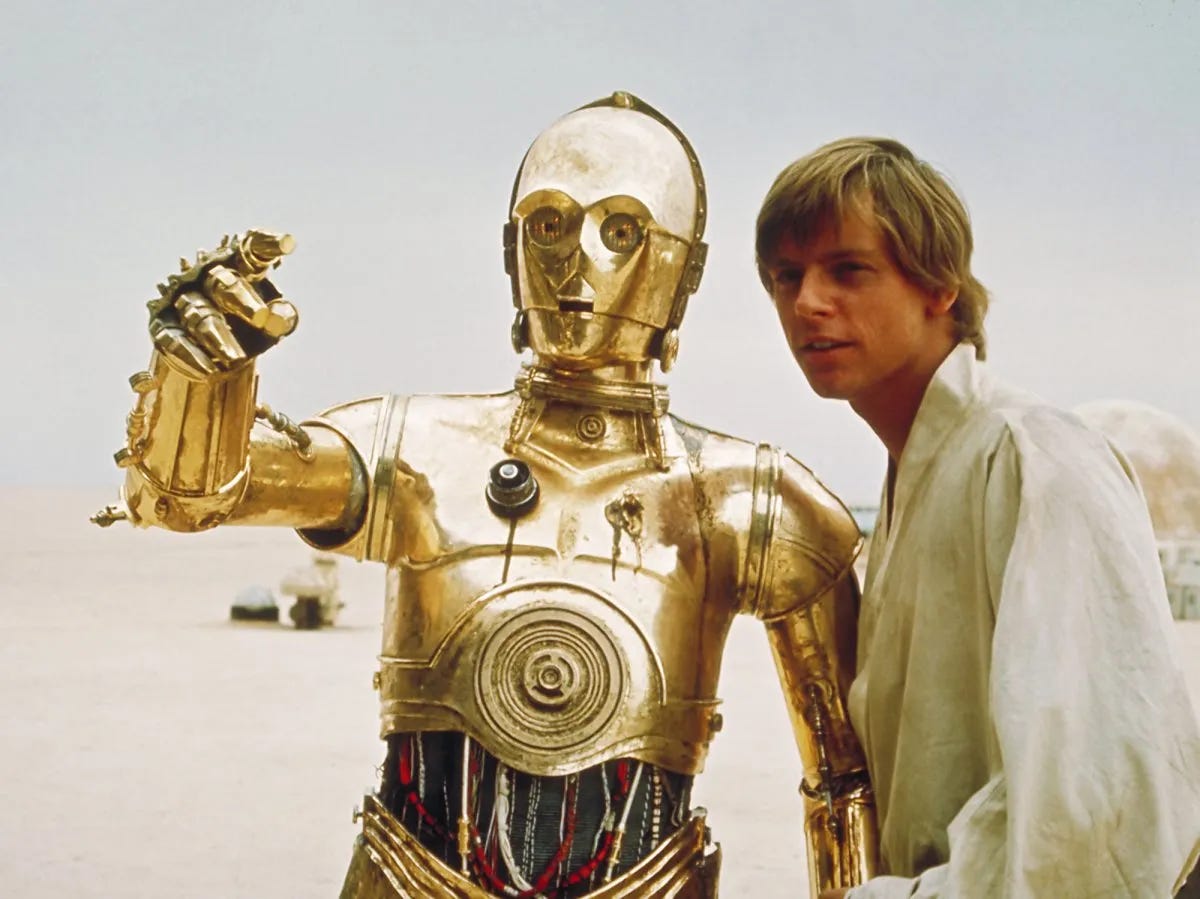

The year was 1977, and robots were learning to bow. Not at Stanford where Shakey the robot had once jerked and stuttered through hallways, or at MIT where Marvin Minsky’s AI Lab still echoed with the dreams of Asimov’s I, Robot — no, these robots were in a galaxy not so far away, at your local cinema actually, where C-3PO was teaching audiences what artificial intelligence could sound like: prissy, proper, and slightly nervous about everything.

"I am C-3PO, human-cyborg relations," he announced, as if good manners were the first thing to be programmed into mechanical minds.

George Lucas, just 33 years old, had created what he called a "space opera," deliberately avoiding heavy science in favor of pure entertainment. While real AI researchers gathered at MIT for the International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, grappling with problems of computer vision, robotics, and natural language processing, Lucas gave the world droids with personalities, fears, and even comic timing. He was, as he told the LA Times that summer, making the movie "Disney would have made when Walt Disney was alive."

In fact, the gap between science fiction and science fact yawned wider than a Sarlacc pit. While C-3PO fretted about etiquette in far-off galaxies, real-world artificial intelligence was still struggling with basic pattern recognition. The field's winter had set in like permafrost, funding frozen by years of unfulfilled promises. Yet somehow, paradoxically, Star Wars was making people believe in AI more than ever - not through demonstrations of actual technology, but through storytelling that bypassed the brain and went straight for the heart.

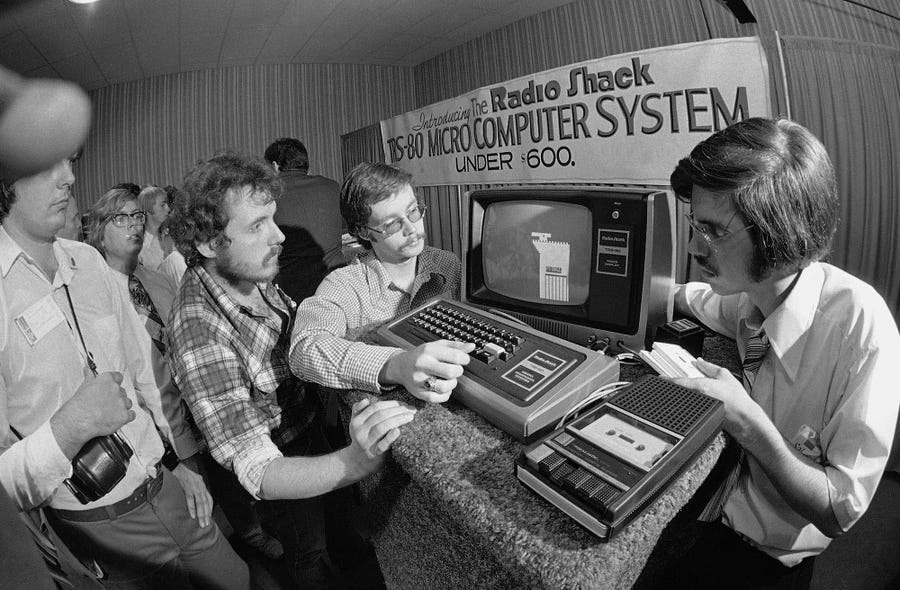

Meanwhile, in the decidedly less glamorous aisles of Radio Shack, the TRS-80 was making its debut. No protocol droids these - just $599.95 worth of beige plastic and possibility, with all the personality of a pocket calculator. But like the droids that captured imaginations in Star Wars, these humble machines were harbingers of a future where computers would become everyday companions.

But, as lightsabers glowed on silver screens, New York City went dark. The summer blackout plunged millions into darkness, while Son of Sam stalked the boroughs.1 Some saw the chaos as proof that civilization was a thin veneer over savagery. Others found community in the darkness, like DJ Kool Herc who was transforming turntables into instruments in the Bronx,2 or those that simply helped strangers navigate powerless streets.

In a way, 1977 was full of such contradictions. As the Sex Pistols screamed "God Save the Queen," Britain's trade deficit screamed for salvation of a different kind. And in the U.S. the KKK was still trying to intimidate, but increasingly finding their rallies broken up by protesters, while in Rhodesia and South Africa, the machinery of apartheid ground on. The world seemed caught between forces of order and chaos, much like the cinematic struggle between Empire and Rebellion.

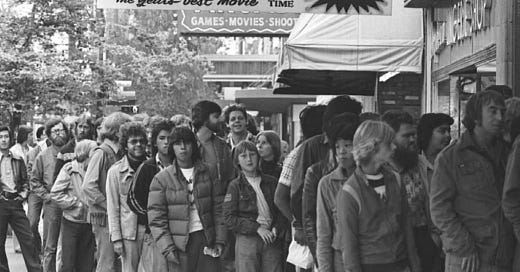

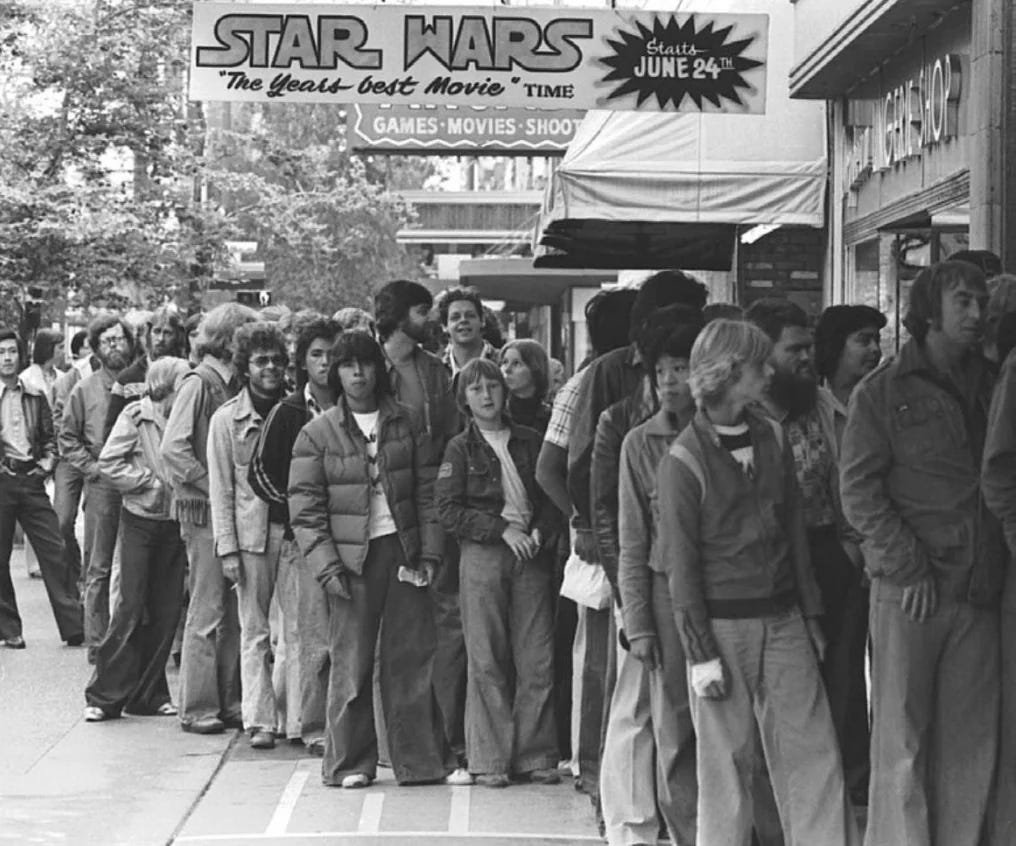

As Star Wars was turning robots into box office gold.3 These examples were all, in their own way, rebellions - against musical convention, against social order, against the cold logic of actual artificial intelligence research. Like the film's clash between mechanical precision and human spirit, the world was balancing on the edge between systematic order and creative chaos.

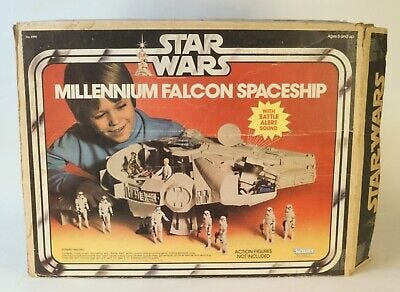

In toy stores across America, Lucas's droids were becoming action figures - literally. "In a way this film was designed around toys," Lucas admitted that summer, lighting up at the subject like a child with a new circuit board. The director who looked "like a brooding scientist" had tapped into something deeper than science: humanity's desire to make machines in its own image, complete with anxieties and attitude problems.

These toys couldn't translate protocol or navigate asteroid fields, but they could make a high school kid feel like Luke Skywalker - a nobody from nowhere about to change everything. By year's end, as Star Wars kept shattering box office records, the distance between our dreams of artificial intelligence and its reality had never been greater. C-3PO and R2-D2 had given us a new way to imagine our relationship with machines: not as masters and servants, but as companions on a grand adventure, complete with bickering, loyalty, and yes, even love.

And perhaps most ironically, as Americans dreamed of droids and hyperspace, real economic power was shifting beneath their feet. China was quietly overtaking the Soviet Union in manufactured exports to the United States, their success at the Canton Trade Fair suggesting a future far different from both Hollywood's space fantasy and Cold War assumptions.4

By the end of 1977, Star Wars had become the highest-grossing film of all time, China had achieved its first trade surplus with America, and the distance between our technological dreams and reality had never been greater - or mattered less. C-3PO might have been fluent in six million forms of communication, but the most important language that year was the one spoken by cash registers, both in movie theaters and toy stores across America, their digital displays clicking upward like coordinates plotting a course to the future.

Two From Today

From MIT News, What do we know about the economics of AI? Nobel laureate Daron Acemoglu has long studied technology-driven growth. This article links out to a number of more in-depth papers that are worth reading, and summarizes how Acemoglu is thinking about AI’s effect on the economy. I asked Claude to summarize the article, and here is what it said:

Acemoglu estimates AI will produce modest economic gains (1.1-1.6% GDP increase over 10 years) rather than the revolutionary changes some predict. Acemoglu argues that current AI development focuses too heavily on replacing workers rather than augmenting their capabilities. He suggests that AI adoption should proceed more gradually and deliberately to minimize potential negative impacts and ensure benefits are widely shared, drawing parallels to lessons from the Industrial Revolution. The article notes that the current hype around AI is driving rapid, potentially misguided investment and development patterns.

From

’s an outlook on what’s to come in 2025

Ladies and Gentleman, the Bronx is Burning by Jonathan Mahler

Lucas: Film-maker with the Force from the LA Times in 1977