paired with the equally constant pull to make experiences richer, more immersive, more connected.

The Battle of Mogadishu that October showed the limits of American military power in a world that was becoming more interconnected but not necessarily more peaceful. The bombing of the World Trade Center earlier that year demonstrated that malevolence, too, could flow across borders. But these were seen as aberrations, temporary obstacles to the grand project of setting everything into motion.

In this nascent digital landscape, no one was thinking about artificial intelligence as we understand it today. The AI winter still gripped academic research, with rule-based expert systems having failed to deliver on their promises. But the seeds were being planted. By making information more liquid, more compressed, more mobile, the innovations of 1993 were creating the necessary conditions for the vast datasets and processing power that would eventually feed deep learning algorithms.

As the year drew to a close, most people were still using dial-up modems, still purchasing music on CDs, still watching broadcast television. But the direction was clear. The world was being compressed, digitized, set into perpetual motion. The mental revolution had already happened; the technological revolution was just catching up.

And in the gaps between the ones and zeros, in the sounds that MP3 discarded and the interfaces that Mosaic simplified, a new kind of intelligence was waiting to be born – one that would eventually learn to compress not just sound and images, but reality itself.

As if sensing this approaching future, a computer scientist named Vernor Vinge presented an updated version of an earlier paper at NASA's VISION-21 Symposium that very year, later published in Whole Earth Review. In it, he coined a term for the moment when technological advancement would accelerate beyond human comprehension: "the Singularity." While Mosaic users clicked their blue links and music enthusiasts debated the merits of digital compression, Vinge was quietly prophesying: "Within thirty years, we will have the technological means to create superhuman intelligence. Shortly after, the human era will be ended."

Few paid attention to his warning in 1993. They were too busy marveling at their newfound ability to flow across digital spaces, to compress and expand at will, to set everything in motion. The mental revolution had already happened; the technological revolution was just catching up. And the singularity? That was still a short distance ahead.

Three From Today

First, Hayao Miyazaki famously condemned generative AI as "an insult to life itself," yet OpenAI's new image generation feature recently sparked controversy by enabling users—including CEO Sam Altman—to create viral "Ghiblified" images in Studio Ghibli's distinctive style without the studio's consent. The incident highlights ongoing ethical and copyright tensions around AI-generated art, underscoring artists' concerns about exploitation and cultural devaluation, but it also gets at something deeper. As

writes inSecond, a new paper claims that LLMs have finally "passed" the Turing Test, reigniting familiar hype—but, as

argues, the test remains fundamentally flawed because it measures human gullibility rather than true machine intelligence. Marcus emphasizes that today's systems are still essentially advanced mimicry tools, lacking genuine reasoning or common sense.And last, but today The New York Times published an encouraging article on the movement to ban cell phones in schools in the UK. A topic I wrote about a few weeks ago in my profile of

for The Philadelphia Citizen. You can read the Times article gifted here:The U.K. Government Wouldn’t Ban Phones in Schools. These Parents Stepped Up.

See The Game: A Digital Turning Point by Alessandro Baricco

This tension between compression and expansion...never thought of technology in such a binary way. Strikes me that conscienceness of this energy, or said another way, when in a flow state, that tension dissipates.