Two quick notes before we get to 1968.

First, at the end of this week’s essay I will include links to a few current articles and/or conversations that I found interesting. From the start of this newsletter, I have said that I want to avoid jumping on the hamster wheel of current AI news, but I do read a lot of it, and often find it striking how much it relates to the historical moment I’m writing about. So, going forward I will share a link or two at the end of each essay.

Personally, I still find that I am able to think (slightly) more clearly about the big questions surrounding AI and our adoption of it, by trying to better understand the people and circumstances that created these systems. Human context and historical perspective feel more important than ever before, as our methods of information retrieval (and generation) become more and more dominated by AI and machine learning algorithms.

Second, I am in the process of building out an off-shoot of this newsletter. Essays written solely from my point-of-view without the help of our AI friends, and a bit less esoteric and experimental in style than these essays. (Although, esoteric is typically how I lean, so I can’t promise anything. ;) Look out for a survey asking for feedback in the coming weeks to help me narrow down the topic.

As always, thanks for reading. Now, to 1968 . . .

The auditorium lights dim in San Francisco's Brooks Hall. A hush falls over the crowd of computer scientists, engineers, and curious onlookers. It's December 9, 1968, and the air crackles with an electric mixture of skepticism and anticipation.

On stage, a mild-mannered man in a white shirt and dark tie settles into a custom-designed console chair. This is Douglas Engelbart, a 43-year-old engineer from the Stanford Research Institute. To many of those in attendance, he's an obscure figure. But in the next 90 minutes, he's about to blow their minds.1

Engelbart clears his throat and begins: "If in your office, you as an intellectual worker were supplied with a computer display, backed up by a computer that was alive for you all day, and was instantly responsive to every action you had - how much value could you derive from that?"

The question hangs in the air, pregnant with possibility. This is no mere product demonstration. It's a glimpse into a future where humans and machines work in symbiosis, where technology amplifies our intellect rather than replaces it.

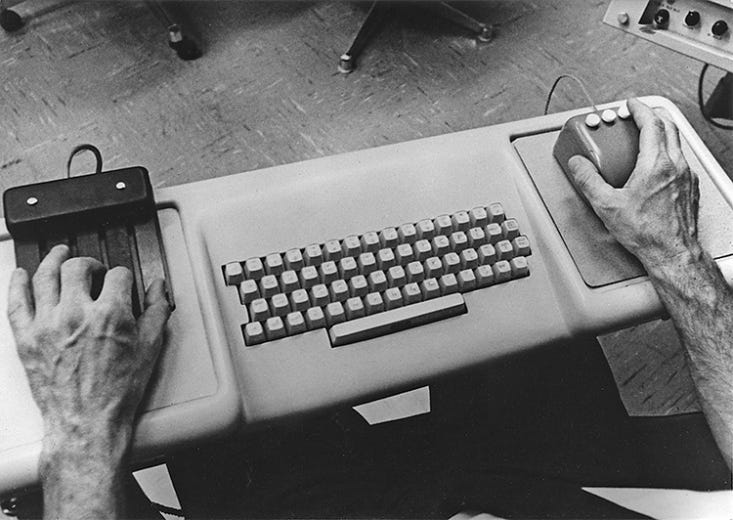

Engelbart's fingers dance across a peculiar keyboard, his left hand manipulating a small box with three buttons - the "mouse"2 - while his right works a five-key chord set. On the large screen above him, text and graphics respond instantly to his commands.

The demonstration is the culmination of years of work, funded by grants from ARPA, NASA, and the US Air Force. Engelbart and his team at the Augmentation Research Center (ARC) at SRI have been developing the oNLine System (NLS) since 1963, driven by a vision of "man-computer symbiosis" shared by J.C.R. Licklider at ARPA. The NLS is a leap beyond the batch processing and punch cards of contemporary computing. It offers real-time manipulation of on-screen data, a graphical user interface with overlapping "windows," and collaborative features allowing multiple users to work on the same document simultaneously.

Months of preparation have gone into this 90-minute plenary session. A complex system of cameras, microwave links, and a custom modem allows Engelbart to control the NLS in Menlo Park from his console on stage in San Francisco. It's a high-stakes gamble - if the demo fails, future funding could be jeopardized. But Engelbart believes that seeing the NLS in action is the only way for people to truly understand its potential.

"I'm doing this with a workstation that's 30 miles away," Engelbart explains, his voice calm despite the groundbreaking nature of what he's showing. The audience leans forward, captivated. In an era when most computer interactions involve punch cards and printouts, this real-time manipulation of digital information seems like science fiction come to life.

As Engelbart demonstrates hypertext links, jumping from one document to another with a simple click, oceans away the tangled web of global politics weaves tighter together.

Just months ago, the world watched as Soviet tanks rolled into Prague, crushing the brief flowering of freedom known as the Prague Spring.3 How might a world of interconnected information change the balance of power between citizens and states?

The demo continues. Engelbart shows off video conferencing, collaborating in real-time with colleagues back at SRI. It's a stark contrast to the breakdown in communication that led to the Tet Offensive in Vietnam, a brutal wake-up call that shattered America's illusions about the war.4

As Engelbart manipulates complex graphics on screen, creating and modifying diagrams with ease, news ticker images flash across TV screens in living rooms: students in Mexico City facing down government troops,5 the chaos of the Democratic National Convention in Chicago.6 In a world increasingly divided, Engelbart’s hoping to reveal tools that could bring people together, allowing them to collaborate across vast distances.

"Let's return to our shopping list," Engelbart says, pulling up a simple text document. With a few keystrokes and mouse clicks, he reorganizes the list, adds items, deletes others. It's a mundane task made extraordinary by the fluidity with which it's accomplished.

Engelbart moves on to demonstrate the system's ability to handle different views of the same information - outlining, full text, filtered views. It's a level of flexibility that seems almost cognitive, as if the machine is adapting to the user's thought processes. Engelbart continues, showing off a vector graphics program, manipulating shapes on the screen with his mouse. The fluid movements of the cursor echo the psychedelic patterns that have become the visual language of the counterculture. Indeed, there's something almost trippy about this glimpse into a digital future, as mind-expanding in its way as the consciousness-altering substances fueling the Summer of Love.

As Engelbart's demonstration concludes, the applause dies down, and a thoughtful silence settles over the audience. In this moment of quiet, the weight of what was just witnessed is difficult to process. Engelbart has shown a vision of the future where humans and computers work in harmony, each augmenting the other's capabilities. But across campus at Stanford, another vision is taking shape.

John McCarthy, the man who coined the term "artificial intelligence," is working towards a different goal: creating machines that can think and reason like humans. The contrast between these two approaches couldn't be starker. On one side, we have Engelbart's vision of Intelligence Augmentation (IA), where technology extends and enhances human capabilities. On the other, we have McCarthy's pursuit of Artificial Intelligence (AI), where machines might one day replicate or even surpass human intelligence.

This divide is more than just a difference in technical approach. It represents a fundamental split in how we view the relationship between humans and machines. Engelbart's demo shows us a world where humans remain at the center, with technology serving as an extension of our minds. McCarthy's work, in contrast, hints at a future where machines might operate independently, potentially rendering human input unnecessary.7

As Engelbart's demonstration draws to a close, a lanky figure in the audience leans forward, his eyes alight with possibility. This is Stewart Brand, photographer, writer, and visionary. Just months ago, Brand launched the first edition of the Whole Earth Catalog, a compendium of tools and ideas for the back-to-the-land movement.8 Now, watching Engelbart's oNLine System in action, Brand sees the digital future of his analog dream.

The Whole Earth Catalog's ethos - "We are as gods and might as well get used to it" - seems to echo in Engelbart's demonstration. Both envision a world where individuals are empowered to shape their environment, conduct their own education, and collaborate in new ways. But while the Catalog focuses on physical tools and communal living, Engelbart is showing us the tools of the mind, the digital implements that could reshape our very way of thinking and working together.

In this moment, two visions of the future converge - the earthy utopianism of the counterculture and the digital utopianism of Silicon Valley's pioneers. It's a powerful collision of ideas. Brand's Catalog, with its emphasis on "access to tools," has already become a bible for the commune movement. But here, in Engelbart's demo, Brand sees a new kind of tool - one that could extend not just our physical capabilities, but our mental ones as well.

The Whole Earth Catalog lists everything from agricultural equipment to books on cybernetics. Now, Brand is witnessing a technology that could tie all these disparate elements together, creating a new kind of community - one built not on shared land, but on shared information.9

Outside the hall, the cool San Francisco night is alive with possibility. The same year that has brought us face to face with humanity's capacity for violence and division - the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy, the war in Vietnam, the global protests - has also shown us its potential for creativity and collaboration.

Engelbart's demo and Brand's Catalog, each in their own way, offer a vision of what might be possible if we harness technology not to replace human intelligence or traditional communities, but to augment and connect them in new ways. Engelbart's demo, like the Earthrise photo soon to be captured by the Apollo 8 crew, offers a new perspective - a vision of what might be possible if we harness technology not to replace human intelligence, but to augment it.

As the crowd disperses into the night, the future remains unwritten. But in this moment, in the convergence of Engelbart's digital dreams and Brand's analog aspirations, a new path forward begins to emerge - one that will shape the development of personal computing, the internet, and our entire digital world for decades to come.

The question that remains, hanging in the air like San Francisco fog, brings us back to a much cited meeting of Douglas Engelbart and the AI pioneer Marvin Minsky. When the two gurus met at MIT in the 1950s, they are reputed to have had the following conversation:10

Minsky: We’re going to make machines intelligent. We are going to make them conscious!

Engelbart: You’re going to do all that for the machines? What are you going to do for the people?

Two From Today

In The New Yorker, Jill Lepore muses on the question: Is a Chat With a Bot a Conversation? while playing with OpenAI’s Advanced Voice Mode.

Interview with Yuval Noah Harari on the podcast Hard Fork, discussing his new book, Nexus - A Brief History of Information Networks from the Stone Age to AI. Like Harari’s previous books (Sapiens, Homo Deus, etc.), so far I’ve found Nexus to be thought-provoking and compelling. But also like his previous work, Nexus is not without critiques and detractors, specifically on how Harari’s methods “may make for deep insights, but it also makes for unsatisfying recommendations.” Yet, the ideas that Harari is presenting feel to me as some of the most urgent and important problems for our culture to consider. I don’t necessarily agree with all he’s saying, but it definitely makes me consider things from a different angle. For example:

Our tendency to summon powers we cannot control stems not from individual psychology but from the unique way our species cooperates in large numbers. The main argument of this book is that humankind gains enormous power by building large networks of cooperation, but the way these networks are built predisposes us to use that power unwisely. Our problem, then, is a network problem.

Even more specifically, it is an information problem. Information is the glue that holds networks together. But for tens of thousands of years, Sapiens built and maintained large networks by inventing and spreading fictions, fantasies, and mass delusions—about gods, about enchanted broomsticks, about AI, and about a great many other things. While each individual human is typically interested in knowing the truth about themselves and the world, large networks bind members and create order by relying on fictions and fantasies. That’s how we got, for example, to Nazism and Stalinism. These were exceptionally powerful networks, held together by exceptionally deluded ideas. As George Orwell famously put it, ignorance is strength.