A quick note before we dive into 1990.

This week, I want to start by sharing something a bit different. While we’ve been exploring AI’s evolution through the decades in this newsletter, I recently published a profile of

for The Philadelphia Citizen, about her recently updated and revised book and ongoing work about our relationships with smartphones. Price’s research reveals how dramatically our behavior changed without conscious reflection when these devices entered our lives. You can read the article here:It’s Not You. It’s Me - Philly-based science journalist Catherine Price reframes our phone habits as a relationship rather than a moral failing, creating space for honest reflection in an otherwise charged conversation

I’ve been drawn to Price’s substack

and her work in general (you may remember me referencing her work after my essay, The Year Was 1982), because of how urgently it applies to our current AI moment. We are in danger of repeating the same patterns — adopting powerful AI tools without carefully considering how they shape our thinking, attention, and creativity. But unlike smartphones, which announce their presence in our hands, AI’s influence may be even more subtle in how it rewires our brains and behaviors. How our decision-making shifts when filtered through algorithmic suggestions? What mental processing we erode when we co-create written passages with AI? These questions feel increasingly important as these tools become more seamlessly integrated into our daily lives.Some of you have asked about my own experience at this intersection, and I’m planning to dive deeper into this process in future essays. I started this project because I enjoy the rich irony of using AI to chronicle the history of AI, like having a mirror study it’s own reflection, and I’d like to explore that paradox more explicitly.

On a practical note, I’ve noticed many of you are reading these essays on email, but you might not know that the Substack app offers audio versions of each of week’s essay. If you’re someone who may prefer to absorb my weird essays while walking, driving, or just resting your eyes, consider giving the app a try. Yes, the voice reading the essays is AI (not my own), and yes this maybe a clear example of adopting powerful AI tools that I just referenced, by I’ve come to appreciate the nuance of the AI audio voices in the app.

Last, but I’ve been deliberately quiet about growing this newsletter’s subscriber list — treating it more as an experimental space than a growth project. But, I’m really grateful for feedback I’ve received from many of you, and have decided to put more effort into trying to grow this project. So, if you’ve found value in this weird historical journey through AI’s development, I’d be grateful if you’d share it with others who might appreciate this approach. I think this newsletter is attempting something a bit different from most AI newsletters — looking backward to see forward more clearly, and looking at the human context of technological evolution.

So, in the coming weeks, I’ll also be sharing some updates to subscription tiers to better support my efforts and serve this growing community. More on that soon.

As always, thanks for your time and attention.

Now, let’s get back to the 90s.

Winter had come for artificial intelligence. The grand dreams of the 1980s—of expert systems that would encode human knowledge and replace fallible decision-making—had collapsed under their own weight. The funding dried up, the optimism faded, and AI found itself at an impasse. If machines couldn’t reliably reason through complex problems, what was the point?

Yet even as the current AI winter settled in, something else stirring. Not in the form of new funding or major breakthroughs, but in the very way people thought about intelligence—both human and artificial. If the old models were breaking down, it wasn’t just because they had technical flaws. It was because they had the wrong idea of intelligence to begin with.

Ray Kurzweil thought artificial intelligence was inevitable. A prolific inventor, futurist, and AI pioneer, Kurzweil had already made his mark on developing reading machines for the blind, speech recognition software, and advanced music synthesizers. By 1990, he was turning his attention to AI’s future, arguing that intelligent machines weren’t a question of “if” but “when.” In his book from that year, The Age of Intelligent Machines, he envisioned a world where AI would be woven into the fabric of human life, shaping everything from work to warfare, education to entertainment. The book wasn’t just a technical roadmap; it was a cultural document, a manifesto for AI’s future, even as its present floundered.

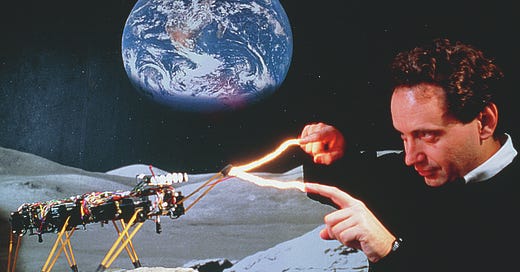

Kurzweil, still operating within the traditional paradigm of machines that would eventually "think" like humans, nonetheless pushed the conversation beyond academic circles. The ideas weren’t confined to print. The book emerged from a short film he made in 1987 as traveling science museum exhibit, bringing AI’s promises—and pitfalls—to the public. Kurzweil’s vision wasn’t of cold, distant logic, but of AI touching everyday life, even featuring his friend Stevie Wonder, an early adopter of his music technology. AI wasn’t dying; it was being reframed.

Meanwhile, Daniel Dennett was issuing a warning. The Turing Test—the most famous benchmark for AI—had become a distraction. Originally conceived as a challenge to define intelligence in practical terms, it had instead become a tool for self-deception. AI could fool people into believing it was intelligent, but was it? In 1990, Dennett called out the mistake of mistaking performance for understanding, a caution that would echo for decades as chatbots and machine-learning models followed the same pattern. His critique highlighted a fundamental problem: AI had been chasing the appearance of intelligence rather than its essence, focusing on what systems could convince humans they were doing rather than what they were actually capable of.

And then there was Rodney Brooks. While Kurzweil was dreaming big and Dennett was urging skepticism, Brooks was tearing the old models down completely. In Elephants Don’t Play Chess, he argued that AI researchers had been going about it all wrong. Intelligence, he said, wasn’t about planning or abstract reasoning—it was about moving, sensing, interacting with the real world. Traditional AI had tried to build intelligence from the top down, coding vast rule sets into machines. Brooks proposed a radical alternative: start from the bottom up, and let intelligence emerge from interaction.

His subsumption architecture, powering MIT’s mobile robots, wasn’t elegant in the way symbolic AI was supposed to be. It didn’t manipulate symbols or follow rigid rules. Instead, it responded to its environment in real-time—learning by doing, not by reasoning. The robot Genghis, a six-legged insect-like creature, embodied this new approach. Without complex internal models or chess-playing algorithms, Genghis could navigate rough terrain, respond to obstacles, and adapt to unexpected situations—all with a fraction of the computing power required by traditional AI systems. It was messy, reactive, and surprisingly effective—an idea that would become the foundation of modern robotics, influencing everything from self-driving cars to reinforcement learning.

And it wasn’t just AI that was having a reckoning in 1990.

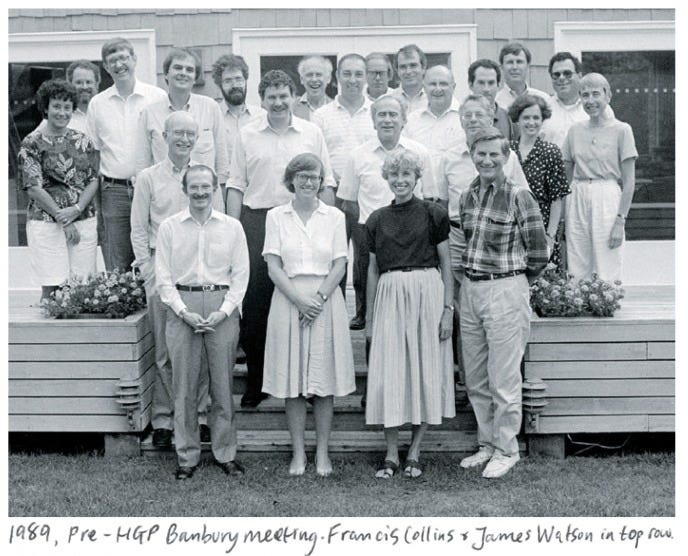

Across the scientific world, another grand project was being questioned. The Human Genome Project promised to map every gene in human DNA, a monumental effort to sequence the "code of life." But its critics weren’t convinced.1 They argued that simply collecting data—however vast—was not the same as understanding it. Mapping every gene wouldn’t tell scientists how they worked, just as AI’s expert systems had compiled vast stores of knowledge without true intelligence.

Both fields were confronting the same realization: knowing "what" wasn’t enough without knowing "how."

As AI researchers were beginning to reject hardcoded reasoning models, biologists were questioning the value of sequencing without interpretation. Critics of the Genome Project worried that they would end up with a massive catalog of human genes but few insights into how those genes actually functioned. AI had millions of symbolic rules, but no adaptability. Genomics had millions of genetic sequences, but no roadmap to meaning. Each field seemed to be sensing that a different approach might be needed—one that would emphasize patterns and relationships over mere cataloging of facts.

Both would need a paradigm shift. AI would eventually turn to machine learning, relying on data-driven models rather than hand-coded rules. Genetics would move toward systems biology, recognizing that mapping genes wasn’t enough—what mattered was how they interacted to create life itself. But in 1990, neither was ready to take that leap.

The year before, the Berlin Wall had fallen, bringing an end to decades of rigid ideological confrontation. 1990 felt like an unraveling of assumptions—not just in global politics, but in AI and biology as well. If intelligence wasn’t about hardcoded logic, and if mapping DNA wasn’t about understanding life, then what were they? The very foundations of these fields were up for debate.

Outside the labs, the world was shifting. The Iraq War was beginning, marking the first major U.S. conflict of the post-Cold War order. Nelson Mandela walked free, signaling the slow death of apartheid. The Hubble Space Telescope launched, offering a new perspective on the universe itself. The old ways of seeing the world—whether through rigid political structures or rigid AI architectures—were being challenged.

AI wasn’t ready to break free from its winter yet, but the cracks were forming. The old paradigms were failing, and the next generation of researchers wasn’t interested in patching them up. Expert systems were crumbling and symbolic walls coming down.The next wave of AI wouldn’t be built on rules, but on adaptation.

The machines weren’t playing chess anymore. They were learning how to move.

Two From Today

First, from

’s here is part one of a seven part series on The State of AI, 2025.In this article, Romero addresses how AI’s evolution is proving to be more paradoxical than ever—progressing rapidly while feeling more uncertain. This piece unpacks the ongoing tension between scale and efficiency, questioning whether AI is settling into its future or still in search of one.

I find that these types of “State of…” articles to vary widely in terms of their value, but I’ve grown to appreciate Romero’s perspective on AI and how he aims to put the human at the center of the story.

Second, I know I’ve been sharing a lot from

lately, but as someone who appreciates Ezra Klein’s perspective on AI, I found this post from Marcus, to be an interesting take on a recent podcast episode that Klein did around A.G.I. and the Government. From :Ezra Klein’s new take on AGI - and why I think it’s probably wrong

Great 15-Year Project to Decipher Genes Stirs Opposition - NY Times article from June 5, 1990 (gift)