The Year Was 1975

And computing power slips through institutional fingers into individual hands

A note.

This week’s essay is heavily based on anecdotes from John Markoff’s book, What the Dormouse Said: How the Sixties Counterculture Shaped the Personal Computer Industry. It’s a terrific read, and I highly recommend all of Markoff’s books for crucial insight into the people and culture who have largely shaped the technology that has come to shape us.

This passage from the preface stands out to me when considering the personal stories and current culture surrounding the tech leaders of today.

“Listen to the stories of those who lived through the sixties and seventies on the Midpeninsula, and you soon realize that it is impossible to explain the dazzling new technologies without understanding the lives and the times of the people who created them. The impact of the region’s heady mix of culture and technology can be seen clearly in the personal stories of many of these pioneers of the computer industry. Indeed, personal decisions frequently had historic consequences.”

The year was 1975, and power was slipping through institutional fingers.

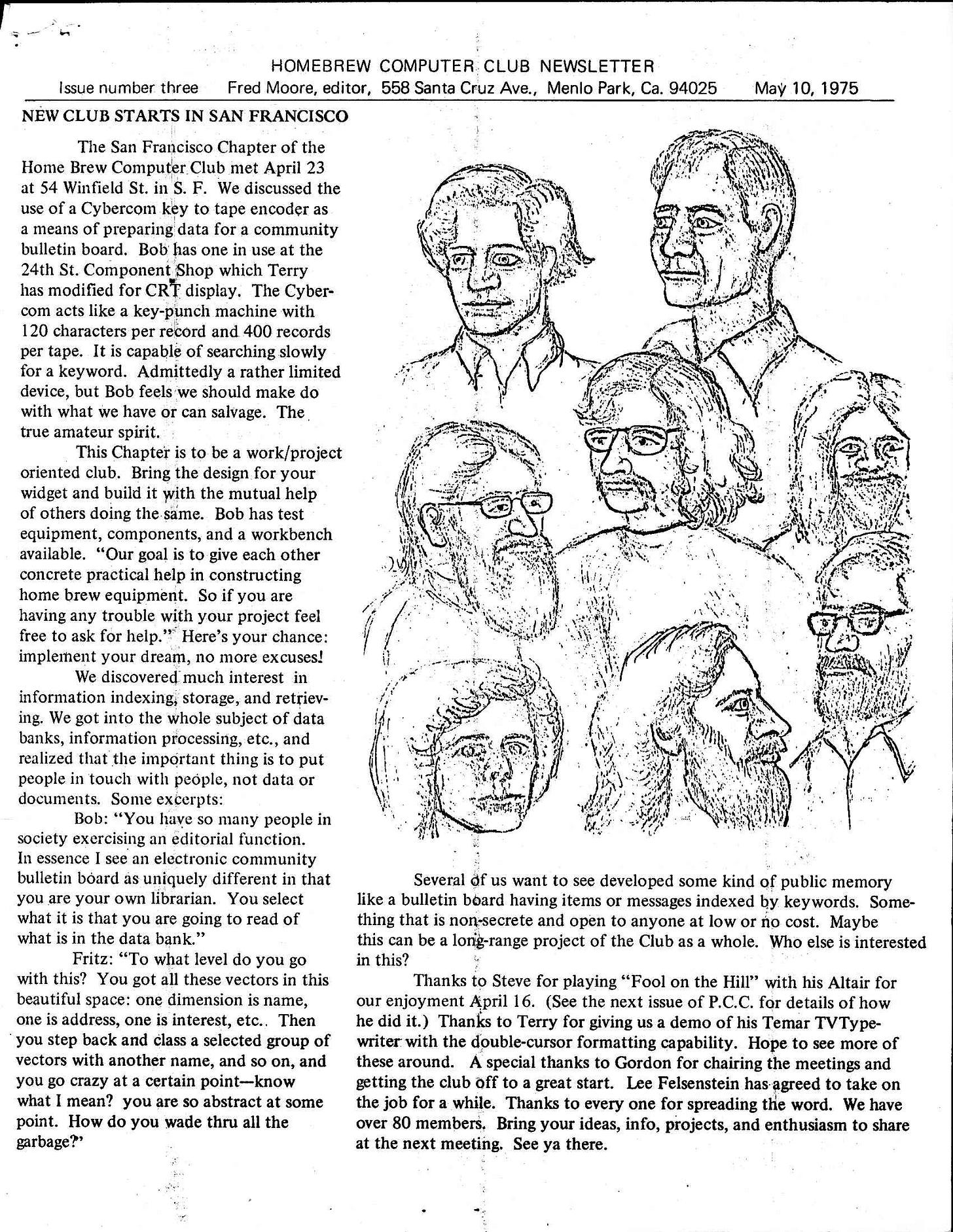

In a Menlo Park garage on a damp March evening, thirty-two people sat wherever they could find space - some on folding chairs, others cross-legged on cold concrete. They were engineers, programmers, hobbyists, dreamers, united by a flyer that had circulated through Silicon Valley: "Are you building your own computer? Terminal? TV typewriter? I/O device? Or some other digital black-magic box?"

The air smelled of wet pavement and possibility. Gordon French's garage, never designed for this many bodies, felt electric with a shared secret: computing power, long locked behind the glass walls of IBM, Xerox, and university labs, was about to escape.

This was the first meeting of the Homebrew Computer Club, though no one present could have guessed they were midwifing a revolution. They couldn't know that from this humble gathering would spring at least twenty-three companies, including one started by a young attendee named Steve Wozniak. They were too busy sharing technical tips, swapping circuit boards, and dreaming of a world where computers belonged not to institutions but to individuals.

Outside in the wider world, established powers were faltering everywhere. Saigon was about to fall, New York City teetered on bankruptcy1, and the first warnings about chlorofluorocarbons eating the ozone layer suggested even humanity's relationship with the atmosphere needed rethinking. But in this garage, a different kind of authority was being challenged - the notion that computing power should remain the exclusive domain of corporations, universities, and governments.

Across the country in his Princeton lab, Paul Werbos was putting the finishing touches on his doctoral thesis - a dense mathematical text that would go largely unnoticed for a decade. His work on "backpropagation" offered machines a way to learn from their mistakes, like a child adjusting their throw after missing a target. But in 1975, as mainframe computers still filled rooms and required priests in white coats to operate them, the idea that machines might learn on their own seemed as distant as personal computers in every home.

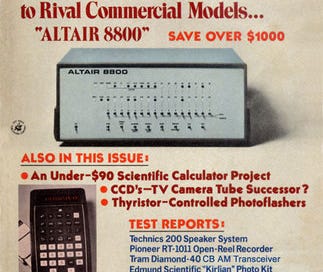

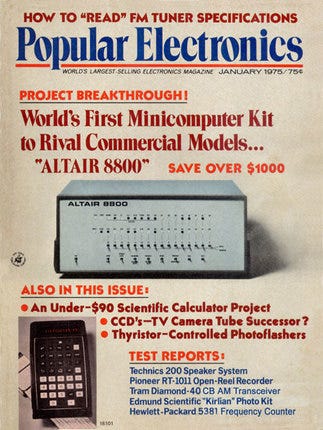

Yet that distance was shrinking faster than anyone in authority realized. In Albuquerque, a company called MITS had begun shipping the Altair 8800, a computer you could own for $397 in kit form. The machine looked more like a dented radio than the sleek mainframes of IBM, and it did practically nothing out of the box. But that was precisely the point - it was a computer you could own, modify, understand. A computer that answered to you, not to an institution.

At one of the early Homebrew meetings, Steve Dompier demonstrated just how personal these machines could become. After laboriously toggling his program into the Altair's front panel switches - no keyboard, no screen - he placed a small AM radio nearby. The room fell silent as the computer's unshielded circuits interfered with the radio in a controlled way, producing an eerily recognizable tune: "The Fool on the Hill." When the last notes faded, the crowd erupted. Here was proof that these machines could create, could entertain, could bring joy.

But not everyone saw joy in this democratization of computing power. In Albuquerque, two young programmers named Bill Gates and Paul Allen had written a BASIC interpreter for the Altair, hoping to sell it to hobbyists. When copies began circulating freely among Homebrew members - shared like peace pipes at each meeting - Gates fired off an angry open letter: "As the majority of hobbyists must be aware, most of you steal your software... Who cares if the people who worked on it get paid?"2

It was more than a complaint about piracy; it was a clash of worldviews. To the Homebrew crowd, software was like scientific knowledge - something to be shared and built upon. To Gates and Allen, it was property, as tangible as the hardware it ran on. This philosophical chasm would only widen in the decades to come, echoing through every debate about open source software, digital rights management, and artificial intelligence.

The same month Fred Moore was circulating his Homebrew flyers by bicycle, military helicopters were evacuating the last Americans from Saigon. One empire was crumbling while another was being born in California garages, though few could see the connection. But both represented a shift in power - from centralized control to distributed networks, from top-down authority to bottom-up innovation.

Inside corporate research labs like Xerox PARC, brilliant scientists were imagining the future of computing. But even their multi-million-dollar Alto workstations couldn't compete with the raw energy of hobbyists armed with soldering irons and a vision of personal liberation through technology. The real revolution wasn't in better technology - it was in who controlled it.

By the time the MITS Mobile rolled into Palo Alto that summer, bringing the Altair on a nationwide promotional tour, the transformation was already accelerating. The demonstration was scheduled at Rickey's Hyatt House, a room booked for eighty people. More than two hundred showed up. They came not just to see the machine, but to touch it, to understand it, to make it their own.

Among the crowd was Lee Felsenstein, who would soon take over as Homebrew's moderator. A former Berkeley activist turned engineer, he carried a long pointer and ran meetings with what he called a "simultaneously autocratic, democratic, and anarchistic style." What emerged under his stewardship was something entirely new: a gift economy of ideas, where the currency was innovation and the interest rate was measured in inspiration.

"Bring back more than you take," became Felsenstein's mantra at each meeting. But what exactly were they taking, and what were they bringing back? The answers to those questions would shape the future of not just computing, but of human knowledge itself.

In this same year, a young engineer named Federico Faggin was perfecting his design of the MOS 6502 microprocessor, which would soon power the first Apple computers. Another engineer at Xerox PARC named Bob Metcalfe was continuing to develop his Ethernet, a way for computers to talk to each other that would help birth the internet. And at Bell Labs, scientists were experimenting with something called Unix, an operating system that treated everything - even other programs - as files to be shared and manipulated.

Each of these innovations carried the same message: the old walls were coming down. Between programs, between machines, between people. The institutional monopoly on computing power was cracking, and through those cracks, a new world was emerging.

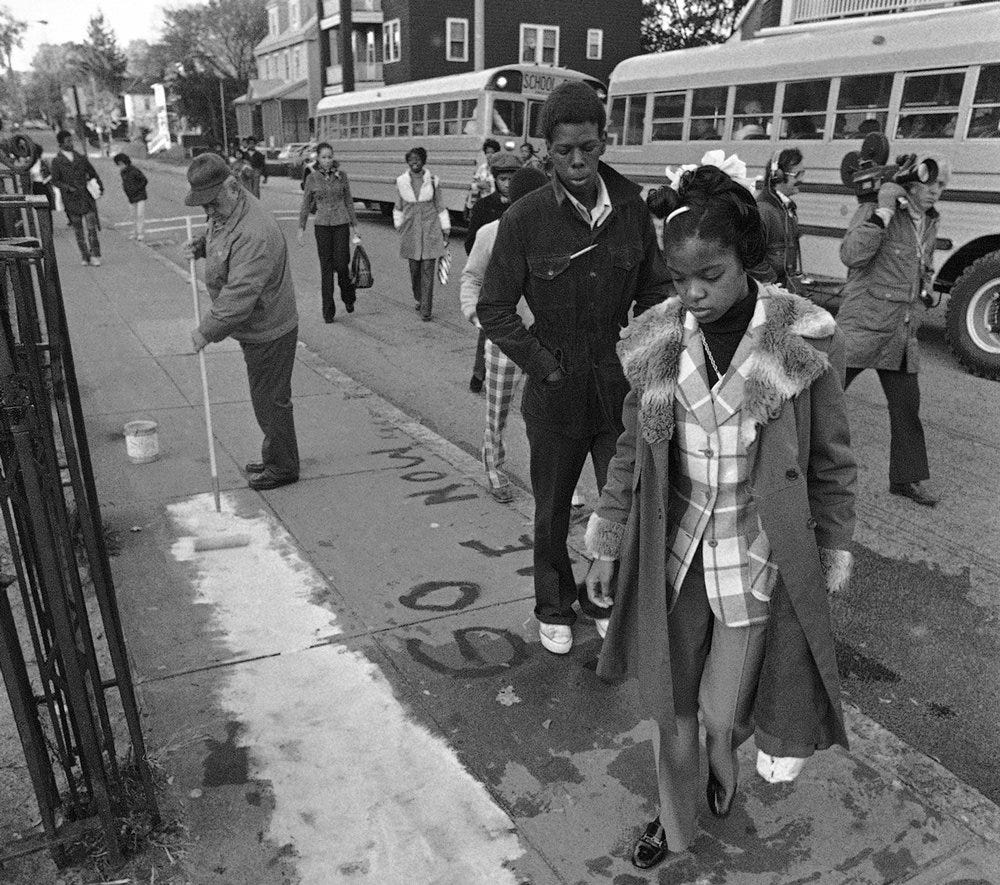

But not all walls fell so easily. As Silicon Valley hobbyists celebrated their liberation from technological gatekeepers, in Boston and Louisville, court-ordered busing to desegregate schools was met with violent protests, bricks thrown through bus windows carrying Black children.

As hobbyists celebrated their liberation from technological gatekeepers in Silicon Valley garages, Black families faced tear gas and police batons for simply trying to enter their children's schools. It was a stark reminder that while some institutional barriers could be breached with soldering irons and clever code, others required a deeper, harder reckoning with America's fundamental inequities.

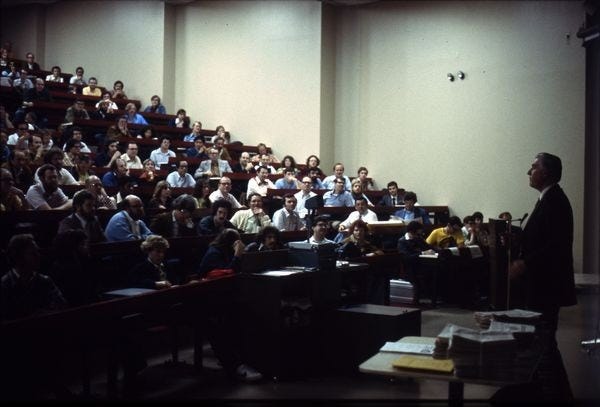

As 1975 drew to a close, Gordon French's garage stood empty. The Homebrew Computer Club had outgrown it, moving first to the Peninsula School, then to the Stanford Linear Accelerator auditorium. Four hundred people would regularly attend these meetings, drawn by something more powerful than mere technology: the idea that computing belonged to everyone.

Fred Moore, who had started it all with his bicycle-delivered flyers, was already drifting away. The club was heading in an entrepreneurial direction he hadn't envisioned, more focused on building companies than building community. He would soon hit the road, hitchhiking east to join anti-nuclear protests, later inventing an efficient wood-burning stove for developing nations. But the seeds he planted would grow in unexpected ways.

The tension he witnessed that year - between Gates's proprietary vision and the hobbyists' sharing culture - would define the digital age. It was the same tension Paul Werbos unknowingly captured in his thesis on backpropagation, describing how machines could learn from their mistakes. Who would control this learning? Who would benefit from it? The institutions or the individuals? Should this technology be locked away in corporate labs and government institutions, or should it belong to everyone? Should it serve profit or community? Can it somehow serve both?

The Homebrew Computer Club would spawn twenty-three companies, including Apple Computer, launching what venture capitalist John Doerr would later call "the largest legal accumulation of wealth in history." But it also launched something else: a way of thinking about technology as a tool for individual empowerment, for community building, for changing the world from the bottom up.

In those garage gatherings of 1975, between the passing of circuit boards and the sharing of code, between Steve Dompier's musical Altair and Bill Gates's angry letter, between institutional control and individual liberation, the future was being negotiated.

The garage is empty now, but the questions that filled it still echo: Who will control these tools? Who will benefit from them? And most importantly, who will they help us become?

Two From Today

From

’s newsletter AI Supremacy, The Chief AI Officer of America, Elon Musk on “How will Elon Musk shape the future of Artificial Intelligence in 2025 and beyond?” (Paywall, but worth it)Lex Fridman’s Interview with Anthropic CEO, Dario Amodei, is bookended by discussions with Amanda Askell is an AI researcher working on Claude's character and personality. Chris Olah is an AI researcher working on mechanistic interpretability.

GREAT JOB, DAVID. I think 1975 was my favorite essay. While this was unfolding before my eyes. I was oblivious to these opposing perspectives.