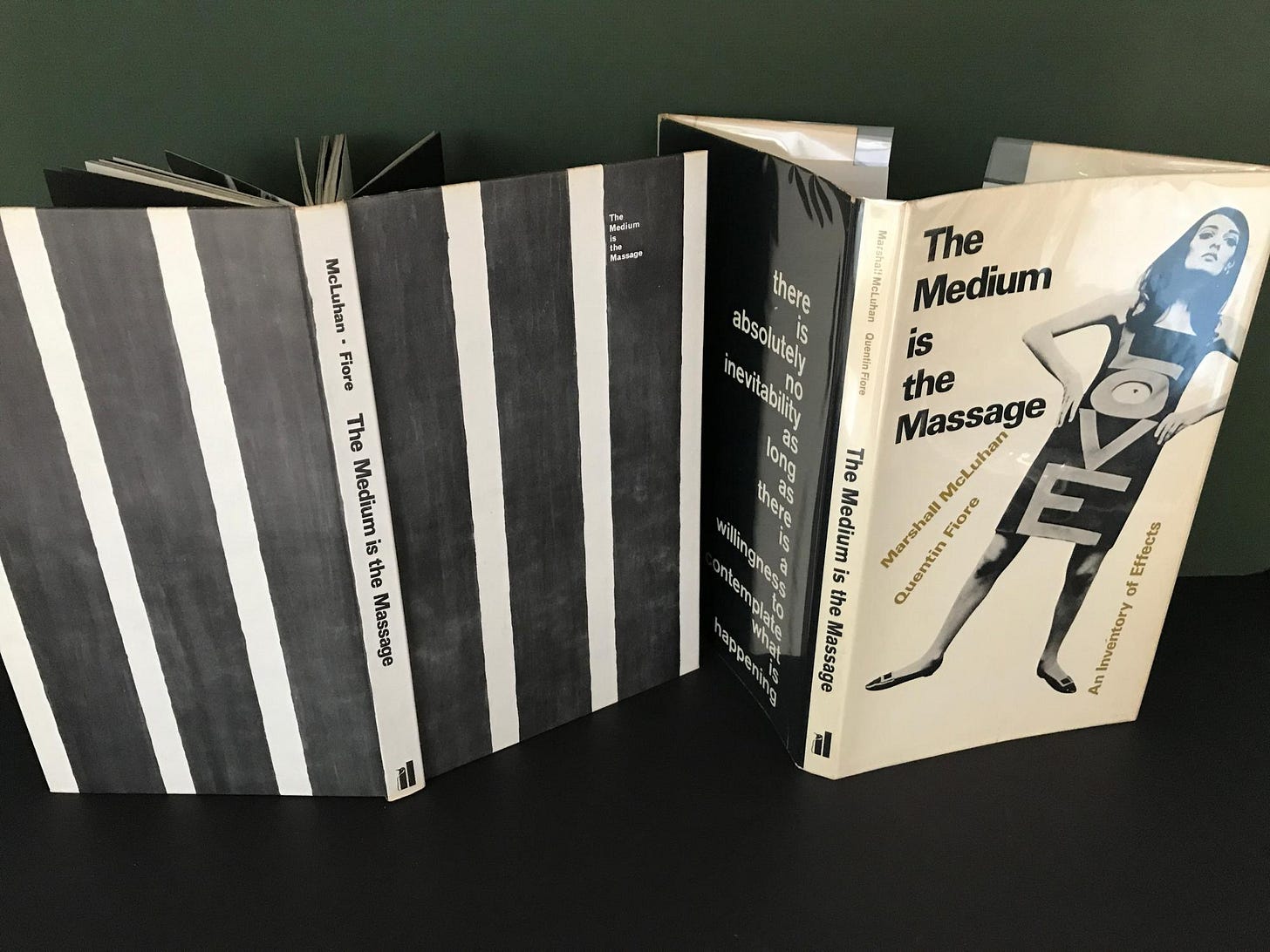

In 1967, as Marshall McLuhan's The Medium is the Massage hit bookstores, the world already embodied his provocative ideas. The book itself was a repackaging of his thoughts from earlier essays,1 including:

“Our conventional response to all media, namely that it is how they are used that counts, is the numb stance of the technological idiot.

For the ‘content’ of a medium is like the juicy piece of meat carried by the burglar to distract the watchdog of the mind.”

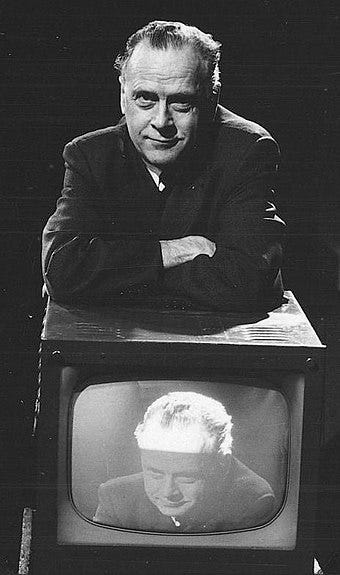

McLuhan, a Canadian philosopher, had once vowed never to become an academic. Yet here he was, a professor of English turned media theorist, his words reshaping how we understood technology and society. It was his first teaching post at the University of Wisconsin that truly set him on his path. Faced with students barely younger than himself, McLuhan felt a generational gulf that he suspected had everything to do with how they learned and perceived the world.

This realization sparked a lifelong investigation into media and its effects, culminating in works like "Understanding Media" in 1964, which he argued that the medium through which we communicate — at the time, this was a combination of television, radio, print, and the telephone — is what fundamentally alters our society and how we think and behave. Therefore, in order to understand social and cultural changes we should be paying more attention to the mediums of communication, rather than the content being communicated The medium was the message — kneading our collective consciousness into new shapes, each technological advance massaging our perception of reality.

But then picture this: A young Jocelyn Bell Burnell, hunched over reams of data from a radio telescope, spots an anomaly. Pulsars: cosmic lighthouses, neutron stars spinning with a precision that would make Swiss watchmakers weep. These celestial bodies, once theoretical figments of quantum physics, now blinked real and insistent. The medium of radio astronomy had massaged our universe, expanding it beyond our wildest dreams.2

Meanwhile, in a Cape Town operating theater, Dr. Christiaan Barnard held a beating heart in his hands, preparing to place it in another human's chest.3 The first successful human heart transplant wasn't just a medical breakthrough; it was a redefinition of life and death. The medium of modern medicine had massaged our very concept of mortality.

But while some hearts were being transplanted, others were being shattered. The Six-Day War erupted in the Middle East, a blitzkrieg that redrew maps and reshaped geopolitics.4 In America, race riots scorched cities, the heat of centuries-old injustices finally boiling over.5 Vietnam protests swelled, their chants of "Hey, hey, LBJ, how many kids did you kill today?" echoing through streets and campuses. The medium of television brought these conflicts into living rooms, massaging public opinion with every broadcast.

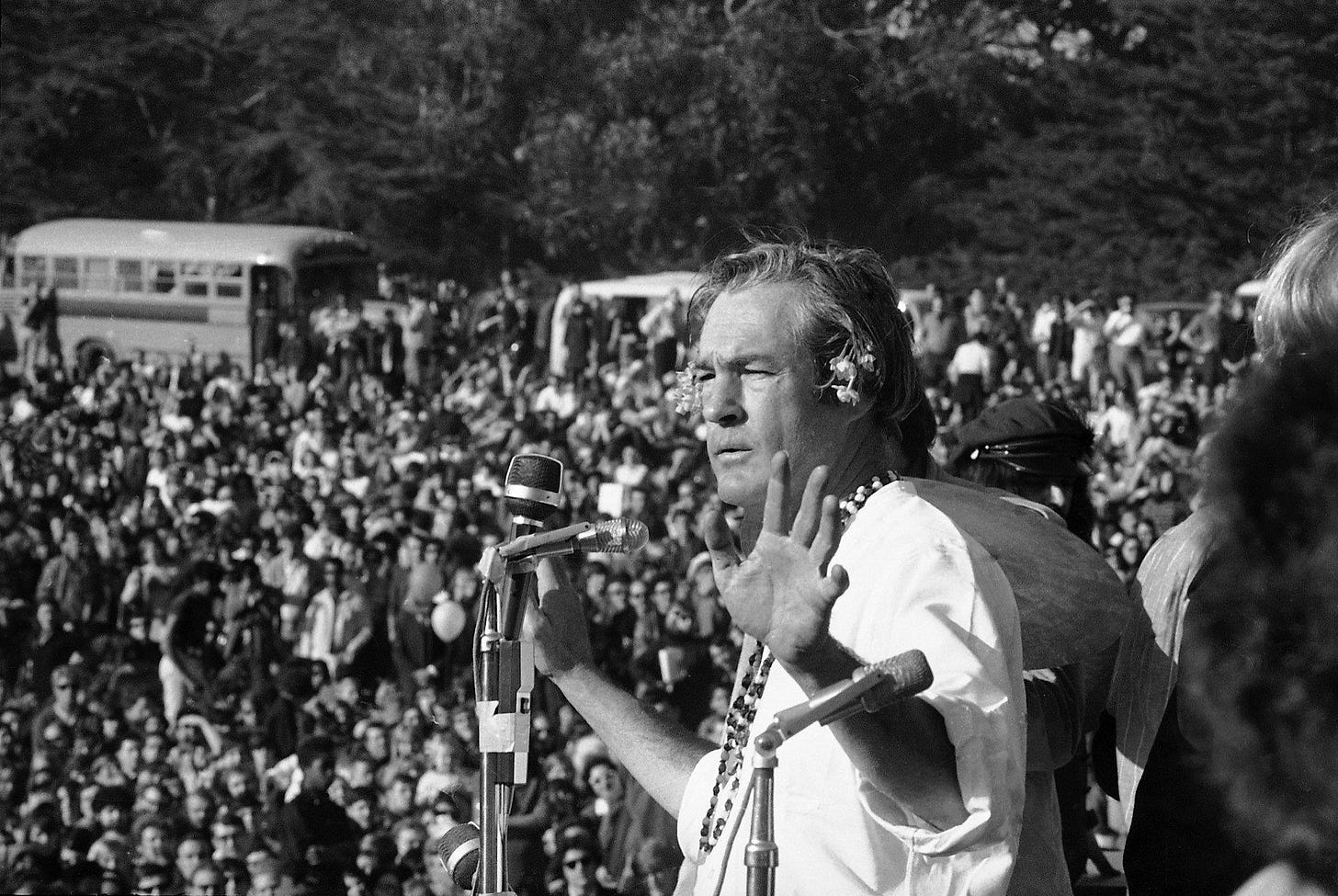

In San Francisco's Golden Gate Park, Timothy Leary urged a crowd of over 30,000 at the Human Be-In to "turn on, tune in, drop out."6 The Summer of Love bloomed in Haight-Ashbury, a psychedelic massage of the American psyche. But for every flower child, there was a soldier in the Mekong Delta, for every peace sign, a clenched fist raised in protest.

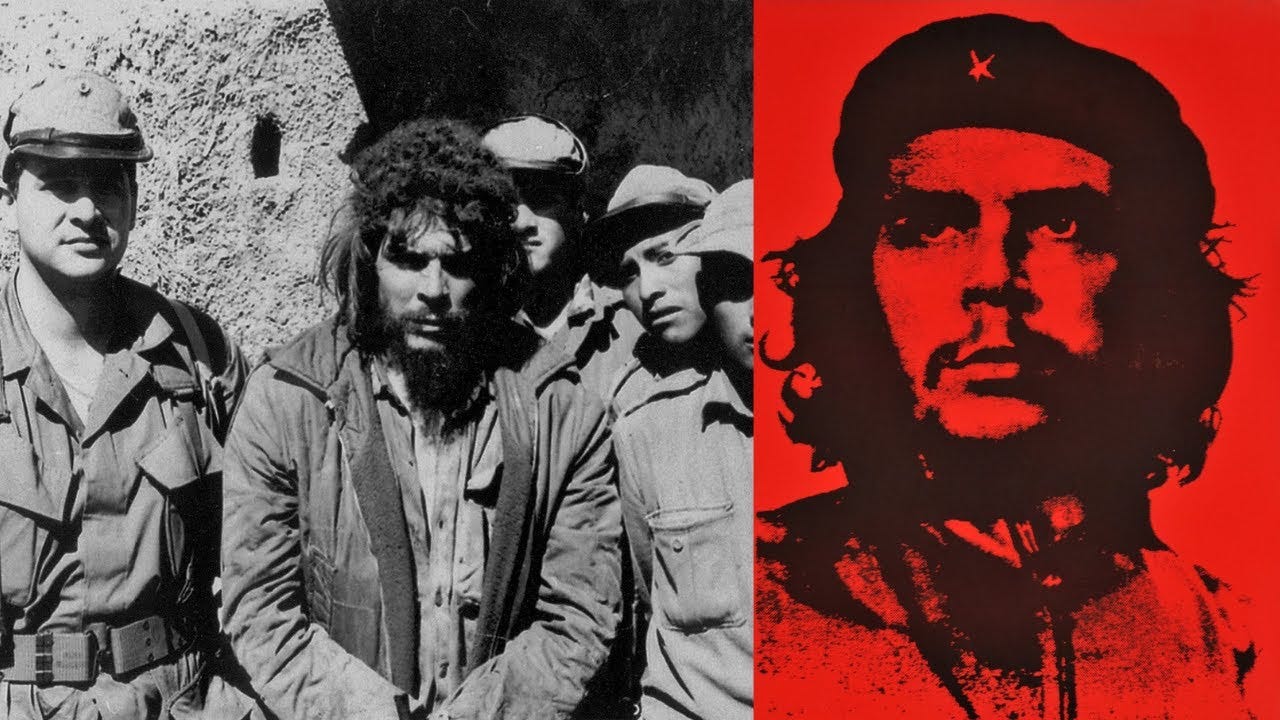

Across the Pacific, Mao's Cultural Revolution continued its frenzied rewriting of Chinese society. Books burned, traditions crumbled, and a nation's history was massaged into a new, revolutionary shape. Meanwhile, in Bolivia, Che Guevara met his end, but even his death would be subject to media manipulation. Moments before his execution, a CIA agent instructed his Bolivian captors to shoot below the neck, staging his death as a battlefield casualty. The truth of his execution would remain hidden for years, a secret preserved in an age of film rather than instant digital exposure. The CIA agent, unable to resist the allure of documenting the moment, took photographs that would remain locked away for two decades. In death, Che's image would be massaged from revolutionary to pop culture icon, his face adorning t-shirts worn by those who'd never read his manifestos, while the real circumstances of his demise lay hidden, awaiting the right medium to bring them to light.7

But amid the tumult, quiet revolutions were brewing in labs and garages across the world. In Gatlinburg, Tennessee, Lawrence Roberts presented the first plans for ARPANET, the prehistoric ancestor of our modern internet.8 They couldn't have known they were laying the groundwork for a medium that would massage global communication into forms McLuhan himself couldn't have imagined.

In a Texas Instruments lab, engineers tinkered with the first handheld calculator, a pocket-sized device set to make the slide rule obsolete.9 The CDC 7600, a behemoth of a supercomputer, hummed to life, its 36 million floating-point operations per second a harbinger of the digital age to come.

At Bell Labs, researchers were threading glass with light, their work on fiber optics promising to rewire the world's communication networks. And in a nondescript living room, Ralph Baer hunched over his "Brown Box," the first home video game console, unknowingly birthing an industry that would massage our entertainment, our social interactions, and even our concept of reality itself.10

Each of these innovations was more than just a new gadget or discovery. They were new mediums, each massaging our world in ways both subtle and profound. The MOSFET transistors being perfected in 1967 would shrink computers from room-sized behemoths to pocket-sized companions. Fiber optics would collapse global distances, making McLuhan's "global village" a tangible reality.

But even as these tangible technologies were reshaping our physical world, other visionaries were quietly laying the groundwork for a revolution in how we process and understand information itself. Just a year earlier, in 1966, Ross Quillian had introduced his Semantic Web and SYNTHEX project, pioneering concepts of network-based knowledge representation. Quillian's work, though less publicized than McLuhan's, was equally prescient. It foreshadowed a world where information would flow not just through physical wires and transistors, but through vast, interconnected webs of meaning and context. This vision aligned perfectly with McLuhan's notion of technology as an extension of human cognition, hinting at a future where the medium wouldn't just massage our external reality, but our very thought processes.

As McLuhan wrote, "Societies have always been shaped more by the nature of the media by which men communicate than by the content of the communication." In 1967, these new media were reshaping society at a dizzying pace. The content - be it war footage from Vietnam, psychedelic rock from San Francisco, or the beeps of a pulsar from deep space - was almost secondary to the transformative power of the mediums themselves.

The year 1967 stood at the cusp of a new era, one where the boundaries between human and machine, between reality and simulation, would increasingly blur. As the world grappled with age-old conflicts and societal upheavals, the seeds of a digital revolution were being sown.

McLuhan's massage was just beginning, and the fingertips of technology were only starting to work their way into the knots of human existence. The real deep tissue massage of the Information Age was yet to come, but 1967 had set the table, laid out the oils, and dimmed the lights. The future was ready for its appointment.