. . . As was the distance between this week’s and next week’s essay. Expect to see The Year Was 1972 on Sunday.

We have 53 essays left to go before we mark the 75th anniversary of Turing’s 1950 paper, Computing Machinery and Intelligence in November 2025. But don’t worry if you are a new subscriber, the weekly essays are meant to stand-alone. Thanks for joining, and as always, thanks for your time and attention — I know it’s precious.

The year was 1971, and the distance between institutions and individuals was about to collapse.

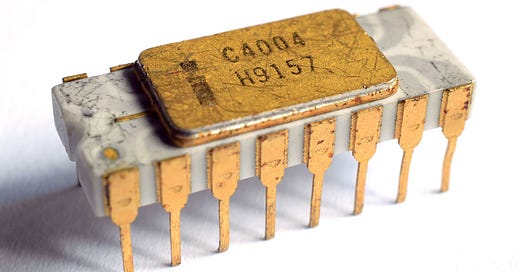

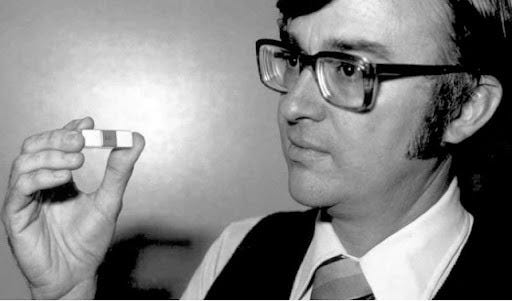

In a suburban office park in Santa Clara, California, Federico Faggin squinted through a microscope at a silicon chip smaller than his fingernail. The Italian-born engineer had packed 2,300 transistors into this tiny space, creating a computer that could fit in the palm of your hand. The Intel 4004, the world's first commercial microprocessor, represented more than just miniaturization – it was a declaration of independence from the mainframe priesthood that had controlled computing power since ENIAC filled a room at Penn two decades earlier.

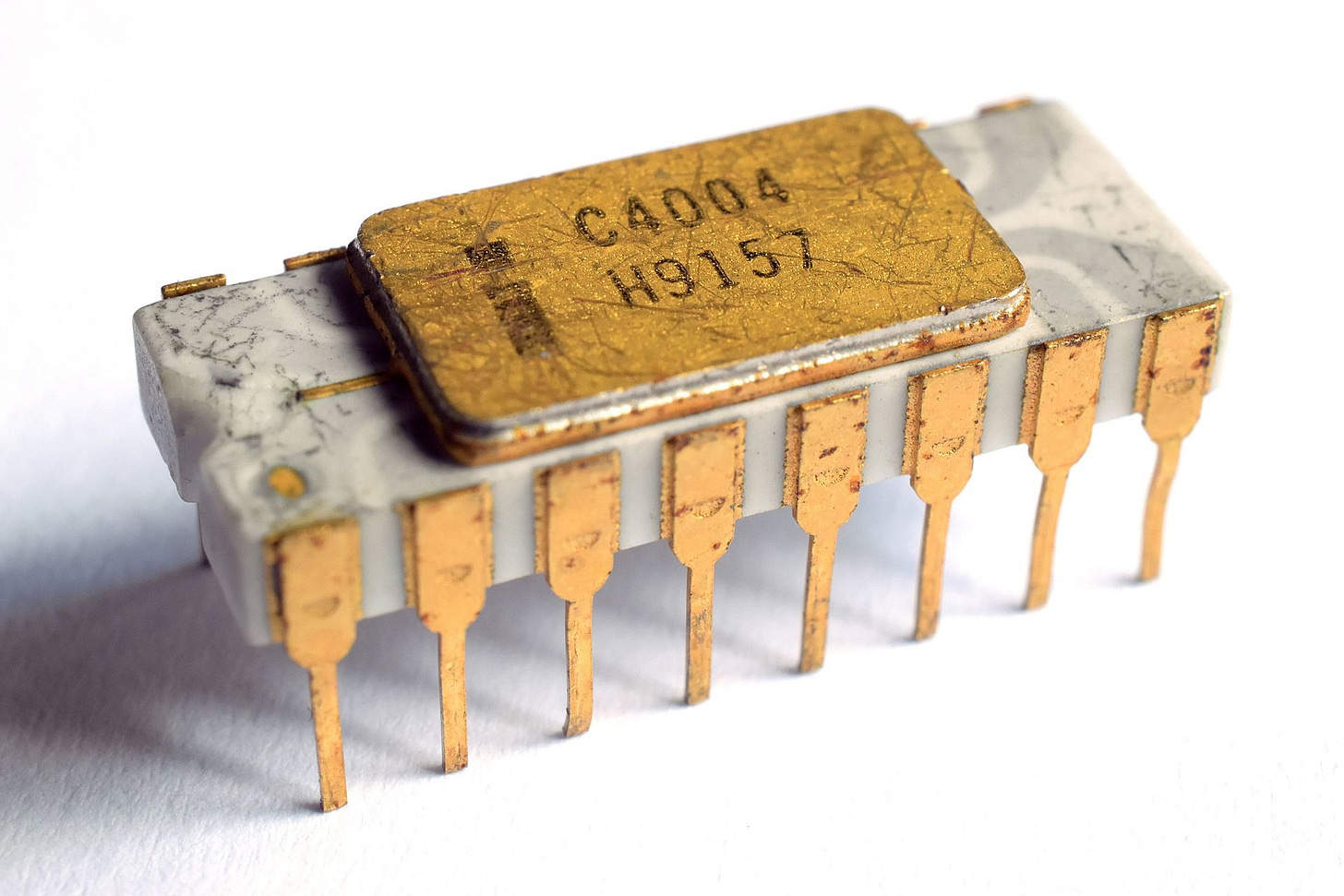

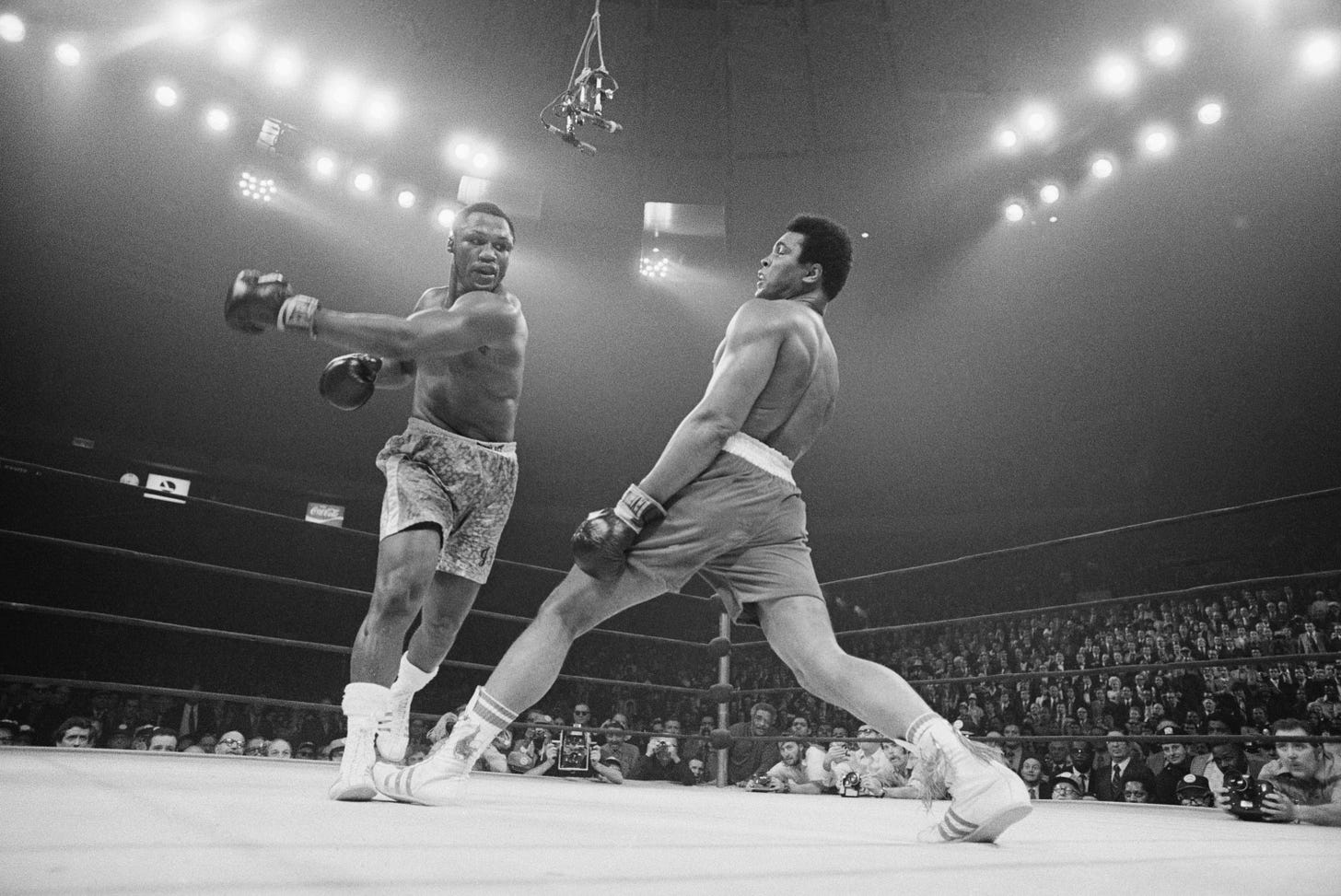

Meanwhile, on the other side of the country, eight anti-war activists were planning their own declaration of independence from institutional power. On the night of March 8th, while Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier commanded the world's attention in their "Fight of the Century"1 at Madison Square Garden, the activists broke into a small FBI office in Media, Pennsylvania.2 As millions watched two men battle in a ring, this band of professors and parents, armed with nothing more than lockpicks and righteous anger, were about to land their own blow against what they saw as a corrupt system.

The story of the Intel 4004's creation was itself a battle against institutional thinking.3 Ted Hoff, Intel's employee number twelve, had spent years fighting the notion that computers belonged only in the hands of specialists. At Stanford, he'd clashed with computer center officials who insisted all computing should be centralized, run by priests of the punch card who controlled access to these electronic oracles. When Japanese calculator manufacturer Busicom came to Intel wanting twelve complex chips, Hoff proposed something radical: a single, programmable chip that could handle multiple functions. It was like suggesting a Swiss Army knife to people who had only known dedicated tools.

The Busicom engineers were skeptical - much like the computer center officials at Stanford had been about individual access to computing power. But Hoff, the kooky inventor who had once balanced broomsticks with toy trains, knew that the future belonged to flexibility and individual control. Under Faggin's meticulous design work, the 4004 emerged: 2,300 transistors crammed onto a single chip, a computer small enough to hold in your palm yet powerful enough to replace a room full of dedicated machinery.

Even after Faggin transformed Hoff's vision into silicon reality, they faced resistance from Intel's own marketing department. "We have diode salesmen out there struggling like crazy to sell memories, and you want them to sell computers? You're crazy," the marketers scoffed, predicting sales of mere 2,000 chips per year.

Back in Media, Pennsylvania, the activists who called themselves the Citizens' Commission to Investigate the FBI had chosen the night of the Ali-Frazier fight carefully. "The night of the fight, the whole town would be listening to the fight," one of them would later recall. "Even the FBI agents would be listening to the fight." While J. Edgar Hoover's agents were likely glued to their radios, the group pried open the office door with a crowbar, their hearts seeming to pound in time with the blows being exchanged at Madison Square Garden. Inside, they found more than they bargained for: documents revealing COINTELPRO, the FBI's massive counter-intelligence program against civil rights and anti-war activists. The bureau that had positioned itself as America's supreme guardian was exposed as a domestic spy agency, monitoring and disrupting the lives of ordinary citizens.4

Just weeks later, in a quiet lab in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Ray Tomlinson was about to strike another blow against centralized control. The bearded programmer at Bolt, Beranek and Newman had been tinkering with a way for researchers to leave messages for each other on shared computers. His breakthrough came in the form of an overlooked symbol on his Model 33 Teletype: @.5 This humble typographical mark would become the bridge between individual and machine, creating a new kind of personal address in an electronic world. The first email was sent between two computers sitting side by side, carrying a message now lost to history - but its importance lay not in its content but in its circumvention of traditional communication channels.

That same summer, on July 4th, a young college student named Michael Hart sat at a computer at the University of Illinois, inspired by a free printed copy of the Declaration of Independence he'd been given at a grocery store. In a moment of revelation, he typed the entire text into the university's mainframe and attempted to send it to everyone on the early computer network. This act of digital liberation would grow into Project Gutenberg, the first effort to make literature freely available to anyone with a computer. Like the microprocessor and email, it represented another crack in the wall of institutional control - this time, challenging the traditional gatekeepers of knowledge and literature.6

And later that summer, The New York Times began publishing the Pentagon Papers, exposing how multiple administrations had systematically lied about Vietnam. Daniel Ellsberg, like the Media activists and Intel's renegade engineers, had decided that institutional power needed to be challenged. The documents revealed not just deception about the war, but the arrogance of institutional thinking - the belief that the public couldn't handle the truth, that information must be controlled from above.7

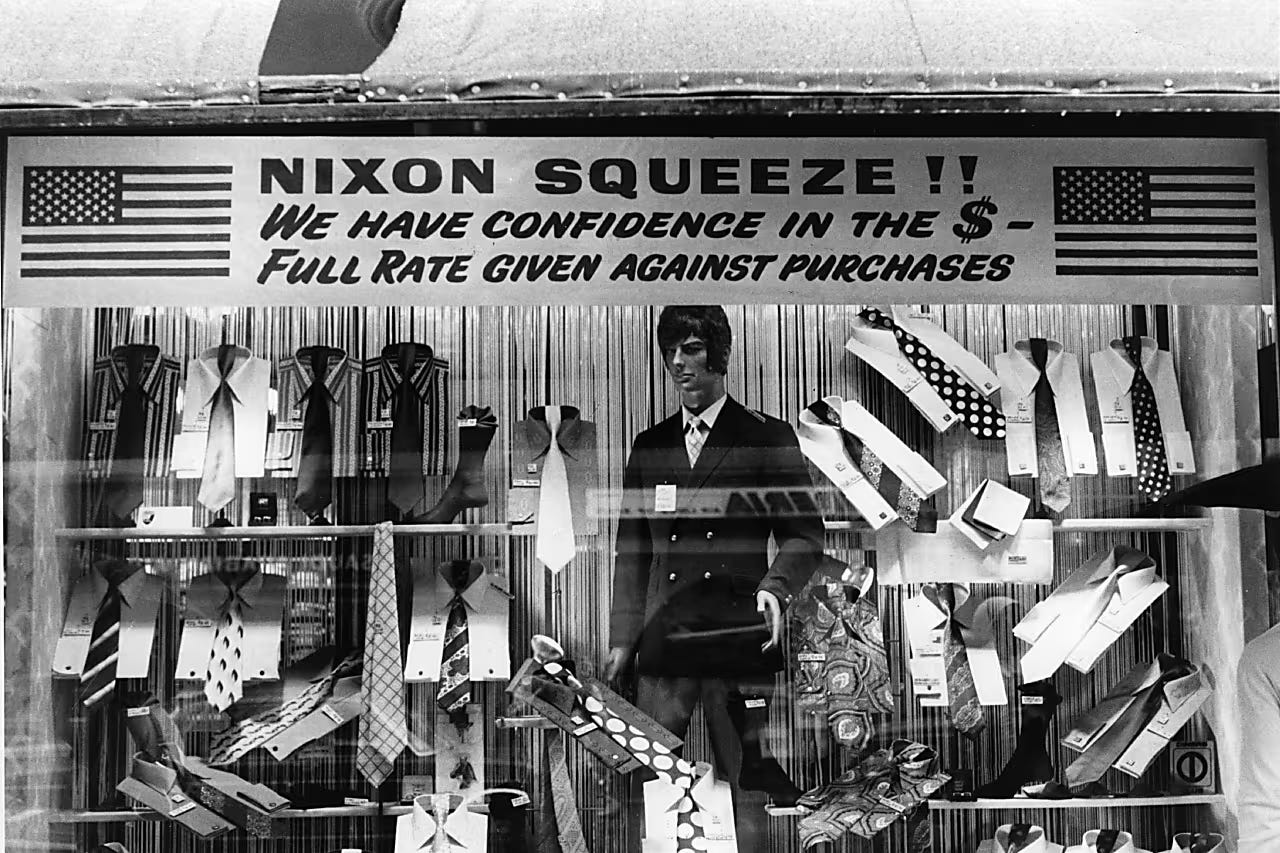

While the nascent NASDAQ stock market promised to democratize financial trading. NPR began broadcasting, giving voice to local public radio stations across the country, and the economy was shifting from institutional to personal control - when Nixon announced wage and price controls, it marked the last gasp of top-down economic management.8

The Bangladesh Liberation War erupted, showing how even nation-states - those supreme institutions of the modern era - could be challenged from below. When China took Taiwan's seat at the United Nations, it marked another shift in the global order. The world was becoming too complex for simple institutional control.

Even the space race, once the domain of competing superpower institutions, was changing character. As the Soviet Union launched Salyut 1, the first space station, visionaries like Gerard K. O'Neill were already imagining space colonies built not for national glory but for individual human settlement. The final frontier, it seemed, might belong not to nations but to people.

In a seedy hotel room in Las Vegas, Hunter S. Thompson was putting the finishing touches on Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas - A Savage Journey to the Heart of the American Dream a book that would shatter institutional journalism's pretense of objectivity. Thompson's gonzo style suggested that personal, subjective truth might be more honest than institutional attempts at detachment. The same message was echoing through science with the adoption of CT scans — sometimes you needed to look at things from multiple angles to see the whole truth.9

By year's end, that tiny Intel chip had begun its quiet revolution. Like the @ symbol in email addresses, like the leaked Pentagon Papers, like the exposed FBI files, it represented a fundamental shift in power. The institutions that had dominated the post-war era - government bureaus, corporate hierarchies, media conglomerates - were facing a future where individuals could process information, communicate, and organize in ways previously unimaginable.

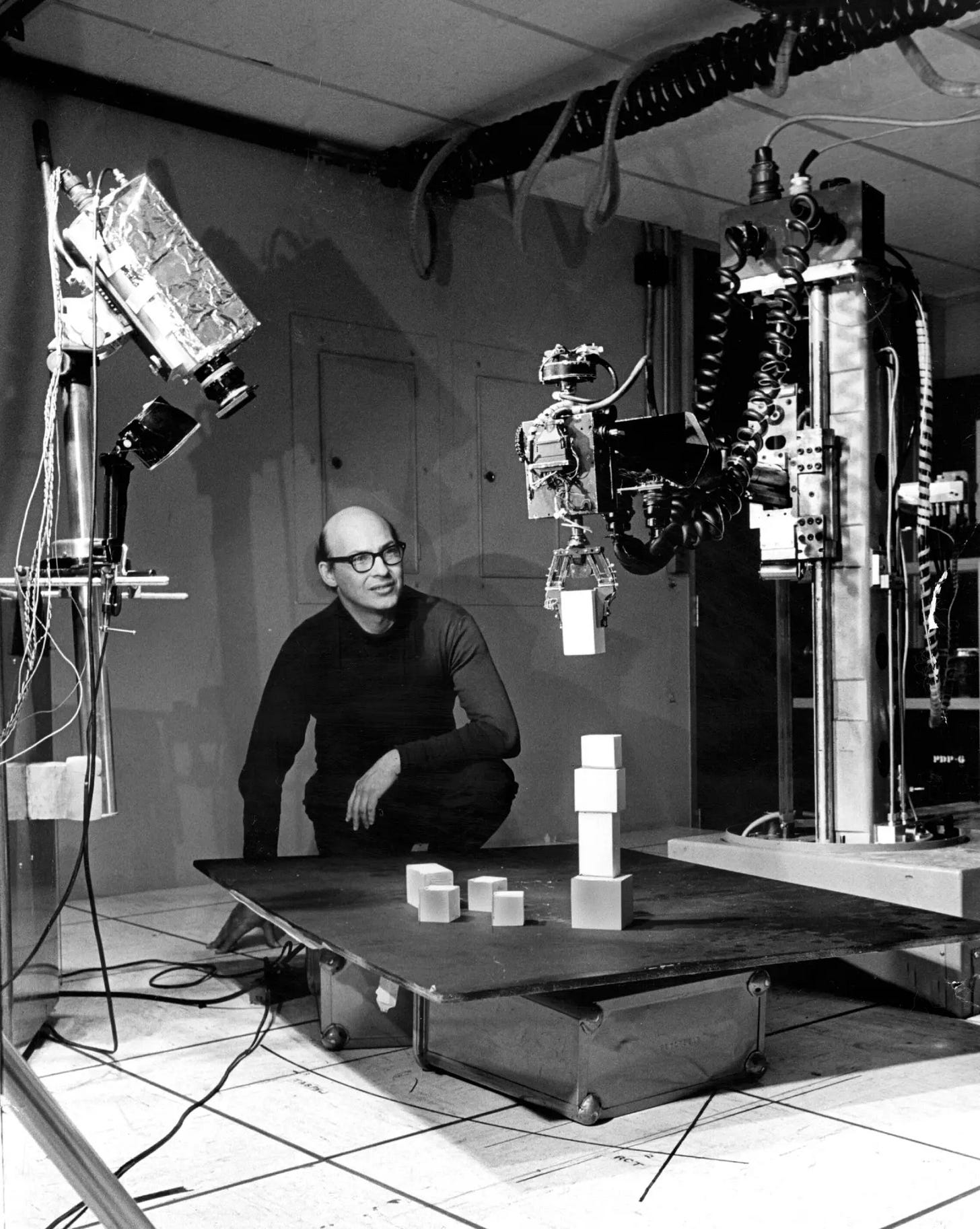

Even within the temples of artificial intelligence, institutional walls were cracking. At MIT, Marvin Minsky's recent split from Project MAC to form the separate AI Lab had created a new kind of research environment, where talented programmers like Richard Stallman flourished in a more independent atmosphere. Yet AI development itself remained tethered to massive mainframes and specialized laboratories, waiting for the personal computing revolution to catch up with its ambitions.

And finally, an economist named Herbert Simon quietly coined a phrase that would prove prophetic: "the attention economy." In a world of abundant information, he argued, the scarce resource would be human attention.10 As personal computers and electronic messages proliferated, as alternative voices like NPR began broadcasting, as the NASDAQ created new ways for individuals to access financial markets, Simon's insight suggested a future where institutional power would have to compete for attention rather than simply command it.

Back in Santa Clara, as Federico Faggin made final adjustments to the 4004's design, he couldn't have known that he was helping to forge the tools that would make Simon's prediction reality. Each of those 2,300 transistors was more than just a switch - it was a tiny declaration of independence, a microscopic warrior in the battle between institutional control and personal empowerment. The distance between the two hadn't just collapsed; it had been bridged by silicon and imagination, by courage and conviction, by the relentless human drive to make the abstract personal and the institutional individual.

Two From Today-ish

Inside the AI Factory was an article published last year by the great, Josh Dzieza in The Verge. I don’t know how much has changed, but this article has stuck with me since I first read it. For example: “Much of the public response to language models like OpenAI’s ChatGPT has focused on all the jobs they appear poised to automate. But behind even the most impressive AI system are people — huge numbers of people labeling data to train it and clarifying data when it gets confused. Only the companies that can afford to buy this data can compete, and those that get it are highly motivated to keep it secret. The result is that, with few exceptions, little is known about the information shaping these systems’ behavior, and even less is known about the people doing the shaping.” Dzieza’s article introduces us to a few of those people.

I Was Made of Language written in Nautilus by Julie Sedivy is a beautiful meditation on “how language shapes time and linguistics uncovers deeper understanding.” “The more I studied it, the more lessons it offered about what it is to live a human life. Language was proving to be an archaeological site of the human condition. By patiently sifting through its layers, one could discover not just our urge to enter other minds, or the inevitable gulfs that remain between us, but also what it means to live within the substance of time.” The article is an excerpt from Sedivy’s book, Linguaphile - A Life of Language Love, which seems to touch on many of the hard to penetrate ideas behind the large language models (LLMs) powering recent AI breakthroughs.