A Note.

Before we get to 1973, I want to share something about election night — not about who won or lost, but about how we're losing our grip on shared reality.

Last Tuesday night, I went to bed early, but it was already too late.

I don’t typically watch cable news and I’ve never been an active participant in social media. I love PBS Newshour, but otherwise my news diet skews local, which comes from my time as Managing Director of a local nonprofit civic media outlet.) And I have carefully curated my media intake ever since listening to Noam Chomsky speak when I was a student at The New School in 2001.1

(^Short video that gives you some context on Noam Chomsky if you’re unfamiliar.)

And, wow, re-listening to Chomsky now feels like picking up a prophetic radio broadcast from the 1980s, but with the signal remixed by TikTok's algorithm — it’s as if the core message is eerily prescient, but all the key players have been uncannily rearranged. For example, The Manufacturing Consent model he created (see the short video below) still hums with truth, but the gatekeepers have been replaced by algorithms, the flak machines now run on retweets, and we've all become our own media elite.2

My point is that I'm pretty methodical about what news I consume, and how I consume it. I try to read/listen to both sides (nod to Tangle News.) But, I’ve also come to appreciate that understanding media bias doesn't mean surrendering to cynicism. In fact, the loudest voices telling us to distrust all traditional media are often selling their own carefully packaged version of reality.

In fact, the loudest voices telling us to distrust all traditional media are often selling their own carefully packaged version of reality.

Yes, there's wisdom in media skepticism, but there’s also wisdom in recognizing that even flawed institutions (mainstream media) can deliver vital truths. The trick is learning to read the bias without letting it blind you to the facts beneath.

But even with all this careful filtering, my carefully curated media diet couldn’t help but collide with the chaos of real-time political theater on election night. I was struck how each screen and channel was offering its own version of reality, its own narrative of what was happening across America. Each felt simultaneously true and incomplete.

It was too much. I went to bed.

In the aftermath, I couldn't stomach another hot take or think piece on what happened, or what to do next, or worst of all, how I should feel. Instead, my mind kept wandering back to two essays I've read over and over. Two essays written over 15 years apart, that reveal how our collective imagination has been shaped by technology's megaphones — from cable news to social media — and how this affects our ability to process political reality.

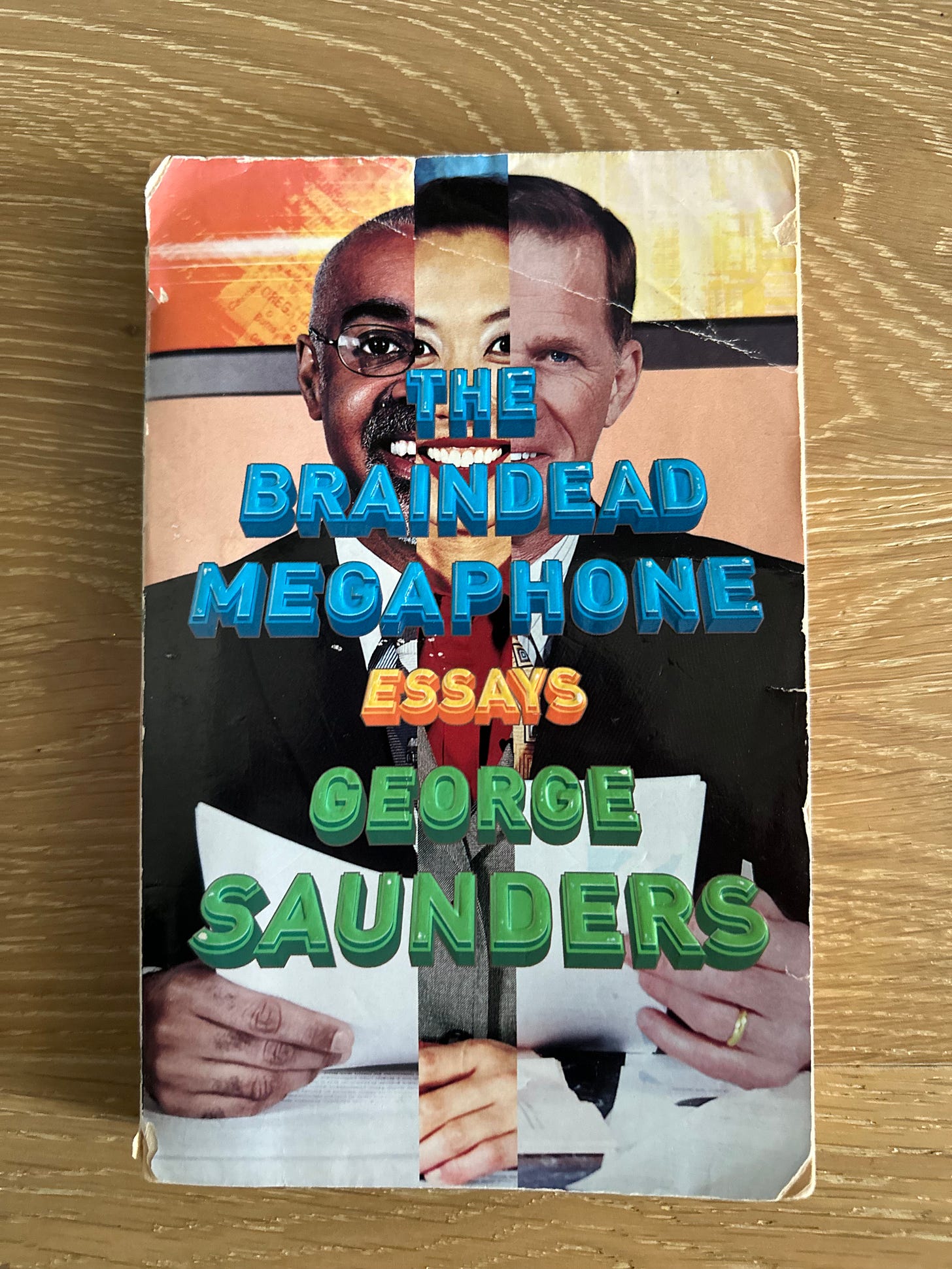

The first essay,

"The Braindead Megaphone,"3 was published in 2007 (in the days of the Iraq War), and on its surface it’s about media criticism — but really, it's about how storytelling shapes our ability to imagine complexly.Saunders sets it up like this: imagine you're at a party where everyone's having these great little conversations. Then some guy shows up with a megaphone. He's not the smartest person there, or the most interesting - but suddenly everyone's talking about whatever he's talking about, just because he's the loudest voice in the room. People begin discussing what he’s discussing, using his phrases, adopting his worldview — not because he's right, but because he's unavoidable.

“His main characteristic is his dominance. He crowds the other voices out. His rhetoric becomes the central rhetoric because of its unavoidability.”

Saunders describes how "the mind mistakes the idea for the world," and in an age of commercial media, these mistakes compound with devastating consequences. His party guest with a megaphone isn't just loud - he's rewriting the stories we tell ourselves about what's possible.

“Mass media’s job is to provide this simulacra of the world, upon which we build our ideas. There’s another name for this simulacra-building: storytelling.

Megaphone Guy is a storyteller, but his stories are not so good. Or rather, his stories are limited. His stories have not had time to gestate — they go out too fast and to too broad an audience.

A culture’s ability to understand the world and itself is critical to its survival. But today we are led into the arena of public debate by seers whose main gift is their ability to compel people to continue to watch them.”

Which brings me to Megan Garber's "We're Already Living in the Metaverse," published in March 2023 in The Atlantic. Garber argues that we've already created the immersive alternative reality that tech companies have been promising — not through VR headsets, but through our phones, screens, and social feeds. As the subtitle describes, “Reality is blurred. Boredom is intolerable. And everything is entertainment.”

“…we will surrender ourselves to our entertainment. We will become so distracted and dazed by our fictions that we’ll lose our sense of what is real.

When we finish one series, the streaming platforms humbly suggest what we might like next. When the algorithm gets it right, we binge, disappearing into a fictional world for hours or even days at a time…

Social media, meanwhile, beckons from the same devices with its own promises of unlimited entertainment. Instagram users peer into the lives of friends and celebrities alike, and post their own touched-up, filtered story for others to consume.

Dwell in this environment long enough, and it becomes difficult to process the facts of the world through anything except entertainment.

Each invitation to be entertained reinforces an impulse: to seek diversion whenever possible, to avoid tedium at all costs, to privilege the dramatized version of events over the actual one. . . it is not shocking but entirely fitting that a game-show host and Twitter personality would become president of the United States.”

Garber traces these developments through the way we’ve become “conditioned to expect that the news will instantaneously become entertainment.” For example, after the school shooting in Uvalde, Texas, Quinta Brunson, the creator of Abbott Elementary shared how she received messages from fans that she write a school-shooting story line into her comedy:

“' ‘People are that deeply removed from demanding more from the politicians they’ve elected and are instead demanding ‘entertainment.’ “

Garber explains how we’ve come to live in multiple realities simultaneously, each with its own rules, language, and version of truth. And she references Hannah Arendt’s studying of societies that were “held in the sway of totalitarian dictators” and how the “ideal subjects of such rule are not the committed believers in the cause. They are instead the people who come to believe in everything and nothing at all: people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction no longer exists.” Simply put:

“A republic requires citizens; entertainment requires only an audience.”

Reading these essays side by side, something clicks into place. Our problem isn't just that we're divided — it's that we're losing our ability to imagine each other as real people. The technology we use every day isn't helping us understand each other better; it's just making the loudest, angriest voices easier to hear.

The challenge isn't just that we're divided, but that our very ability to imagine each other, to think complexly about our shared future, is being shaped by technologies that prioritize volume over understanding, conflict over complexity.

Garber shows us how this technological fragmentation has evolved beyond Saunders' party guest with a megaphone. Now we're all starring in our own personal reality shows, where algorithms feed us exactly what we want to hear and the line between politics and entertainment has completely vanished. Meanwhile, here's the kicker: “We have never been able to share so much of ourselves. And, as study after study has shown, we have never felt more alone.'"

We're not just listening to the wrong stories; we're trapped in multiple, parallel storytelling machines. But there's hope in recognition. As Saunders reminds us:

"every well-thought-out rebuttal to dogma, every scrap of intelligent logic, every absurdist reduction of some bullying stance is the antidote."

And, as the always insightful

highlights in an older essay touching on similar themes, Saunders suggests an “antidote to the sensationalist, manipulative, and altogether reality-warping stories comprising the basic business model of modern media”:“The best stories proceed from a mysterious truth-seeking impulse that narrative has when revised extensively; they are complex and baffling and ambiguous; they tend to make us slower to act, rather than quicker.

They make us more humble, cause us to empathize with people we don’t know, because they help us imagine these people, and when we imagine them — if the storytelling is good enough — we imagine them as being, essentially, like us.

If the story is poor, or has an agenda, if it comes out of a paucity of imagination or is rushed, we imagine those other people as essentially unlike us: unknowable, inscrutable, inconvertible.”

Perhaps that's where we start? Not by shouting louder, but by telling better stories.

I think reading both of these essays in full is worth your time. For me, they've become beacons in the bewildering fog of megaphones and fractured realities. As always, thanks for your time and attention.

And now, onto 1973 . . .

The Year Was 1973

The year was 1973, and winter was coming - not just in the traditional sense, but in the realm of artificial intelligence. The Lighthill Report landed on British desks like the first snow of the season, its cold assessment of AI's practical value sending shivers through research labs across the UK.4 Dreams of machines that could think and talk like humans were dismissed as fantasy, funding froze like puddles used to freeze in December.

Yet even as the frost crept in, places like Stanford managed to protect certain projects, as if wrapping them in a mylar space blanket , and under their warm glow, the MYCIN system trickled through the ice, learning to diagnose bacterial infections with uncanny accuracy,5 suggesting that perhaps machines could be useful without being universal. It was a humble vision of AI - more apprentice than oracle - but it worked.

At Xerox PARC, Bob Metcalfe sketched out something called Ethernet,6 a way for computers to talk to each other across copper cables. In Berkeley, Cohen and Boyer performed a DNA transplant that would transform biology.7 Both were building bridges between previously separate worlds, even as the Yom Kippur War tore others apart.

The science fiction dreams of the '60s were giving way to a more complex reality - one where progress came with prices, and even thinking machines had to learn their limits.

The Supreme Court drew new lines with Roe v. Wade,8 while Watergate erased old ones between right and wrong. Pink Floyd's "Dark Side of the Moon" captured this moment of reckoning, its pulse-like rhythms echoing heartbeats and hospital monitors, its lyrics questioning sanity and systems alike.

As American troops finally withdrew from Vietnam, leaving a landscape as scarred as public trust, another kind of war was unfolding. Arab nations wielded oil like a weapon,9 reminding the West that infinite growth requires infinite resources. Gas lines stretched around blocks, digital displays at stations ticking up prices faster than customers could complain. And as drivers stared at empty tanks, scientists stared at another kind of emptiness: the growing hole in Earth's ozone layer, newly discovered by researchers who wondered what all those aerosol cans were doing to the atmosphere.10

Winter was coming, yes. But humans were questioning if all patterns hold: after winter should come spring, but what if winter doesn’t come at all?

The Indispensable Chomsky (a book that fundamentally changed the way I attempted to understand the world)

In addition to the two short videos, if you want more Chomsky, he created a Masterclass a few years ago: Independent Thinking and Media’s Invisible Powers

I’m not entirely sure if the PDF link to the essay is kosher to share. But, the essay is so great, I couldn’t help myself. Please consider purchasing the entire book if you’re interested. It’s 100% worth it. (Also, Spotify premium gives you access to the audio version of the book, with George reading the essay himself.)

This is beautiful, David. Really enjoyed your perspective on these essays and the string holding them together

“The trick is learning to read the bias without letting it blind you to the facts beneath.” Indeed!