The year was 1988, and artificial intelligence stood before its interrogators. "What have you actually accomplished?" DARPA demanded of the field's leaders, their decades of funding suddenly requiring justification. The age of blind faith in thinking machines was over.

In his AAAI presidential address, Raj Reddy faced the question head-on. After thirty years of research, a billion-dollar industry, and thousands of promises, the moment of accountability had arrived. Yet beneath the surface interrogation, something more profound was occurring—the field was learning to question itself.

The LISP machines, once symbols of AI's boundless potential, gathered dust in labs while their makers slid into bankruptcy. Expert systems, those oracles of the early eighties, revealed their brittleness—brilliant within narrow domains but blind beyond their boundaries. Yet paradoxically, they were experiencing their greatest commercial success: a 1988 Gartner study reported that the number of deployed expert systems had skyrocketed from 50 to 1,400 in just one year, with thousands more under development.1 AI, though struggling scientifically, was finding its place in corporate decision-making, finance, and industry.

But in this winter of disillusion, seeds of renewal were quietly taking root. Neural networks, dismissed a decade earlier, found new adherents exploring different paths to machine intelligence. The backpropagation algorithm, largely ignored for years, was finally gaining traction, reviving interest in deep learning. In university labs, researchers stopped promising artificial minds and started building useful tools.

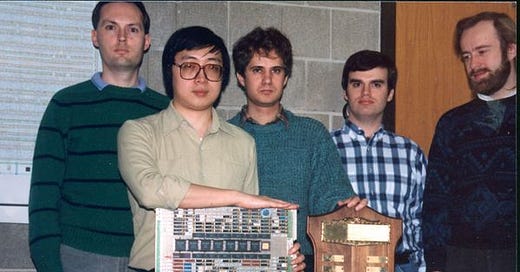

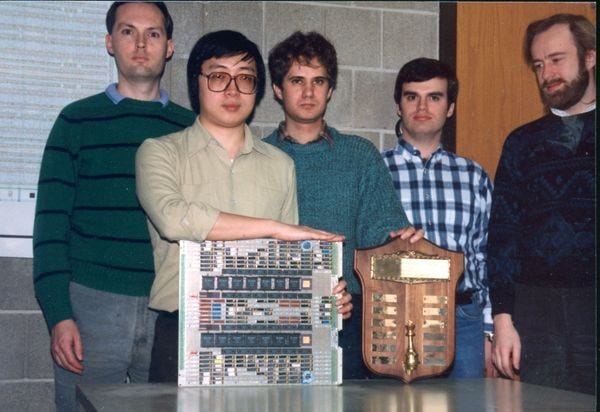

Even as the field tempered its grandest ambitions, quieter victories emerged. CMU's Sphinx system, led by grad student Kai-Fu Lee, achieved remarkable accuracy in speech recognition not by mimicking human hearing but by embracing statistical models and pattern matching.2 Deep Thought's historic chess victory over a grandmaster stemmed not from understanding the game as humans do, but from sheer computational persistence. These successes suggested a new path forward: excellence through specialization rather than the elusive dream of universal intelligence.

The Soviet Union began withdrawing from Afghanistan, leaving ideological certainties as shattered as the landscape. NASA scientist James Hansen testified before Congress on climate change, warning that some patterns, once broken, might never restore themselves.

The first fully digital cellular network launched in Finland, weaving invisible webs of connection that would soon span the world. Growing student unrest in China hinted at deeper tensions that would erupt into mass protests the following year. Stephen Hawking published A Brief History of Time, inviting millions to contemplate the cosmos, just as the Morris Worm, the first major internet virus, exposed the vulnerabilities of our new digital universe.

Meanwhile, Fujifilm introduced the world's first digital consumer camera prototype, the Fujix DS-1P—a quiet but transformative event. It was not just photography that would change, but human behavior itself. Soon, moments would not just be captured; they would be compressed, shared, manipulated, and embedded into the digital fabric of daily life. The analog world was beginning to disappear, pixel by pixel.

The grand visions of artificial minds had not vanished, but they had fractured into something more intricate, more uncertain. Intelligence, once imagined as a monolithic force waiting to be built, was revealing itself as something far stranger and more elusive—a puzzle assembled from imperfect pieces. AI was no longer chasing the dream of synthetic thought but learning, in fits and starts, how to be useful. If the field had once promised gods of logic, it was now content to build tools for mere mortals. Perhaps that was the real breakthrough: not in mastering thought, but in finally understanding its limits.

Three From Today

First, from Kevin Kelly’s The Technium:

Kelly writes about the transition from what he dubs the economy of the Born to the economy of the Made — an economy driven by human growth to one sustained by artificial entities.

The economy of the Born is powered by human attention, human desires, human biases, human labor, human attitudes, human consumption. The economy of the Made, a synthetic economy, is powered by artificial minds, machine attention, synthetic labor, virtual needs, and manufactured desires.

Kelly frames the transition as a response to the declining population rates globally — and the increasing capability of our AI and robotic systems. It isn’t a naive "AI will save us" take, but it is a bold, optimistic vision of an at the same time, unsettling future where humans adapt to declining numbers by coexisting with synthetic minds. It rejects the fear of collapse and embraces transformation, but in doing so, it flirts with a post-humanist perspective, where the economic world is shaped as much by AI as by people.

Second, from

’ :Elon Musk’s terrifying vision for AI

I happen to agree with a lot — not all, but a lot of what Gary Marcus is saying, and warning us about these days. In his post the most chilling point that Marcus makes here in framing Elon Musk’s vision related to recent announcements around the release of Grok 3 is:

“The problem here, by the way, isn’t just the blatant propaganda, but the more subtle stuff, that people may not even notice.

When I spoke to the United States Senate in May 2023, I mentioned preliminary work by Mor Naaman’s lab at Cornell Tech that shows that people’s attitudes and beliefs can subtly be influenced by LLMs.

A 2024 follow up study replicated and extending that, reporting that :

Our results provide robust evidence that biased Al autocomplete suggestions can shift people's attitudes. In addition, we find that users - including those whose attitudes were shifted — were largely unaware of the suggestions' bias and influence [boldface added]. Further, we demonstrate that this result cannot be explained by the mere provision of persuasive information. Finally, we show that the effect is not mitigated by rising awareness of the task or of the Al suggestions' potential bias.”

In short LLMs can influence people’s attitudes; people may not even know they have been influenced; and if you warn them, they can still be affected.

Grok 3 is designed to be a nuclear propaganda weapon, and Musk is proud of it.

Some may call it hyperbole, but I believe we ignore it at our peril.

Finally, from

of viaA Quantum Breakthrough is Coming in AI:

AQ represents a “moonshot” synergistic integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Quantum Computing, highlighting how both technologies can enhance each other. By combining the distinct capabilities of AI and quantum technologies, AQ promises revolutionary advancements across various fields.

From McNulty:

Foundations and Grand Challenges of Artificial Intelligence: AAAI Presidential Address, Raj Reddy, AI Magazine, 1988

Talking to Machines: Progress Is Speeded, The New York Times, 1988 (gift)