Note:

As we venture into the 1960s, this week I attempt to echo the narrative style of New Journalism—a revolutionary reporting style that emerged over the course of the decade. I’m hoping to capture not just the facts of AI's development, but the feel of the era—its hopes, fears, and contradictions.

Pioneered in the early 60s by writers like Norman Mailer, and Gay Talese, and later synonymous with writers like Tom Wolfe, Joan Didion, Hunter S. Thompson, and Truman Capote, New Journalism blurred the lines between objective reporting and subjective experience, and used literary techniques to create immersive, emotionally resonant storytelling. It profoundly changed how people consumed and interpreted information, challenged traditional notions of objectivity, and in some ways, opened the door to more nuanced explorations of complex topics.

This week we zoom in on an episode of a CBS documentary series called “The Thinking Machine” that was shot at MIT in 1961.1

The Thinking Machine Comes to the Small Screen

The studio lights at MIT blaze, hot and unforgiving.

David Wayne, the actor with a face known to millions, stands facing a camera, its unblinking eye stares back at him. In a voice smooth as polished mahogany, Wayne introduces himself and says:

"As all of you are, I'm concerned with the world in which we're going to live tomorrow. A world in which a new machine, the digital computer, may be of even greater importance than the atomic bomb.”

And then, without barely taking a breath, Wayne asks the question that brought them to the studio that day:

“Can machines really think?”

It is 1961. In Cambridge, Massachusetts, the air crackles with possibility.

Wayne takes his seat in an armchair, legs crossed, a lit cigarette in one hand, wisps of smoke rising. Beside him, Professor Jerome Wiesner, scientist and future presidential advisor, leans forward, his eyes fixed on a screen just out of view. The two men sit facing each other, the cameras rolling, capturing every twitch and gesture. This is television, after all, that hungry beast that devours reality and regurgitates it in neat, digestible chunks for the masses. Wayne turns to Wiesner and says: “What really worries me today is what’s going to happen to us if machines can think? And what interests me specifically is: can they?”

Wiesner pauses, his scientist's certainty wavering. "That's a very hard question to answer," he says, his voice measured, "If you'd asked me that question just a few years ago, I'd have said it was very far-fetched. And today, I just have to admit I don't really know. I suspect if you come back in four or five years, I’ll say, ‘sure, they really do think.’"

The camera crew bustles around them, adjusting lights, checking angles. They are broadcasting to a nation both fascinated and frightened by the prospect of thinking machines.

But outside, beyond the walls of MIT, another America stirs.

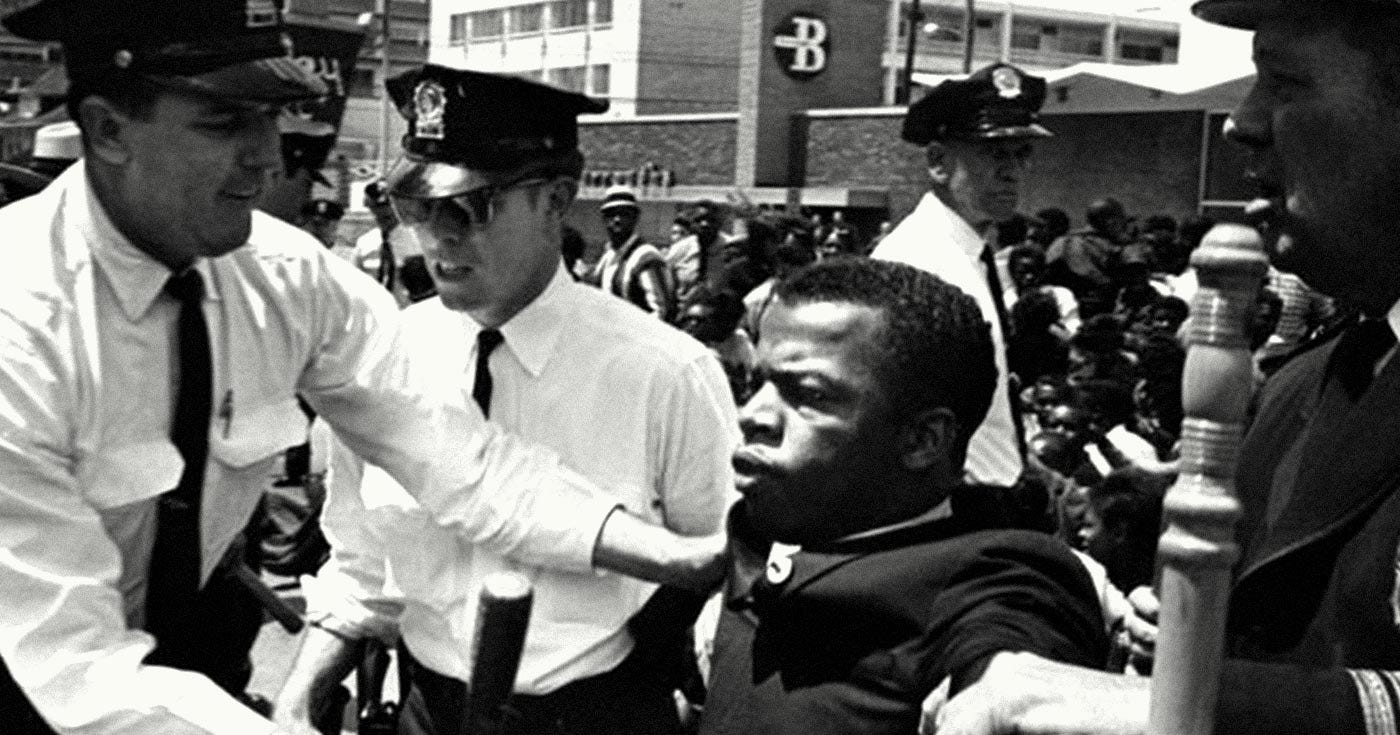

In a bus station in Rock Hill, South Carolina, John Lewis stands, his legs stiff from a long ride. He’s 21 years old, a Freedom Rider. The future, for him, is not about machines that can think, but about the right to be seen as fully human. He takes a deep breath and steps into the "Whites Only" waiting room. History holds its breath.2

Back in the studio, Wayne and Wiesner turn to watch a film clip of a young child learning the alphabet, her small hand tracing wobbly letters on a screen. "W," she says triumphantly, pointing to an M.

Wiesner watches, his eyes thoughtful. "You see, of course, she makes mistakes at first," he explained. "The real question is, how does she ever learn to get them right?"

The scene in front of Wayne and Wiesner shifts. A man in a white coat peers into a microscope, probing the secrets of a frog's vision. "It seems that the frog only sees things that move," Wiesner explains, as Wayne leans in, fascinated.

Perhaps animals can teach us something about thinking and learning? In the race to space, NASA turns its gaze to an unlikely pioneer: the chimpanzee. With response times and internal organs eerily similar to humans, these apes become unwitting astronauts. In sterile rooms reeking of banana pellets and anxiety, forty chimps are conditioned for the cosmos. Meet Ham, or “Number 65,” plucked from the French Cameroons, shuttled to a rare bird farm in Florida, and sold to the U.S. Air Force for a mere $457. An African-born chimpanzee that represents the bridge between Earth and the stars.

The training is a space-age Skinner box: lights flash, buzzers blare, and small hands reach for levers. A correct response within five seconds earns a treat; hesitation or error, a shock to the feet. But it doesn't stop there. These simian pioneers are strapped into centrifuges, bodies wracked by simulated launch forces, and floated in brief arcs of weightlessness. It's a grueling regimen designed to prepare them for a journey to the very edge of Earth's atmosphere—a voyage far beyond anything their evolutionary history could have prepared them for.

Ham emerges as the alpha astronaut, dressed in a nappy, waterproof pants, and a spacesuit. Sealed into the capsule of the 25-metre-long Mercury-Redstone 2 spacecraft, he endures a 16-minute ordeal. Crushing forces assault him on take-off and re-entry, punctuated by more than six minutes of weightlessness. Despite his evident terror, Ham emerges seemingly unharmed, beating Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin—the first human in space—by a clear 10 weeks.3

The simian pioneer paves the way for American astronaut Alan Shepard. After splashdown and recovery, Shepard steps from his Mercury capsule at Cape Canaveral, legs wobbly but smile triumphant. The space above him seems endless, full of promise and challenge—a testament to the sacrifices made by his primate predecessor in humanity's relentless push to the stars.4

Back in Cambridge, Wayne and Wiesner are watching footage of a massive computer, the TX-2, its banks of lights blinking in cryptic patterns. "This enormous collection of wires, tubes, transistors, and circuits connects the largest computer memory now operating," Wiesner explains, his voice tinged with awe.

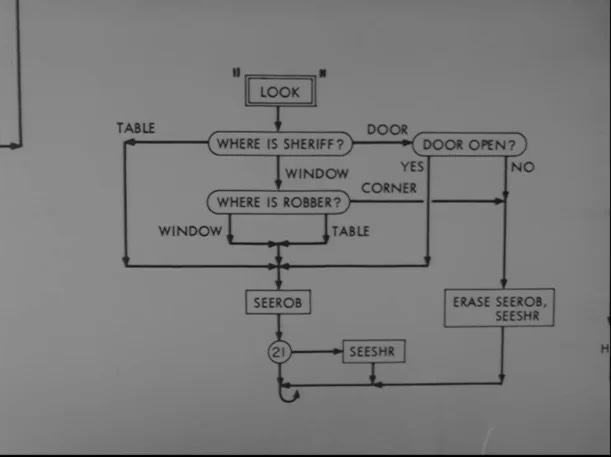

Wayne and Wiesner continue, presenting a dizzying array of experiments and predictions. A computer plays checkers, composes a script for a television Western, solves logic puzzles. With each demonstration, Wayne's expression oscillates between wonder and concern.

In Berlin, the first concrete blocks are being stacked under the cover of darkness, the embryonic stages of what will become a 155-kilometer scar across the city. This wall, rising like a physical manifestation of the Iron Curtain, stands as a stark symbol of the ideological chasm threatening to swallow the world.5

As ninety miles off the coast of Florida, Cuba simmers with tension. The Bay of Pigs fiasco, a CIA-backed invasion attempt barely four months old, has left more than egg on America's face. Its embers still smolder, a stark reminder that even superpowers can stumble spectacularly on the world stage. The failed operation has not only strengthened Castro's grip on power but has pushed Cuba further into the Soviet orbit, setting the stage for a nuclear showdown that will bring the world to the brink of annihilation.6

But in Belgrade, the Non-Aligned Movement seeks to chart an independent course through the Cold War's treacherous waters. Its members, from India to Yugoslavia to Egypt, reject the binary choice between East and West, striving instead for self-determination and a new international economic order. This fledgling alliance stands as a rebuke to imperialism, and aims to “create an independent path in world politics that would not result in member States becoming pawns in the struggles between the major powers.” A reminder that the world is more complex than a simple two-tone map.7

Back in the studio, Claude Shannon appears on screen, the father of information theory, his eyes bright with the fervor of a prophet who has glimpsed the promised land, and he says: “In discussing a problem of simulating the human brain on a computing machine we must carefully distinguish between the accomplishments of the past and what we hope to do in the future. Certainly the accomplishments of the past have been most impressive, we have machines that will translate to some extent from one language to another, machines that will prove mathematical theorems, machines that will play chess or checkers sometimes even better than the men who designed them.”

"I confidently expect," Shannon says, his voice steady, "that within 10 or 15 years, we will find emerging from the laboratories something not too far from the robot of science fiction fame."

"Exciting and challenging," Wayne says to Wiesner as the program nears its end. "But doesn’t it all worry you?"

Wiesner pauses, weighing his words carefully:

“Well sure it worries me, but you know the problems posed by the computer are really no different than the problems we have with other products of technology. It's gonna take a great deal of wisdom on our part to manage them, but if we do, we're going to make a much better world.”

In Anniston, Alabama, a bus carrying Freedom Riders erupts in flames, a firebomb cuts short their journey towards justice. Young men and women, their courage as palpable as the humidity, scatter from the inferno, coughing and stumbling, their eyes stinging from more than just smoke.

As the studio lights dim and the cameras power down, Wayne and Wiesner sit in silence for a moment. Inside these hallowed halls of MIT, you can almost here the whir of machines learning to think, while outside, the world reverberates with the shouts of humans learning to be free. The future hangs in the balance.