The year was 1984, and in a Tampa stadium, 72,920 souls watched the Los Angeles Raiders crush the Washington Redskins 35-9, while another 77 million Americans tuned in to the lop-sided contest from their living rooms.

During the third quarter break, on those millions of television screens across the nation, a nightmarish industrial landscape appeared.

Rows of gray-faced humans, heads shaved, marched in lockstep through blue-tinted corridors. They filed into a massive theater, eyes glazed, while on a towering screen, Big Brother droned about "information purification directives."

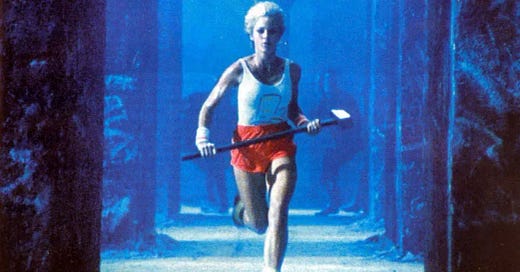

Then: a flash of color. A young woman in orange shorts and a white tank top, pursued by police in riot gear, sprinted down the center aisle. The hammer she carried swung in a perfect arc toward the screen. Just before impact, everything went black.

"On January 24th, Apple Computer will introduce Macintosh. And you'll see why 1984 won't be like '1984.'"

The ad, directed by a young up-and-coming director, cost $900,000 to air — more than the $500,000 spent to film it. But Apple's board of directors had initially hated it so much they'd tried to sell off the Super Bowl slot. Only Steve Jobs' stubborn insistence, and the quiet defiance of agency Chiat/Day in missing the deadline to sell the space, had kept it alive.1

“The original concept was to show the fight for the control of computer technology as a struggle of the few against the many,” said TBWA/Chiat/Day's Lee Clow. Apple wanted the Mac to symbolize the idea of empowerment, with the ad showcasing the Mac as a tool for combating conformity and asserting originality.

The promise was clear: personal computing would save us from Orwell's nightmare. Technology in the hands of individuals would prevent the rise of Big Brother.

As millions watched Apple’s ad during Super Bowl XVIII in Tampa, John McCarthy was warning his fellow AI researchers about a different kind of threat. "The 'Look, ma, no hands!' syndrome," he wrote in AI Magazine that fall, describing how the field had become preoccupied with showcasing novelty over substance. "A paper reports that a computer has been programmed to do what no computer program has previously done, and that constitutes the report. How science has been advanced by this work or how other people are aided in their work may be unapparent."

Twenty-three days after that Super Bowl ad, as the first Macintoshes appeared in stores with their $2,495 price tags, Douglas Lenat was settling into his new office at MCC in Austin, Texas. His project CYC had a grander ambition2 than Apple's personal revolution: to encode all human common sense into a single database.3 While Apple promised to smash Big Brother's screen, Lenat and his corporate backers were building a system that would, in his words, "eventually know most of what is known."

If CYC represented corporate America's bid to centralize knowledge, DARPA's Strategic Computing Initiative showed the Pentagon's parallel ambitions.4 In 1984, as Macintosh promised "the computer for the rest of us," DARPA divided its billion-dollar AI program into twelve separate initiatives. Their vision wasn't personal liberation but military control - autonomous vehicles, battlefield management systems, and a "pilot's associate" that could advise fighter pilots in combat.

The irony was stark. While Apple's Super Bowl ad had shown a woman smashing a screen of centralized authority, DARPA was building a pyramid of technologies with artificial intelligence as its capstone. Their goal wasn't to prevent Orwell's nightmare but to make it operational: machines that could interpret photographs, understand speech, and plan battles. Under Reagan's administration, this military-industrial convergence was seen as essential to counter both Soviet power and Japanese technological ambition.

In Washington, as growing trade deficits raised questions about who would control this new economy, and at what cost, the Reagan administration heralded America's economic shift from manufacturing to information and services. The future, they insisted, belonged to innovation and technology and who could control and manipulate information — exactly the kind of centralized power Apple's Super Bowl ad had warned against. But they failed to mention who would control this new economy, or at what cost.

"Artificial intelligence is in the midst of a deep and irreversible structural change," wrote Peter Hart in that same Fall issue of AI Magazine. The field was moving from pure research to commercial applications, from academic labs to corporate offices. But this transition carried its own dangers. Companies were rushing to build expert systems without fully understanding their limitations. Executives were demanding AI solutions without grasping what the technology could actually do.

In research labs across America, the seeds of a different approach to AI were being planted. While most researchers focused on encoding human knowledge through rules and symbols, a smaller group was beginning to explore systems inspired by networks of neurons. The old guard of symbolic AI — who believed intelligence could be reduced to manipulating symbols and following rules through logic gates — was facing challenges from early connectionists, who were suggesting that true intelligence might emerge from patterns rather than programs.

The debate wasn't merely academic. If the early connectionists were right, projects like CYC and DARPA's expert systems were fundamentally misguided. You couldn't capture intelligence by building ever-larger databases of rules and facts. Instead, intelligence might emerge from simpler units working together — more like the distributed processing of a human brain than the centralized control of Big Brother's screens.

McCarthy, who had coined the term "artificial intelligence" back in 1956, watched these developments with characteristic skepticism. The field he'd helped create was facing fundamental questions about the nature of intelligence itself: Could it be captured in databases of rules and facts? Or might it require something more like the distributed processing of a human brain? This eerily paralleled the broader cultural moment: centralized versus distributed control, institutional power versus emergent behavior, Big Brother versus the masses.

Meanwhile at the University of Leicester in England, new DNA fingerprinting techniques were proving that identity itself was distributed, not centralized — written in patterns across billions of cells rather than stored in any single location.5 The parallel to AI research was striking: just as genetic code revealed the distributed nature of biological identity, neural networks were beginning to suggest intelligence might be an emergent property rather than a centralized process.

But, the tension between centralized and distributed systems wasn't limited to laboratories. In Britain's coal mines, Margaret Thatcher faced down unions in a battle between centralized state power and distributed worker resistance.6

In India, the Bhopal disaster showed how centralized industrial control could lead to catastrophic failure.

Even MTV, launching its first Music Awards that year, symbolized a shift in cultural production—giving visual artists, independent creators, and emerging musicians a platform to reach audiences in ways that broke from traditional, centralized network control.

But perhaps nowhere was this tension more evident than in Reagan's landslide re-election victory. His "Morning in America" campaign celebrated both personal freedom and institutional power, individual opportunity and military might. It was a contradiction that Apple's Super Bowl ad had tried to resolve through technology, but by year's end, the question remained: Could the tools of centralized power truly serve the cause of individual liberation?

As 1984 drew to a close, two visions of artificial intelligence competed for the future. As this philosophical battle was taking shape, the practical applications of AI were multiplying. Expert systems were diagnosing diseases, configuring computers, and planning military operations. Each success seemed to validate the institutional approach to AI development, even as each failure hinted at deeper limitations.

In university labs and corporate research centers, the symbolic AI researchers continued building their expert systems and knowledge bases, convinced that intelligence could be captured in ever-larger collections of rules and facts. Meanwhile, the seeds of a different approach were being planted by researchers exploring systems inspired by networks of neurons.

The future was arriving, but like the young woman with the hammer in Apple's ad, it refused to follow the script.

Two From Today and One From 2014

First, picking up from this week’s theme, I highly recommend

’s 2014 article in Harper’s Magazine:Poison Apples (gift as PDF)

Solnit, (who always makes me think), delves into the cultural, political, and technological implications of Apple’s iconic Super Bowl commercial. She critiques Silicon Valley’s self-styled narrative as liberators of society, exploring how technology has enabled surveillance, centralized power, and cultural shifts that echo Orwellian themes. Whether you agree with her critique or not, Solnit delivers it with wit and depth, and connects the dystopian fears of Orwell’s 1984 to our 2014 tech-driven reality, offering a compelling lens on modern digital culture. [Side-share, but since I’m mentioning Solnit and Orwell multiple times, I also highly recommend her book, Orwell’s Roses.]

Second, it’s hard to find a recent AI related article that doesn’t feel relevant to this week’s essay, but

of shares a practical walkthrough of OpenAI’s Operator:OpenAI’s Operator: The good, the bad, and the ugly

Operator is new agent released by OpenAI, that McFarland describes as such:

“Operator is powered by something called the Computer-Using Agent (CUA) - a new model that combines GPT-4o's visual processing abilities with advanced reasoning capabilities. Think of it as an AI that can actually "see" and understand what's happening on your screen, then make decisions about how to interact with it.”

The majority of the post is focused on more practical usage and reactions by the user community, but at the end McFarland gets to the point that I think is worth honing in on:

The launch of Operator signals something bigger - a shift in how we'll interact with the internet.

We're witnessing the start of Browser Wars 2.0, but this time it's not about rendering engines or JavaScript performance. It's about who controls the AI layer that sits between users and the web. With OpenAI, Anthropic, and Google all launching browser-based agents, the competition is heating up. […]

This means websites will evolve in completely unexpected ways. Why? Because they'll increasingly be accessed by AI agents rather than humans. […]

We're not just watching the greatest AI tools emerge in agents - we're also seeing the beginning of a fundamental shift in how we interact with the internet

Finally, the announcement of The Stargate Project this week feels very relevant to the 1984 DARPA backed Strategic Computing Initiative mentioned in this week’s essay, except for the key difference is that while SCI was government-led with corporate participation, Stargate inverts this — it's corporate-led with government endorsement, reflecting the shift in technological power from state to private actors over the past 40 years.

in does a good job of laying out the details of Stargate, link below.OpenAI is Big Winner of Stargate Project

And last, on that note, I asked Claude to compare SCI to Stargate, here’s what it shared:

Key parallels between SCI (1983) and Stargate (2024):

National Security Framing

SCI: Response to Japan's Fifth Generation project and Soviet threat

Stargate: Positioned as counter to Chinese AI advancement

Public-Private Structure with Tension

SCI: Tension between "push" (broad tech base) vs "pull" (specific applications)

Stargate: Tension between government oversight and private sector control (OpenAI/Softbank)

Ambitious Scale/Timeline Mismatch

SCI: $1B over 10 years, criticized as unrealistic

Stargate: $500B over 4 years, similar skepticism about funding reality

Infrastructure Focus

SCI: Built pyramid model with infrastructure at base leading to AI

Stargate: Massive data center buildout as foundation for AI advancement

Overpromising Risk

SCI: "Ordinary naivete, unwarranted optimism...tendency to exaggerate"

Stargate: Similar concerns about job creation claims and timeline feasibility

Key Difference: While SCI failed partly due to centralized government control, Stargate inverts this with private sector leadership - though this may create its own risks around accountability and public benefit.

40 Years Ago, This Ad Changed the Super Bowl Forever - oral history of the ad - NYT (gift)

A Cautionary Tale on Ambitious Feats of AI: The Strategic Computing Program commentary by Emma Salisbury

Highly recommend David Peace’s novel GB84 for an amazing fictional documentation of the miner’s strike

Loved this one, Dave. You've reached the era where I start to have memories, so I'm loving all the references. The debate around different theories of how minds work in cognitive science made me think of this conversation with Larry Barsalou, one of the leaders in "grounded cognition" and constructivist theories. (He also was my post-doc advisor for a time.) You may have listened already, but I thought you'd enjoy. :) Keep up the great work!

https://youtu.be/gTzfLp44HnM