Welcome to 1991. As a reminder, Short Distance Ahead is a reader-supported project and I believe in keeping it accessible to everyone. If you find value in my work and can afford to contribute, subscriptions are $8/month or $80/year. Your support, at whatever level works for you, makes this work possible. Thank you.

The year was 1991, and in a small office in Hunt Valley, Maryland, a soft-spoken midwesterner with the affect of a high school science teacher was building entire worlds from scratch.

Sid Meier didn't set out to create one of the most influential strategy games of all time. The genesis of Civilization began, rather mundanely, over lunch. Meier and his colleague Bruce Shelley had developed a habit of playing board games during their breaks at MicroProse, the company Meier had co-founded in 1982. Between bites of sandwiches, they'd wage war across cardboard continents, build railroads, and establish trade routes.

"Bruce and I played a lot of board games," Meier would later recall. "Railroad Tycoon was inspired by 1830, an Avalon Hill railroad board game. But perhaps even more influential was the computer game Empire, a conquest game created by Walter Bright in the 1970s that Meier had played extensively. These influences—both physical board games and early digital strategy games—would shape Civilization's development.1

After the success of Railroad Tycoon, Meier approached MicroProse's other co-founder, Bill Stealey, with his next idea. "I'm going to do a game about the history of civilization," Meier said. Stealey, a former Air Force pilot who preferred flight simulators to strategy games, was skeptical about the concept’s commercial appeal. According to industry lore, he was concerned that a turn-based strategy game might not find an audience in a market dominated by action and simulation titles.

Meier pressed on anyway. Working with designer Bruce Shelley, he began building a game that would let players guide a civilization from the Stone Age to the Space Age. Unlike the real-time strategy games that dominated the market, Civilization would be turn-based, giving players time to consider their options. Meier wanted every click to represent what he called "a series of interesting decisions," not tests of reflexes or dexterity.

As Meier and Shelley refined their digital sandbox through 1991, the actual world outside their office windows was undergoing its own series of interesting transitions. The Cold War was ending not with nuclear annihilation but with a whimper. The Warsaw Pact officially dissolved in July. The Soviet Union itself would cease to exist by December.

In Iraq, Operation Desert Storm demonstrated how technological superiority could determine military outcomes, as precision-guided munitions and night-vision equipment gave coalition forces an insurmountable advantage over Saddam Hussein's more numerous but less advanced military. The concepts of "tech trees" and "technological advantage" that would form the backbone of Civilization's gameplay were playing out in real time on CNN.

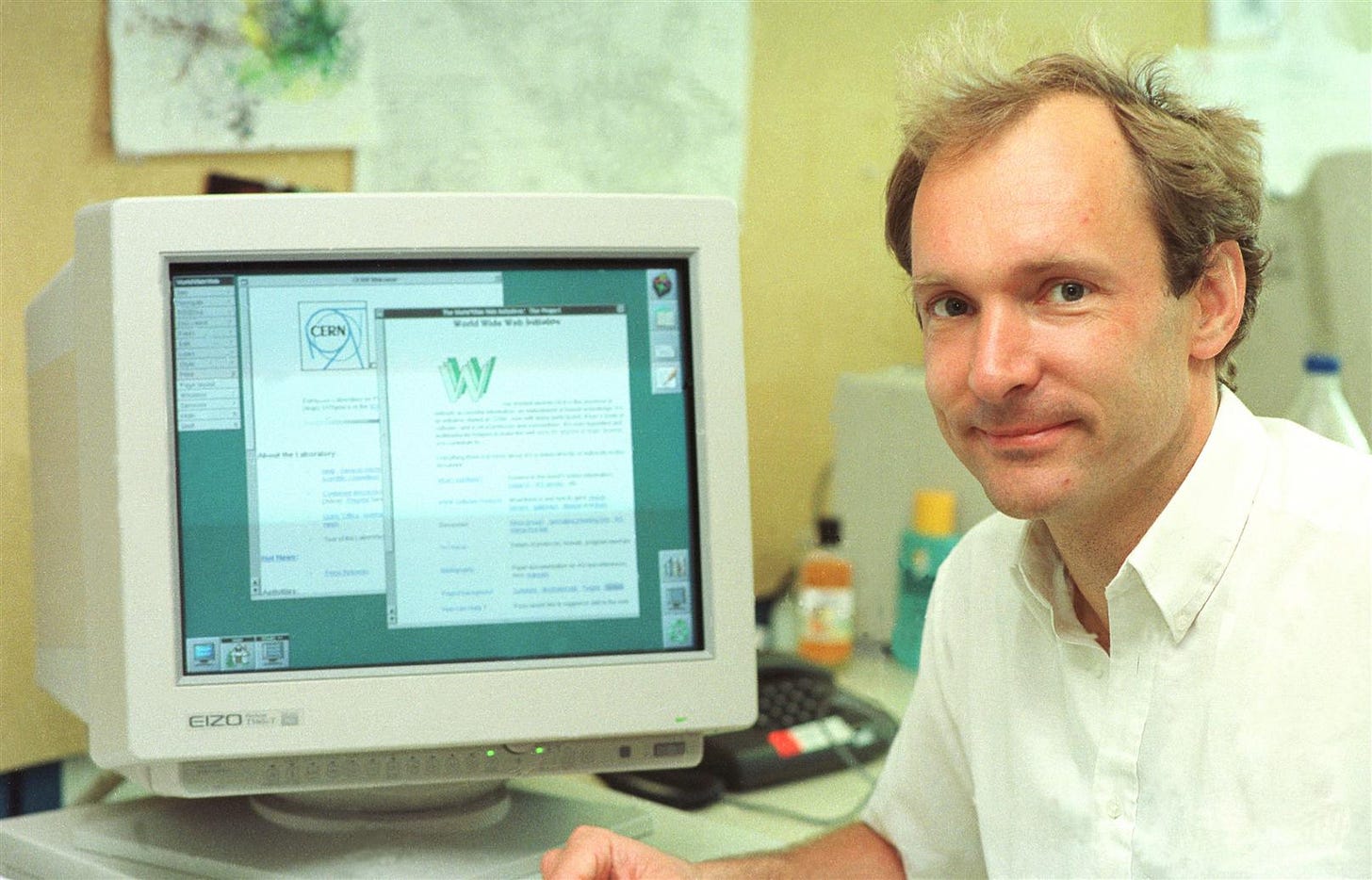

Meanwhile, as Meier was coding a tech tree that included "Computing" and "The Internet" as late-game technologies, Tim Berners-Lee published the first website at CERN, introducing the World Wide Web to the public in August 1991. Few could have predicted how this innovation would transform global society in the coming decades, but Civilization players would soon understand the game-changing power of a well-timed technological breakthrough.

Once the game began taking shape, play testers quickly discovered its dangerously addictive quality. "Just one more turn" became the game's unofficial tagline among players—a phrase that would become synonymous with the series as gamers found themselves unable to stop playing, even as the clock ticked toward dawn. The game had a way of keeping players perpetually on the hook, always with another city to build, technology to research, or wonder to construct just a few turns away.

This captivating quality stemmed partly from the game's brilliant pacing. Early turns moved quickly, with players making simple decisions about where to build cities or which basic technologies to research. But as civilizations grew more complex, so did the decisions. By the game's middle stages, players were juggling diplomatic relations, resource management, military strategy, and technological research. The game's genius lay in its gradual introduction of complexity—by the time players were managing sprawling empires, they had internalized the game's systems so thoroughly they hardly noticed the cognitive load.

Civilization presented a particular vision of human development, one that followed a Western-centric, technology-driven path. The game framed history as a competition between civilizations where progress was inevitable and measurable. This perspective wasn't universal, of course, but it reflected the triumphalist mood of post-Cold War America. Francis Fukuyama had published "The End of History?" in 1989, arguing that Western liberal democracy represented the endpoint of humanity's sociocultural evolution. Civilization encoded this perspective into its victory conditions and underlying assumptions.

In the game, players could choose to lead one of several historical civilizations, each with slight advantages but fundamentally following the same path of development. The Romans might excel at building roads, the Americans at government, but all were measured against the same metrics of success: technological advancement, territorial expansion, and eventually, the construction of a spaceship to Alpha Centauri.

The game's mechanics encoded certain values and assumptions: progress is linear and technological; history is driven by "great men" (each civilization has a male leader except for Elizabeth I); expansion and growth are inherently good; domination of resources and territory is natural. The original game offered just two paths to victory: complete military conquest or winning the space race by building a spaceship to Alpha Centauri. Even this binary choice reflected a Cold War mindset—players could dominate through military might like the Americans or achieve scientific triumph like the Soviets with their Sputnik moment, though the game emerged just as this decades-long competition was ending.

As autumn arrived in 1991, Meier and his team were racing to finalize the game for its November release. The world outside continued its own fascinating turn sequence. In September, Nirvana released "Nevermind," signaling a cultural paradigm shift that would define the decade. Linux kernel was first released by Linus Torvalds, demonstrating how open-source development could paralleled mainstream computing.

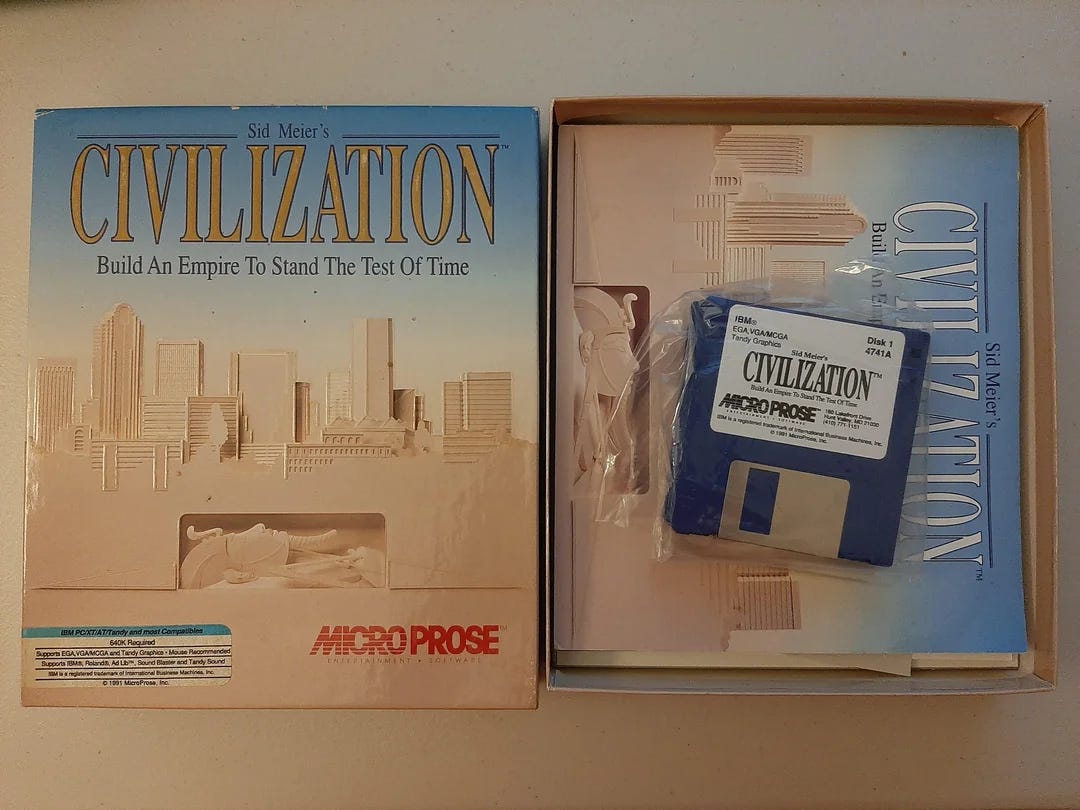

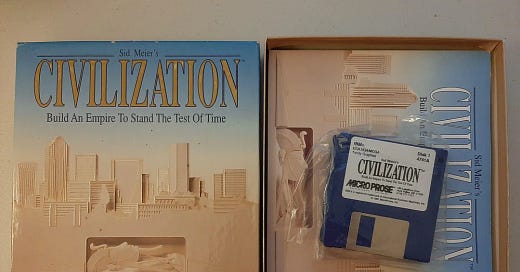

Civilization finally launched in November 1991, with little fanfare or marketing push. Its box featured a stone-faced Sumerian ruler against a background of pyramids, sphinxes, and satellites—a visual summary of the game's ambitious historical scope. There were no television commercials, no launch parties. The game simply appeared on store shelves, its ambitions belied by its modest packaging.

And yet, something remarkable happened. People started playing. And they couldn't stop.

Reviews were ecstatic. Computer Gaming World called it "the best program of its type created for the computer." Word of mouth spread among strategy gamers. Sales, initially modest, grew steadily. Unlike most games, which saw their sales peak in the first few weeks and then decline, Civilization built momentum over time.

The game's cultural impact extended far beyond entertainment. Some players reported learning more history from the game than from school. Others, including future tech entrepreneurs, absorbed its lessons about resource management, technological development, and strategic planning.

In 1991, as the Soviet Union collapsed on Christmas Day, the first copies of Civilization began finding their way onto store shelves and into the hands of eager players.

In 1991, as Magic Johnson announced he had HIV, changing public perception of the epidemic, players discovered their cities could be ravaged by plagues if they neglected public health.

In 1991, as the first text message was sent, players researched "Electronics" in pursuit of the powerful "Computers" technology.

In 1991, as Space Shuttle Atlantis deployed the Compton Gamma Ray Observatory, players raced to collect the components necessary to launch their own Alpha Centauri missions.

In 1991, as a New World Order emerged following the Gulf War, players learned that history favored those with technological advantages and resource control.

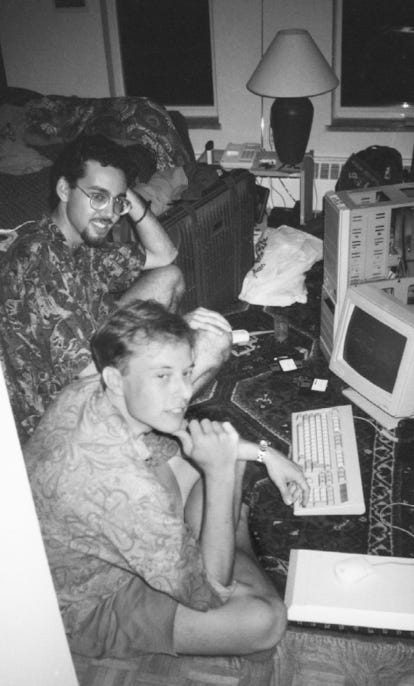

In 1991, at Queen's University in Kingston, Ontario, a 20-year-old South African transfer student named Elon Musk moved his desk so he could sit on his bed while his roommate Navaid Farooq sat on a chair, the two of them facing off to play Civilization for hours until exhaustion overtook them.2

"We completely entered a zone for hours," Farooq would later recall.

After these marathon sessions, over meals in the dining hall, Musk would analyze the pivotal moments in their games. "I am wired for war," he told Farooq, describing the exact point when he knew victory was inevitable.

Meier himself never could have predicted how his "game about the history of civilization" would influence a generation of players.3 For him, it was always about creating interesting decisions, not encoding a particular worldview or training future tech moguls.

"A game," he would later write, "is a series of meaningful choices." In 1991, he had given the world a new way to play with history, to reimagine it, to learn from it. And for countless players who whispered "just one more turn" as dawn broke outside their windows, he had created something else entirely: a whole new civilization.

Two From Today

My weekly picks for recent AI-related articles worth reading.

First from

’s :Is OpenAI's new story-generating model good at writing?

As someone who uses AI as a co-writer for this newsletter—but deliberately avoids using it for writing fiction and more personal journalism—this piece resonated with me. For me, relying on AI for these more intimate forms of writing would undercut the core reason I write: to articulate and shape the emotions, ideas, and stories that are uniquely mine, through language that emerges from my own lived experience and imagination.

Read’s post is in reaction to OpenAI’s Sam Altman posting a story generated by a new OpenAI model that is good at creative writing. Posting the piece online, Altman said this is the first time he has been “really struck” by AI writing. Read’s post raises important questions about how we read, critique, and understand writing from large language models—not just dismissing or praising the work, but considering how to examine this kind of writing as literature.

Given all the work that goes into cultivating the dramatic experience of an L.L.M. chatbot--and the strong differences users perceive in the personalities and styles of the many different chat apps--why shouldn’t we be treating all text generated by L.L.M.s as a kind of fiction, worthy of close reading?

The idea here isn’t to elevate L.L.M. product so much as normalize it. My strong feeling is that the better we understand what L.L.M.s are, how they work, what they’re good at, their relationship to meaning and language, etc., the closer we get to making them objects of democratic control, rather than as private oracles to which we submit.

Second, from

:The Cat in the Tree: Why AI Content Leaves Us Cold

In a world increasingly filled with sophisticated but soulless AI creations, what genuinely moves us might be surprisingly simple. This insightful essay beautifully explores why human touch remains irreplaceable in art and life.

Sacasas contrasts an AI-generated music video with the simple delight of discovering a small cat painted on a tree during an afternoon walk. While the sophisticated yet forgettable AI creation left the Sacasas cold, the humble painting inspired genuine surprise, warmth, and connection.

The essay explores why human-made art resonates deeply, suggesting it's because of intention, generosity, and the personal touch inherent in creative acts. Ultimately, Sacasas argues that in an era marked by loneliness and artificial perfection, we don't need flawless simulations of human creativity—we need tangible reminders of human presence and care.

Sid Meier and the Meaning of “Civilization”: How one video game tells the story of an industry, The New Yorker, September 22, 2021

Elon Musk by Walter Isaacson (p. 45 Kindle version)

“I’ve been playing Civilization since middle school,” the Facebook C.E.O., Mark Zuckerberg, wrote in a post on his Web site. “It’s my favorite strategy game and one of the reasons I got into engineering.” From Sid Meier and the Meaning of “Civilization”: How one video game tells the story of an industry, The New Yorker, September 22, 2021

I've been looking forward to this one - 1991 is such a weird year because of how many things happened (Soviet Union, India's privatization, The Web) and Civilization as well to boot

Nice piece :)